SURGICAL ANATOMY STATION OF SALIVARY GLANDS | PAROTID GLAND | SUBMANDIBULAR GLAND

- A 36 years old female comes to your surgical out-door with the complain of progressive enlarging of a painless lump in the front of her neck since 6 months. On examination, mass moves upwards with swallowing. Patient is worried about her looks and asks you questions regarding it.

- In this station of surgical anatomy you will be asked to identify the structures marked on the `prosection’ and related questions about the structures.

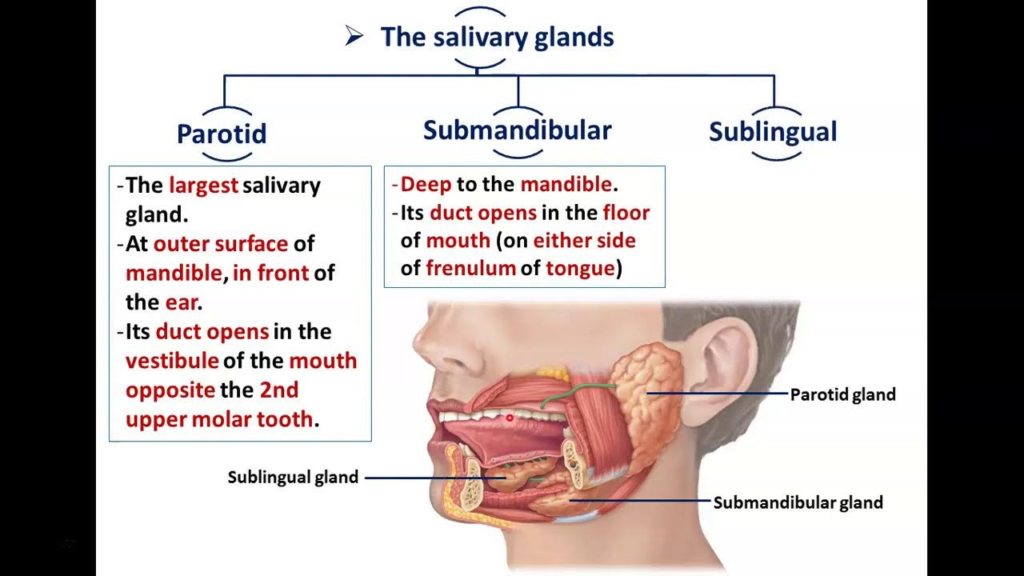

Q.How many salivary glands are there?

There are 3 pairs of major salivary glands and numerous minor salivary glands in the oral cavity:

The 3 pairs of major salivary glands are:

1. Parotid glands: The largest salivary glands located in front of the ears. They secrete serous saliva.

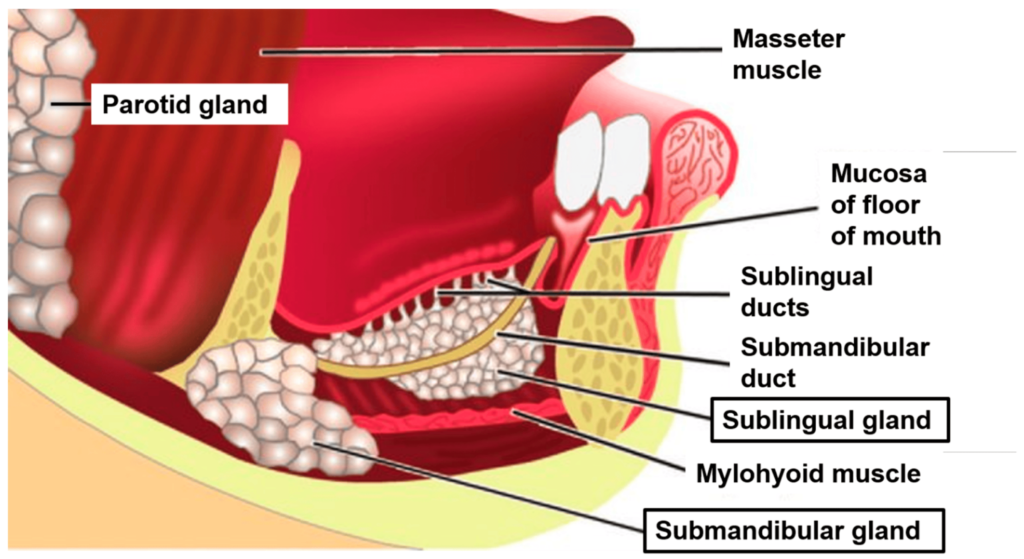

2. Submandibular glands: Located in the floor of the mouth. They secrete both serous and mucous saliva.

3. Sublingual glands: Located in the floor of the mouth beneath the tongue. They secrete mainly mucous saliva.

In addition, there are 600-1000 minor salivary glands located throughout the oral cavity in the lips, cheeks, palate, and tongue. They also secrete mucous or serous saliva.

So the total number of salivary glands includes:

• 2 parotid glands (major)

• 2 submandibular glands (major)

• 2 sublingual glands (major)

• 600-1000 minor salivary glands

• For a total of 604 to 1006 salivary glands in and around the oral cavity.

The saliva secreted from these glands helps keep the oral tissues moist, aids in digestion, protects the teeth and also has antimicrobial properties. Damage or blockage to the salivary glands or their ducts can lead to dry mouth, infections and issues with swallowing and speech.

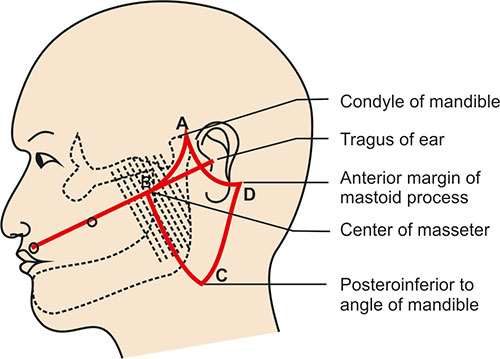

Q.Surface marking of parotid gland ?

– Shape and size: The parotid gland has an irregular shape and is about the size of a walnut. It lies over the ramus of the mandible, in front of the ear.

– Borders:

– Superior border: Extends from the zygomatic arch to the mandibular angle.

– Anterior border: Extends from the mandibular ramus to the parotid duct opening.

– Posterior border: Extends from the mastoid process to the mandibular angle.

– Parotid duct: Emerges from the anterior border and crosses the masseter muscle. Opens at the level of the upper 2nd molar tooth, midway between the tragus and nose.

– Facial nerve: Emerges from the lower border, 2.5 cm in front of the ear. Runs downwards and forwards over the parotid gland.

– External jugular vein: Crosses superficial to the posterior half of the parotid gland. Formed by posterior auricular vein and posterior retromandibular vein behind the gland.

– Great auricular nerve: Provides sensory innervation to the parotid gland. Emerges behind the mandibular angle and runs upwards over the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

– Relations: The parotid gland overlies the ramus of the mandible and mastoid process of the temporal bone. It is embedded within the deep cervical fascia. The facial nerve and external carotid artery course through the gland.

– Parotid gland movement: Moves posteriorly when mouth opens due to its relation to the masseter muscle and mandible. It contracts and secretes saliva during feeding and swallowing.

– To examine the parotid gland: Place your fingers over the ramus of the mandible in front of the ear. Push upwards and backwards as the patient clenches their jaws and then relaxes. You may feel the parotid gland enlarge during contraction and its surface should be smooth. Compare both sides.

The parotid gland is the largest of the three pairs of salivary glands. Its surface markings are:

1. It lies over the ramus of the mandible, in front of the ear. The gland extends from the zygomatic arch above to below the angle of the mandible.

2. The parotid duct (Stensen’s duct) emerges from the anterior border of the gland and crosses over the masseter muscle. It then turns medially to open into the buccal cavity at the level of the upper second molar tooth.

3. The surface marking of the parotid duct corresponds to a line drawn downwards from the tragus of the ear to midway between the upper lip and nose. The duct lies roughly midway along this line.

4. The facial nerve (CN VII) emerges from the lower border of the parotid gland, about 2.5 cm in front of the ear. The main trunk of the facial nerve runs downwards and forwards over the body of the parotid.

5. The external jugular vein crosses superficial to the parotid gland. It is formed posterior to the gland by the union of the posterior auricular vein and posterior division of the retromandibular vein.

6. The great auricular nerve provides sensory innervation to the skin and parotid gland. It emerges from the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and runs upwards over the sterno-mastoid and behind the angle of the mandible.

7. The parotid gland moves posteriorly when the mouth opens. During feeding and swallowing, it contracts and secretes saliva through the parotid duct.

The parotid gland and its related structures (duct, facial nerve, external jugular vein, great auricular nerve) can be examined clinically by inspection and palpation using the surface markings as a guide.

The parotid gland has the following main parts:

1. Superficial lobe: The larger, posterior part of the gland. It overlies the ramus of the mandible and mastoid process.

2. Deep lobe: The smaller, anterior part that extends into the cheek. It passes medial to the ramus of the mandible. The parotid duct emerges from the deep lobe to open into the buccal cavity.

3. Parotid capsule: A fibrous capsule that encloses the gland. It is thick posteriorly but thin anteriorly where it splits to enclose the parotid duct. The capsule is attached to the mandible and mastoid process.

4. Facial nerve (CN VII): Passes through the deep lobe, closer to the posterior border. It emerges from the lower part of the gland about 2.5 cm in front of the ear. The main trunk runs downwards and forwards on the superficial surface of the gland.Damage to the facial nerve during parotid gland surgery can cause paralysis of the muscles of facial expression.

5. External carotid artery: Gives off the posterior auricular branch which supplies the posterior part of the gland. The retromandibular vein accompanies the external carotid artery through the deep lobe.

6. Parotid duct (Stensen’s duct): About 7 cm long. Passes from the deep lobe, pierces the buccinator muscle to open into the buccal cavity opposite the upper 2nd molar tooth.The duct emerges from the anterior border of the gland, and is enclosed by a split in the parotid capsule.

7. Parotid lymph nodes: 10-20 lymph nodes embedded within the parotid gland that help filter lymph draining the face, cheeks, nose, mouth and pharynx.

8. Parasympathetic innervation: Via the auriculotemporal nerve. It stimulates secretion of watery saliva from the parotid gland.

9. Sensory innervation: Via the great auricular nerve. It provides sensation to the skin over the parotid gland and the anterior external ear.

10. Blood supply: Branches from the external carotid artery including superior thyroid, posterior auricular, superficial temporal and transverse facial arteries. Venous drainage is into the retromandibular vein.

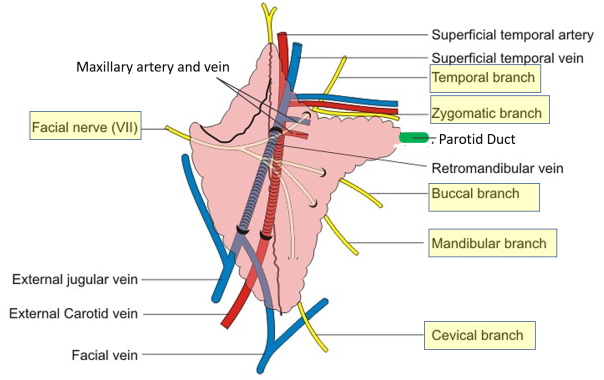

Q. important structures pass through the parotid gland?

Here are the structures passing through the parotid gland ordered from superficial to deep and medial to lateral:

Superficial to deep:

1. Great auricular nerve

2. Parotid duct (Stensen’s duct)

3. Facial nerve (CN VII)

4. External carotid artery and retromandibular vein

5. Parotid lymph nodes

6. Auriculotemporal nerve

Medial to lateral:

1. Parotid duct (Stensen’s duct): Originates from the deep lobe medially, passes laterally to open into the buccal cavity.

2. Facial nerve (CN VII): Passes through the deep lobe of the parotid gland medially, closer to its posterior border. Emerges laterally about 2.5 cm in front of the ear.

3. External carotid artery: Gives branches medially supplying the deep lobe of the gland. Passes laterally through the parotid gland.

4. Retromandibular vein: Accompanies the external carotid artery, passing medially to laterally through the deep lobe of the parotid gland.

5. Parotid lymph nodes: Distributed throughout the parotid gland, likely more medially in the deep lobe.

6. Auriculotemporal nerve: Provides parasympathetic secretomotor innervation medially in the deep lobe of the parotid gland. Continues laterally to supply other structures.

7. Great auricular nerve: Emerges medially behind the mandibular angle, passes laterally over the parotid gland to supply the skin and parotid gland capsule.

The parotid gland secretes serous saliva, which is:

• Watery and thin: Contains over 99% water with some enzymes, electrolytes and antibodies. Serous saliva has a watery consistency compared to the thicker mucous saliva secreted by the submandibular and sublingual glands.

• Secreted in large amounts: The parotid glands produce 60-65% of the total saliva in the mouth at rest. This increases to 80% during stimulation or mastication. The voluminous secretion is due to the gland’s large size and number of acini.

• Important for digestion: The serous saliva secreted by the parotid glands contains the digestive enzyme alpha-amylase which helps break down starches in the mouth. It also helps moisten and lubricate food for swallowing.

• Important for oral health: The parotid glands secrete salivary immunoglobulins like IgA which help prevent adhesion of bacteria to teeth and oral tissues. Saliva also helps wash away food particles and keeps the mouth moist, preventing dry mouth.

• Controlled by parasympathetic stimulation: Secretomotor innervation of the parotid glands is via the auriculotemporal nerve. Acetylcholine stimulates the secretion of copious, watery saliva.

• Reflexively stimulated: The sight, smell and taste of food can reflexively stimulate the parotid glands to increase saliva secretion in anticipation of eating. This is known as the cephalic phase of digestion.

• Composition: The main constituents of parotid saliva include:

› Water (>99%): Gives saliva a thin, watery consistency.

› Alpha-amylase: A digestive enzyme that breaks down starch.

› Electrolytes: Primarily sodium, potassium, bicarbonate and chloride ions. Maintain pH and osmolarity.

› Antimicrobial agents: Include lysozyme, lactoferrin, IgA and others which provide protection.

› Miscellaneous: Include glucose, urea, nitrogenous products.

Q. differential diagnosis?

A swelling or lump in the parotid region can have several possible differential diagnoses:

1. Parotid gland tumor: The most common cause. Can be benign (pleomorphic adenoma) or malignant (mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenocarcinoma). Usually slow growing, firm and non-tender.

2. Parotitis: Inflammation or infection of the parotid gland. Can be acute or chronic. Swelling may be tender, erythematous and often accompanied by fever or purulent discharge from parotid duct.

3. Benign lymphoepithelial lesion: Due to inflammation and enlargement of parotid lymph nodes. Seen in HIV infection or congenital immunodeficiencies. Swelling is diffuse, bilateral and non-tender.

4. Calculus or sialolithiasis: Stone obstruction of the parotid duct leading to swelling and tenderness in the gland or duct region. May cause pain, especially during salivary stimulation. Usually unilateral and resolves once stone is removed or passed.

5. Adenitis: Swelling of the parotid lymph nodes due to local or systemic infection. Tender and often accompanied by fever or sore throat. Will reduce once infection is treated. Diffuse, can be bilateral.

6. Facial nerve schwannoma: Rare, benign tumor of Schwann cells surrounding the facial nerve within the parotid gland. Causes gradual swelling and possible facial weakness or paralysis if enlarged.

7. Lipoma or parotid duct cyst: Uncommon benign growths arising from parotid tissue or duct epithelium. Fluctuant, slow growing and non-tender.

8. Mumps: Acute viral parotitis due to paramyxovirus infection. Causes very painful, tender swelling of one or both parotid glands. Often seen in children. Accompanied by fever, malaise and pain on swallowing. Self-limiting but can lead to complications.

9. Allergic reaction: Rapid parotid swelling due to allergic reaction as histamine release causes edema. Usually accompanied by other signs of allergy such as rash, nasal congestion, etc. Antihistamines and corticosteroids help reduce swelling.

Q. Classify parotid swellings?

1. Benign vs malignant:

– Benign: Pleomorphic adenoma, lipoma, benign lymphoepithelial lesion, sialolithiasis or calculus, adenitis, parotitis.

– Malignant: Mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, facial nerve schwannoma (though usually non-malignant)

2. Neoplastic vs non-neoplastic:

– Neoplastic: Parotid tumors (benign or malignant), facial nerve schwannoma.

– Non-neoplastic: Parotitis (infection/inflammation), sialolithiasis (stone), adenitis (infection of lymph nodes), allergic reaction.

3. Primary vs secondary:

– Primary: Arises from parotid gland tissue e.g. pleomorphic adenoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

– Secondary: Due to pathology outside the parotid gland e.g. metastatic tumor spread to parotid nodes, lymphoma of parotid nodes, swollen nodes due to local/systemic infection (adenitis), HIV infection (BLL).

4. Unilateral vs bilateral:

– Unilateral: Most parotid tumors (benign and malignant), sialolithiasis, acute parotitis.

– Bilateral: Chronic parotitis, benign lymphoepithelial lesion, mumps, allergic reaction.

5. Sudden vs gradual onset:

– Sudden onset: Mumps, acute parotitis, acute allergic reaction (hours to days).

– Gradual onset: Most tumors (weeks to months), chronic parotitis, BLL (months to years).

6. Hard vs soft consistency:

– Hard: Majority of parotid tumors.

– Soft/fluctuant: Parotitis (especially with abscess), sialolithiasis (if fluctuant), allergic reaction, mumps.

7. Painful vs painless:

– Painful: Parotitis (especially acute), sialolithiasis, adenitis, allergic reaction, mumps.

– Painless: Most parotid tumors (unless large/invasive), BLL.

Q. what are parotid infections?

Parotid infections can present as:

1. Acute parotitis:

• Sudden painful swelling of one or both parotid glands due to bacterial infection. Common causative bacteria include Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus viridans and anaerobes like Bacteroides.

• Usually unilateral. Can be accompanied by fever, chills, purulence from parotid duct, tenderness and erythema over the gland.

• More common in debilitated or dehydrated elderly patients. Also seen in HIV infection, diabetes or during hyperalimentation therapy.

• Requires oral antibiotics e.g. amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and frequent warm saline irrigations of parotid duct. Hospitalization may be needed for severe cases.

2. Chronic parotitis:

• Recurrent or persistent inflammation of one or both parotid glands lasting months to years. Exact cause is not well known but may involve genetic, immunologic, bacterial or lifestyle factors. Not usually due to infection.

• May lead to abscess formation, sialolithiasis or scar tissue preventing salivary outflow causing pain and swelling during meals. Damage to gland tissue over time causes derangement in saliva secretion.

• Treatment involves managing exacerbations, promoting salivary flow, duct massage and preventing recurrence. Some cases may require surgical resection of damaged gland tissue.

3. Tuberculosis of parotid gland:

• Rare form of tuberculosis infection that involves the parotid glands. Presents as slow growing, painless mass or masses in the parotid region. Fever, night sweats and weight loss may occur.

• More common in immunosuppressed individuals or those from endemic areas. Requires chest X-ray to rule out pulmonary TB and FNA or culture of parotid mass/nodes to confirm diagnosis.

• Treatment includes long course of anti-TB medications (isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide) to avoid complications like facial nerve palsy. Surgery usually not required.

4. HIV-associated benign lymphoepithelial lesion:

• Due to enlargement of parotid lymph nodes from chronic inflammation in HIV patients. Bilateral, cystic swelling of parotid glands.

• Composed of hyperplastic lymphoid tissue with poor immune function. Despite ‘benign’ terminology, can progress to lymphoma if left untreated.

• Requires ART (antiretroviral therapy) to boost immunity which helps resolve majority of cases. Persistent or non-responsive swellings may need surgical removal.

Q.classification of parotid gland disorders based on pathology:?

1. Infections:

– Acute parotitis: Bacterial infection causing sudden painful swelling.

– Chronic parotitis: Recurrent inflammation, may lead to abscess or sialolithiasis.

– TB parotitis: Rare TB infection causing painless parotid mass. Affects immunosuppressed individuals.

– HIV-associated BLL: Due to chronic inflammation and parotid lymph node enlargement in HIV patients.

2. Benign neoplasms:

– Pleomorphic adenoma: Most common parotid tumor. Slow growing, painless, movable mass.

– Warthin’s tumor: Second most common. Papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum. Painless mass in older males.

– Oncocytoma: Benign tumor of oncocytes (epithelial cells). Salivary gland counterpart of chromophobe adenoma.

– Hemangioma: Benign vascular tumor. Soft, compressible, painless mass that may blanch on pressure.

3. Malignant neoplasms:

– Mucoepidermoid carcinoma: Most common malignant tumor. Painless mass with occasional facial nerve palsy.

– Adenoid cystic carcinoma: Often perineural invasion causing pain. Solid, painful mass.

– Acinic cell carcinoma: Malignant tumor of acini. Firm, solitary mass often with metastases to lymph nodes.

– Lymphoma: Occurs in parotid lymph nodes. May be part of systemic lymphoma or isolated gland involvement.

– Squamous cell carcinoma: Rare, aggressive tumor arising from squamous metaplasia in salivary ducts or from ectopic salivary gland tissue. Painful mass with skin ulceration and fixation.

4. Autoimmune/inflammatory disorders:

– Sjogren’s syndrome: Chronic autoimmune disease damaging salivary and lacrimal glands. Causes dry mouth and dry eyes.

– Sarcoidosis: Multisystem inflammatory disorder that can affect major salivary glands causing swelling, dry mouth, dysphagia.

– IgG4-related disease: Autoimmune disease that can involve parotid glands. Elevated IgG4 levels, multiple organ involvement. Responds to steroids.

5. Others:

– Sialolithiasis: Stone formation in salivary duct causing obstruction, pain, swelling and infection.

– Facial nerve schwannoma: Benign nerve sheath tumor that can arise from parotid portion of facial nerve. Slow growing painless mass causing facial palsy.

– Necrotizing sialometaplasia: Benign, self-limited inflammatory/ischemic disorder of salivary gland tissue. Causes parotid gland swelling and may develop sinus tracts before resolving spontaneously.

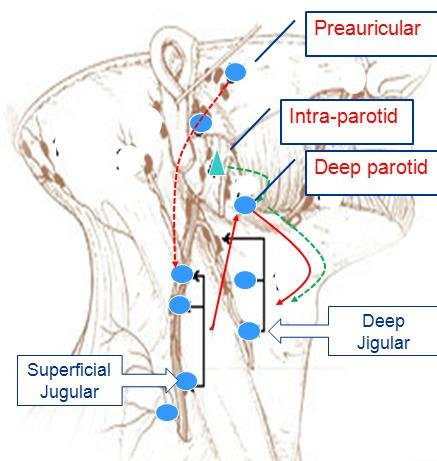

The parotid gland has an extensive lymphatic drainage. The lymphatic vessels from the parotid gland drain into the following lymph node groups:

1. Parotid lymph nodes: There are 10 to 20 lymph nodes embedded within the parotid gland tissue itself. They receive lymph from the parotid gland and its draining regions like the face, cheeks, nose, mouth and pharynx. Enlargement of parotid lymph nodes can lead to swelling visible as a mass near or within the parotid gland.

2. Jugulodigastric lymph nodes: Located along the lower border of the posterior belly of digastric muscle, near the angle of the mandible. They receive lymph from the parotid gland, mandible, lower cheeks and upper neck.

3. Cervical lymph nodes: Deep and superficial cervical lymph nodes in levels I, II and III receive lymph drainage from the parotid gland and adjacent head and neck structures. Enlargement of cervical nodes may be due to pathology within the parotid gland or infection/tumors in the overlying face and neck.

4. Submandibular lymph nodes: Located along the lower border of the mandible, in the submandibular triangle. They receive lymph from the parotid gland, lower cheeks, jaws, gums, anterior tongue and floor of the mouth. swellings in this node group may indicate pathology in the midface, jaws or salivary glands.

5. Retropharyngeal lymph nodes: Located within the retropharyngeal space, behind the pharynx. They receive lymph from the nose, paranasal sinuses, eustachian tubes, middle ear, posterior oral cavity, parotid glands and pharynx. Swelling may indicate infection or tumors in these areas.

6. Deep cervical lymph nodes: Located along the internal jugular vein in the neck. They receive lymph from most of the head and neck region including the parotid gland, nasal cavity, oral cavity, larynx, tonsils, tongue, thyroid, etc. Enlargement often indicates significant pathology that requires further investigation.

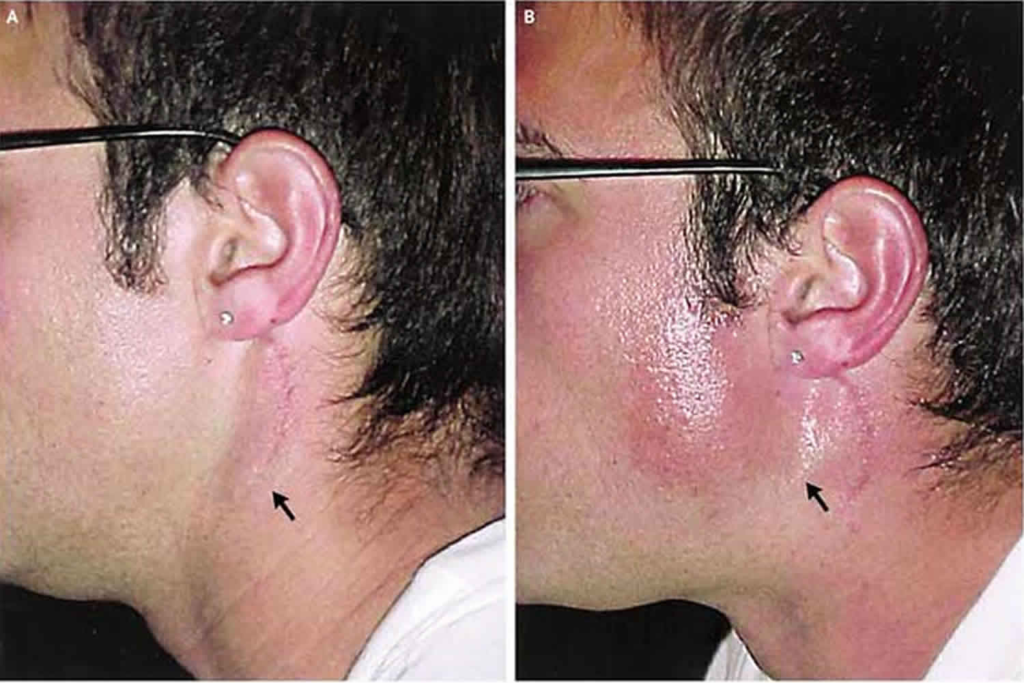

Q.freys syndrome?

Frey’s syndrome, also known as auriculotemporal syndrome or gustatory sweating, is a disorder characterized by sweating in the area of the parotid gland during eating. It occurs due to damage or interruption of the auriculotemporal nerve which carries parasympathetic innervation to the parotid gland. The key features of Frey’s syndrome include:

1. Unilateral sweating: Excessive sweating is usually confined to the area overlying one parotid gland, typically the one that has been operated or traumatized previously. The sweating only occurs on the affected side.

2. Occurs during meals: The sweating episodes are triggered by chewing or salivation during eating, rarely at other times. It reflects aberrant stimulation of parotid gland secretomotor fibers that also supply cutaneous sweat glands.

3. Heat and redness: The affected area may become warm, flushed and erythematous due to vasodilation during the sweating episodes.

4. Stinging or tingling: Some individuals experience stinging, tingling or a crawling sensation in the skin over the parotid gland at the time of gustatory sweating.

5. History of parotid gland trauma or surgery: Frey’s syndrome most often develops following parotid gland surgery (parotidectomy), injury or inflammation where the auriculotemporal nerve is damaged or severed. The nerve then regrows and connects to sweat glands, stimulating them during salivation.

6. Minor’s starch iodine test: Sweating during eating in the parotid area can be confirmed using this test where iodine solution and starch powder are applied to the skin. The iodine turns dark blue when it comes in contact with sweat, clearly outlining the affected area.

7. Treatment: Options include topical aluminum salts to block sweat production, botulinum toxin injections which inhibit acetylcholine release to sweat glands, auriculotemporal nerve excision or rerouting and superficial parotidectomy to remove residual parotid tissue stimulating the nerve.

Frey’s syndrome can develop months to years after parotid gland trauma or surgery and causes distressing sweating and symptoms during eating. Diagnosis is based on characteristic signs and symptoms, with minor’s starch iodine test and history of parotid damage helping to confirm the diagnosis. Various treatment options are available to manage symptoms.

Frey’s syndrome develops due to damage or injury to the auriculotemporal nerve which carries parasympathetic innervation to the parotid gland. The key steps in the development of Frey’s syndrome are:

1. Damage to auriculotemporal nerve: This can occur due to parotid gland surgery (parotidectomy), trauma, inflammation or other procedures in the area. The auriculotemporal nerve may be severed, contused or inflamed, interrupting its parasympathetic fibers.

2. Degeneration of postganglionic parasympathetic fibers: The damaged parasympathetic secretomotor fibers that stimulate the parotid gland degenerate distal to the lesion. This removes parasympathetic stimulation to the parotid gland.

3. Nerve regeneration: After injury, the proximal end of the severed auriculotemporal nerve regenerates and sprouts new nerve fibers. These fibers grow in a disorganized fashion.

4. Aberrant reinnervation: Some of the regenerating parasympathetic fibers wrongly reinnervate nearby sweat glands instead of the parotid gland. This results in a “crossed connection” where the sweat glands are now stimulated by parasympathetic activity meant for the parotid gland.

5. Gustatory sweating: During salivation or eating, the aberrant parasympathetic fibers are activated, stimulating the wrongly reinnervated sweat glands. This results in sweating over the parotid area in response to gustatory stimulation, known as Frey’s syndrome.

6. Vasodilation: In some cases, sympathetic vasodilator fibers may also be stimulated, leading to warmth and flushing over the parotid region during gustatory sweating episodes.

7. Time course: Frey’s syndrome usually develops between 3 months to 2 years following damage to the auriculotemporal nerve due to the time required for nerve degeneration, regeneration and reinnervation of sweat glands. In rare cases, it may appear sooner or later.

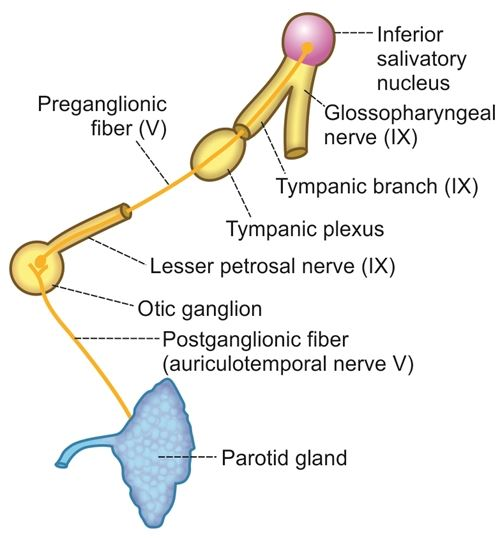

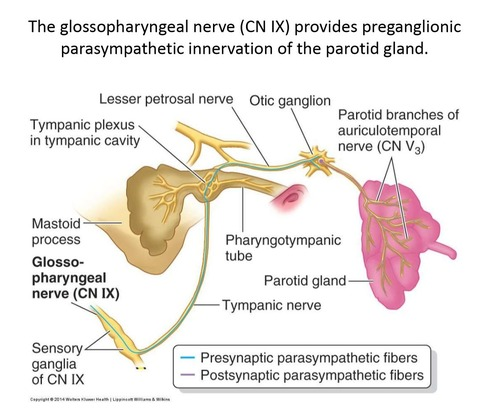

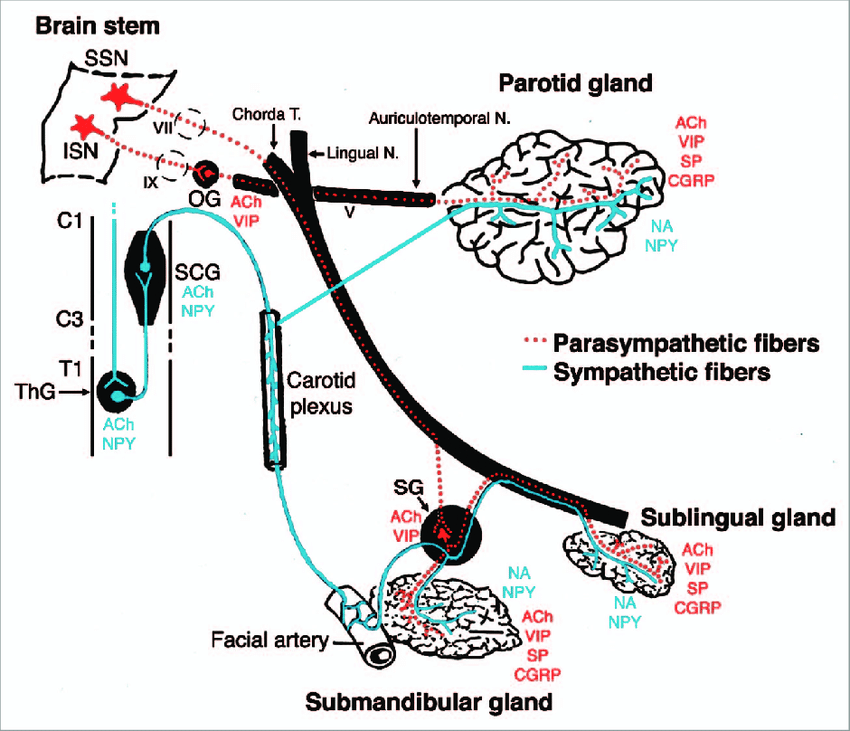

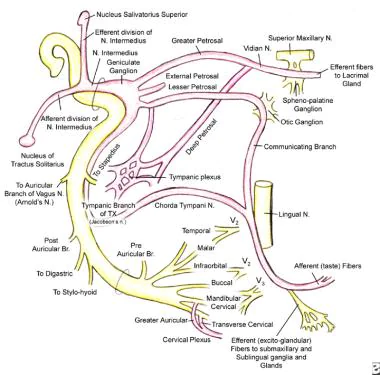

The parasympathetic innervation to the salivary glands originates from the salivatory nuclei in the brainstem, specifically:

1. Superior salivatory nucleus: Provides parasympathetic fibers to the lacrimal gland and submandibular ganglion.

2. Inferior salivatory nucleus: Provides parasympathetic fibers to the parotid gland and otic ganglion.

The preganglionic parasympathetic fibers from these salivatory nuclei synapse in ganglia located close to the salivary glands:

1. Submandibular ganglion: Supplies the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands. Located on the hyoglossus muscle, below the posterior end of the mylohyoid muscle.

2. Otic ganglion: Supplies the parotid gland. Located just below the foramen ovale, medial to the mandibular nerve.

3. Pterygopalatine ganglion: Although not directly involved in salivary gland innervation, some of its postganglionic fibers pass through and carry secretomotor fibers to the lacrimal gland. Located in the pterygopalatine fossa.

The postganglionic parasympathetic fibers from these ganglia provide secretomotor innervation to their target salivary glands as follows:

– Parotid gland: Auriculotemporal nerve (branch of mandibular nerve)

– Submandibular gland: Submandibular ganglion → submandibular glandular branches

– Sublingual gland: Submandibular ganglion → sublingual glandular branches

– Lacrimal gland: Zygomatic nerve (also from maxillary nerve) → lacrimal glandular branches

On stimulation, the parasympathetic fibers release acetylcholine which acts on muscarinic receptors in the salivary glands, stimulating copious watery saliva secretion. Damage or interruption to the parasympathetic innervation of salivary glands can reduce saliva production, causing dry mouth. In the case of the parotid gland, it may also lead to Frey’s syndrome.

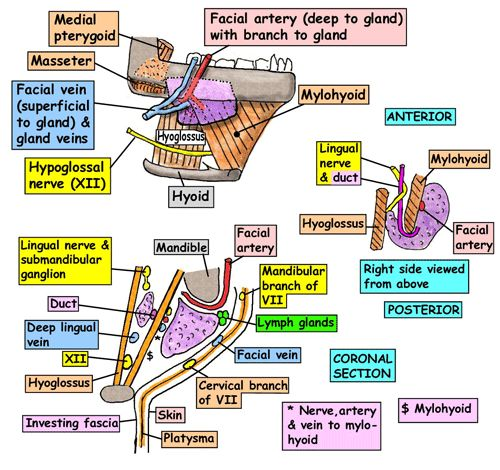

The submandibular gland is one of the major salivary glands located in the submandibular triangle of the neck. Key points about the submandibular gland:

1. Location: Lies partly under the mandible in the submandibular triangle. Wraps around the posterior free border of the mylohyoid muscle.

2. Size and shape: Larger than the sublingual gland but smaller than the parotid gland. Yellowish, irregular in shape.

3. Histology: Contains both serous acini and mucous acini and ducts. Secretes a mixed saliva that is more viscous than parotid saliva but less dense than sublingual saliva.

4. Submandibular duct: About 5 cm long. Emerges from the medial side of the gland, opens at the sublingual papilla beside the lingual frenum. Receives secretions from the sublingual gland.

5. Innervation: Facial nerve → submandibular ganglion → submandibular branches. Parasympathetic fibers stimulate watery saliva. Lingual nerve carries sympathetic fibers which activate mucous saliva.

6. Blood supply: Facial and lingual arteries. Forms anastomosis with submental and sublingual branches.

7. Relations:

– Deep/medial: Mylohyoid muscle, hyoglossus muscle, submandibular lymph nodes.

– Superficial: Skin and superficial fascia, cervical branch of facial nerve, transverse cervical branch of facial vein.

– Posterior: Facial artery and posterior facial vein.

– Anterior: Mylohyoid muscle, submandibular duct (along superior border).

8. Stones: Submandibular gland stones (sialolithiasis) are common due to higher viscosity and alkalinity of saliva. Obstruct submandibular duct causing pain and swelling during salivation. Excision or extraoral lithotripsy may be needed.

9. Other disorders: Infection (sialadenitis), xerostomia (dry mouth), Mucoepidermoid carcinoma, etc.

The submandibular gland secretes both serous and mucous saliva which aids in digestion and lubrication. It is located beneath the mandible, wrapped around the free border of the mylohyoid muscle. The submandibular duct emerges from the gland to open in the mouth.

Q. removal of submandibular gland?

The submandibular gland can be removed surgically through an incision in the submandibular triangle of the neck. The key steps for submandibular gland excision are:

1. Patient positioning: The patient is placed in a supine position with the head turned to the opposite side. A shoulder roll is placed to extend the neck.

2. Incision: A 5 to 6 cm incision is made 2 cm below and parallel to the inferior border of the mandible, centered over the gland. The incision is made through skin, fascia and platysma muscle.

3. Exposure of gland: The facial vein and mandibular branches of the facial nerve are identified and preserved. The marginal mandibular branch is pulled upwards. The floor of the mouth is depressed with a retractor to push the mylohyoid muscle downwards and expose the gland.

4. Isolate and ligate duct: The submandibular duct is identified, isolated and ligated close to the gland to prevent saliva leak. The lingual nerve is preserved.

5. Mobilize the gland: A small cuff of fat and fascia around the gland is kept intact. The gland is gently pushed off the mylohyoid muscle and hyoglossus muscle using a gauze pad. The posterior facial vein is ligated.

6. Remove gland: The gland is suspended with a silk suture to facilitate removal. It is gently eased out of the wound, ensuring no fragments are left behind. The wound is irrigated. A suction drain may be placed.

7. Closure: The platysma muscle is sutured using 3-0 or 4-0 vicryl sutures. Subcutaneous tissue is closed with 4-0 or 5-0 vicryl sutures. Skin is closed with 5-0 nylon or prolene sutures. Adhesive strips and dressing are applied.

8. Post-op care: Drain usually removed after 24-48 hours. Pressure dressing for 2-3 days. Sutures removed after 5-7 days. Oral intake and exercises start soon after surgery based on surgeon preference. Patient is advised not to use straws or make sucking motions to avoid saliva leak from gland excision site.

Complications include temporary or permanent nerve palsy (marginal mandibular branch), salivary fistula, hematoma, wound infection, etc. Submandibular gland excision may be required to treat stones, chronic infections, autoimmune disease or tumors of the gland.

The main nerves at risk during submandibular gland excision are:

1. Marginal mandibular branch of facial nerve: This is the most commonly damaged nerve during submandibular gland surgery. It emerges at the lower border of the mandible and supplies the muscles of the lower lip and chin (depressor anguli oris, depressor labii inferioris).

Damage to this nerve results in unilateral paralysis of the lower lip causing asymmetry of the mouth on smiling or lip movement. Recovery depends on whether the nerve is severed or only bruised. Complete transection is less likely to recover and may need nerve grafting. Partial damage has a better prognosis with recovery in 4 to 8 weeks.

2. Lingual nerve: Provides sensory innervation to the tongue, floor of mouth and lingual gums. Damage to this nerve results in loss of sensation in its distribution but no paralysis. The lingual nerve runs beside the submandibular ganglion and duct, so there is a risk of damage or transection during dissection and ligation of the duct. Recovery depends on severity of damage but may lead to persistent numbness.

3. Facial vein: Not a nerve, but important to identify and preserve to prevent excess bleeding during dissection of the gland. The facial vein passes superficial to the submandibular gland, and receives tributaries from surrounding veins which can bleed profusely if damaged. The gland and overlying tissues should be retracted carefully to visualize and protect the facial vein during surgery.

4. Auriculotemporal nerve: Provides parasympathetic secretomotor fibers to the parotid gland via its temporal and zygomatic branches. Although not directly damaged in submandibular gland surgery, these branches lie close to the upper end of the incision and could potentially be injured, leading to minor disruption in parotid saliva secretion. Unlikely to have major clinical effects.

Other nerves like the mylohyoid, anterior belly of digastric and hypoglossal nerves lie deeper under the mylohyoid muscle and are unlikely to be damaged during routine submandibular gland excision.

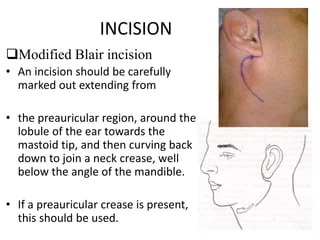

1. Patient positioning: The patient is placed in a supine position with the head turned away from the affected side. A sandbag or roll is placed behind the shoulder to extend the neck.

2. Incision: A retroauricular incision is made along the parotid notch, starting at the tragus and curving downwards and backwards around the ear lobe. The incision is deepened through skin, fascia, and SMAS layer. The greater auricular nerve is sacrificed.

3. Identify facial nerve: The main trunk of the facial nerve is identified emerging from the mastoid process. The upper and lower divisions of the nerve are traced forwards by dissecting in a superficial plane on the lateral surface of the gland.

4. Mobilize the gland: The gland is gently freed from surrounding tissues like the sternocleidomastoid muscle posteriorly and masseter muscle anteriorly using blunt finger dissection. The upper pole of the gland is detached from below the zygomatic arch. The lower pole is mobilized from the digastric muscle.

5. Ligate vessels: Facial vessels and tributaries are ligated. The external carotid artery is retracted posteriorly. The vein of parotid plexus is ligated. Any other vessels supplying or draining the gland are ligated close to it.

6. Remove the gland: The gland is removed en bloc by incising its capsule. The space is irrigated and checked for bleeding. A suction drain is inserted and closed suction drain is applied.

7. Facial nerve landmarks: The main trunk and peripheral branches of the facial nerve are identified after gland removal to check for integrity and function. The wound is temporarily closed and facial nerve stimulation performed using a probe to assess nerve function before permanent closure.

8. Closure: The incision is closed in layers – first SMAS and platysma, then subcuticular layer and finally skin using sutures. Drain usually remains for 1-2 days. Pressure bandage is applied.

Complications include facial nerve injury or palsy, salivary fistula, hematoma, wound infection, Frey’s syndrome, sialocele or keloid formation. Parotidectomy is primarily performed to remove parotid gland tumors while preserving facial nerve function.

The tongue receives sensory innervation from four cranial nerves:

1. Lingual nerve (branch of mandibular nerve CN V3):

– Provides general sensory innervation to anterior 2/3 of tongue including taste sensation (via chorda tympani branch) and touch, pain, temperature.

– Originates from mandibular division of trigeminal nerve. Descends anterior to internal carotid artery and behind posterior belly of digastric muscle.

– Emerges below mandible at posterior margin of mylohyoid muscle. Runs below mucosa on floor of mouth to reach undersurface of tongue.

2. Glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX):

– Provides sensory innervation to posterior 1/3 of tongue including taste, touch, pain and temperature sensation.

– Exits skull through jugular foramen, runs between internal jugular vein and internal carotid artery. Passes between superior and middle pharyngeal constrictor muscles to reach tongue base.

3. Facial nerve (CN VII):

– Carries taste sensation from anterior 2/3 of tongue to facial nucleus in pons via chorda tympani branch. Fibers originate in facial nerve proper and join lingual nerve.

– Damage to facial nerve before chorda tympani branch can cause loss of taste in anterior tongue. Damage proximal to nerve genu can affect both taste and saliva production.

4. Vagus nerve (CN X):

– Provides general sensation to a small area at posterior edge of tongue (lingual margin) via branch from pharyngeal plexus.

– Also carries visceral efferent fibers to tongue muscles involved in swallowing. Damage causes impaired tongue movement and gag reflex.

In summary, the lingual and glossopharyngeal nerves provide most sensory innervation of the tongue. The lingual nerve supplies the anterior 2/3 (including taste via chorda tympani). The glossopharyngeal nerve supplies the posterior 1/3.

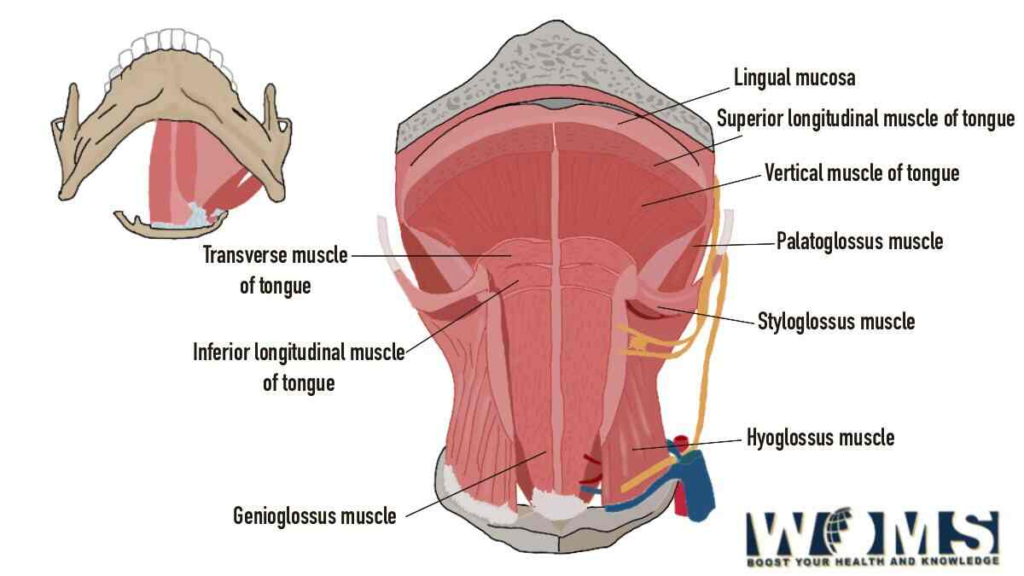

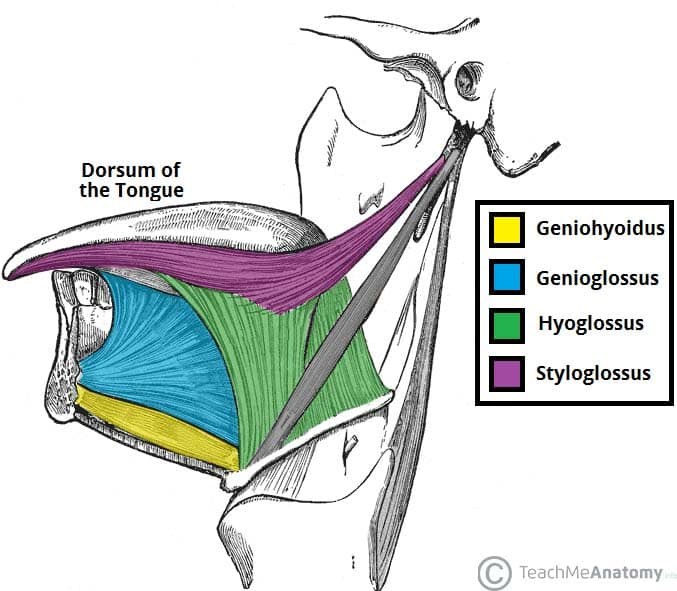

The tongue contains both intrinsic and extrinsic muscles that allow for precise movement and control. The intrinsic muscles alter tongue shape, while the extrinsic muscles act on the position and movement of the tongue.

The intrinsic muscles of the tongue include:

1. Superior longitudinal muscle: Originates at tongue root, inserts at tongue tip. Elevates and retrotrudes tongue tip.

2. Inferior longitudinal muscle: Originates at tongue root, inserts at tongue tip. Depresses and protrudes tongue tip.

3. Transverse muscle: Originates at tongue midline, inserts at edges. Narrows and thickens tongue.

4. Vertical muscle: Passes between dorsal and ventral tongue surfaces. Flattens and broadens tongue.

The extrinsic muscles of the tongue include:

1. Genioglossus: Originates at mandible, inserts at tongue body. Protrudes and depresses tongue. Major tongue protruder.

2. Hyoglossus: Originates at hyoid bone, inserts at tongue sides. Depresses tongue and draws sides downwards.

3. Styloglossus: Originates at styloid process, inserts at tongue sides. Retracts and elevates tongue sides.

4. Palatoglossus: Originates at palatine aponeurosis, inserts at tongue sides. Elevates tongue and arches tongue dorsum.

Other muscles involved in tongue movement:

– Mylohyoid: Forms floor of mouth. Supports and elevates tongue during swallowing.

– Digastric (anterior belly): Originates at mandible, inserts at hyoid bone. Raises hyoid bone and tongue during swallowing.

– Salpingopharyngeus: Originates at auditory tube, inserts at pharynx. Helps elevate pharynx and larynx during swallowing.

– Mandible: Provides bony attachment and support for many of the tongue muscles. Movement at temporomandibular joint also affects tongue position.

Damage or paralysis of tongue muscles can impair speech, chewing, swallowing and manipulation of food in the mouth.

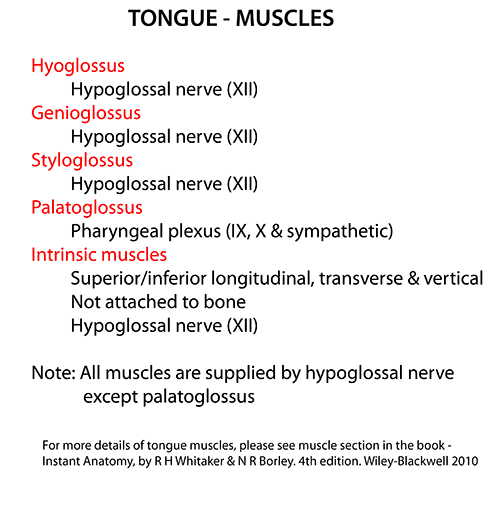

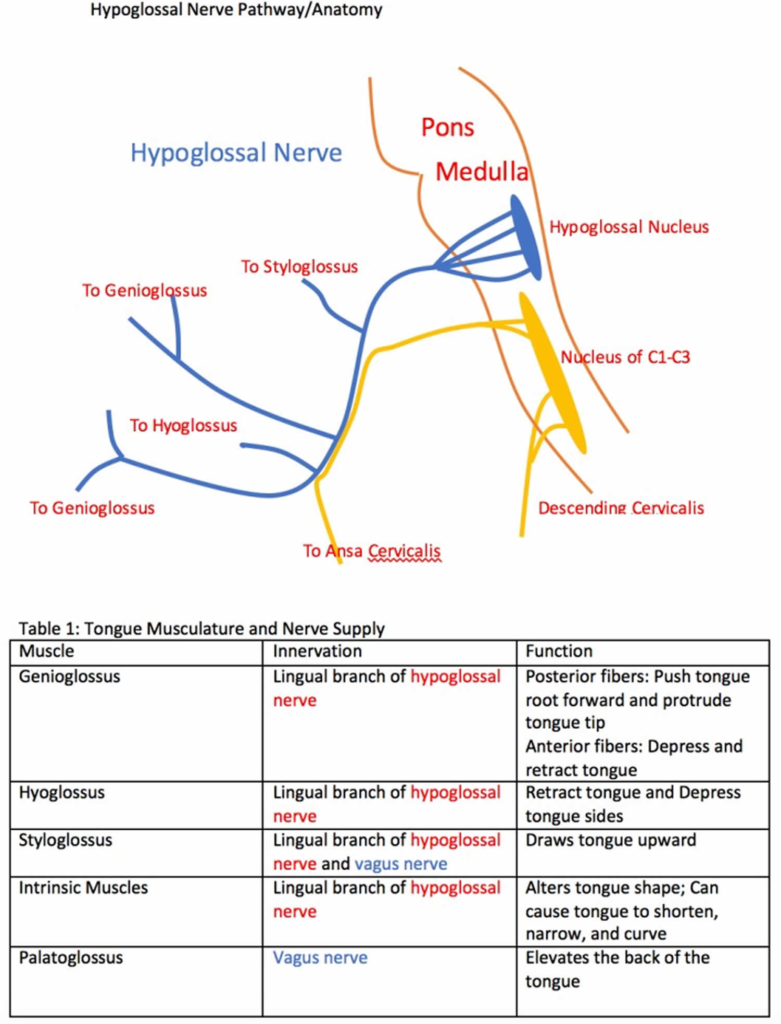

The hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) supplies motor innervation to the muscles of the tongue. It does not carry taste sensation. Key points about the hypoglossal nerve:

1. Origin: Hypoglossal nucleus in medulla oblongata. Fibers emerge from medulla to form hypoglossal nerve.

2. Exits skull: Passes through hypoglossal canal in occipital bone. Emerges between external carotid artery and jugular vein.

3. Course: Descends within carotid sheath to reach submandibular region. Curls around occipital artery and loops forwards onto hyoglossus muscle.

4. Branches: Provides motor branches to styloglossus, hyoglossus, genioglossus and intrinsic tongue muscles. Supplies all muscle groups that control tongue movements.

5. Function: Controls intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the tongue to allow protrusion, retraction, elevation, depression and lateral deviation of the tongue. Essential for speech, swallowing and chewing.

6. Clinical significance: Damage to hypoglossal nerve results in inability to move the tongue (tongue palsy) and atrophy of tongue muscles over time. There may be speech and swallowing difficulties depending on damage extent.

Taste sensation to the anterior 2/3 of the tongue is supplied by the facial nerve through the chorda tympani branch, which joins the lingual nerve. The glossopharyngeal nerve provides taste sensation to the posterior 1/3 of the tongue. This taste information is carried by special visceral afferent fibers to the rostral nucleus (taste center) of the solitary tract in the medulla. The hypoglossal nerve does not carry taste sensation, it only provides motor supply to the muscles of the tongue.

In summary, the hypoglossal nerve is responsible for motor control and movement of the tongue muscles. It does not provide taste sensation, which is carried by the facial and glossopharyngeal nerves to the medullary taste center. Damage to the hypoglossal nerve results in impaired tongue mobility leading to problems with speech, chewing and swallowing.

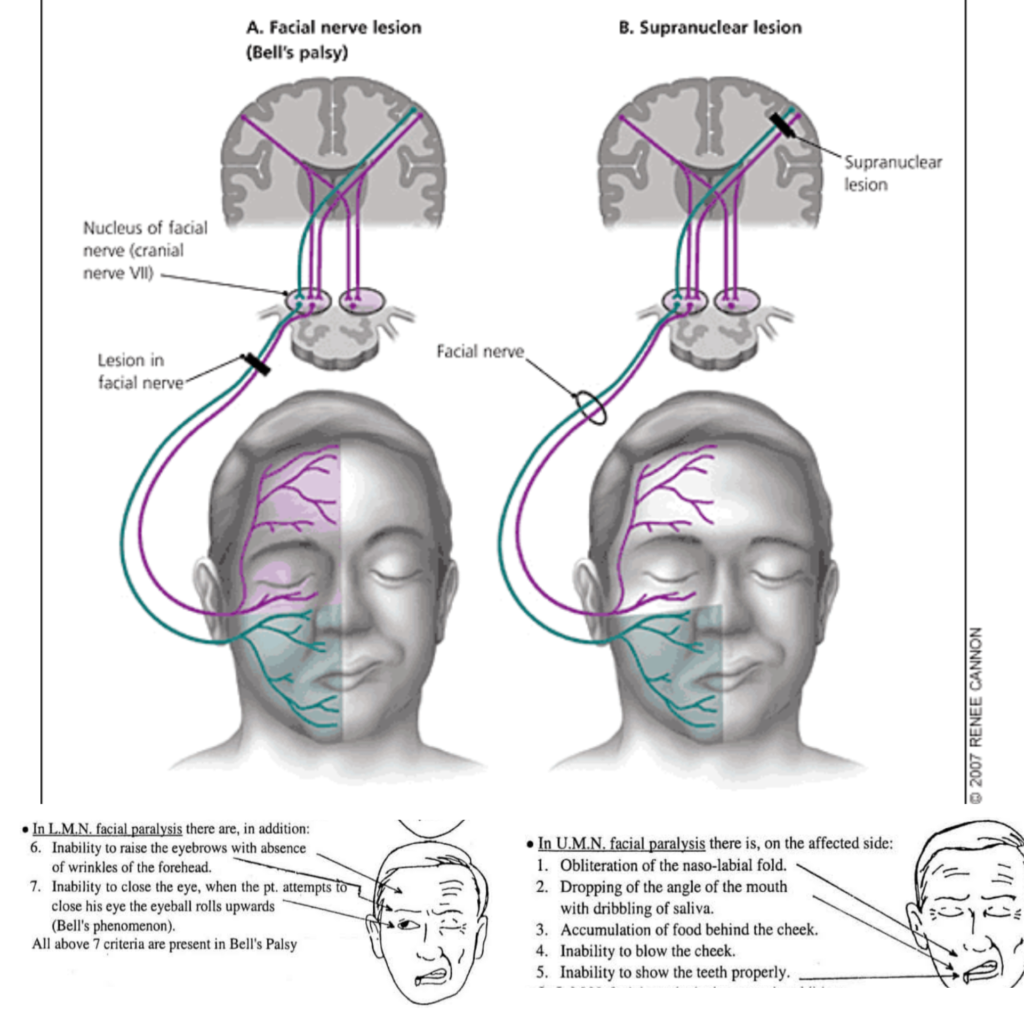

Upper motor neuron (UMN) lesions of the facial nerve originate from damage to the corticonuclear and corticobulbar tracts in the brainstem. Lower motor neuron (LMN) lesions originate from damage to the facial nerve itself. Key differences include:

UMN lesion:

• Originates above the facial nucleus in the pons – from cerebral cortex or tracts in brainstem.

• Results in contralateral facial paralysis (weakness of muscles on opposite side of face) due to loss of contralateral innervation.

• Forehead muscles are spared due to bilateral upper motor neuron innervation. Patient can still wrinkle forehead.

• No muscle wasting: Intact lower motor neurons still innervate muscles, even though they are paralyzed. Muscle tone remains.

• Hyperreflexia of jaw jerk reflex due to loss of cortical inhibition.

• Emotional expression still intact: Voluntary and spontaneous smile possible.

• Recovery depends on collateral sprouting of undamaged upper motor neuron axons which can take months. Prognosis for full recovery is poorer than LMN lesions.

LMN lesion:

• Originates from damage to the facial nerve (CN VII) – anywhere from the pons to the muscles of facial expression.

• Results in ipsilateral facial paralysis (weakness of muscles on same side of face) due to loss of innervation from damaged facial nerve.

• Entire side of face paralyzed, including forehead due to complete loss of innervation. Patient unable to wrinkle forehead.

• Muscle wasting and loss of tone due to denervation of facial muscles.

• Loss of jaw jerk reflex on affected side.

• Loss of both voluntary and emotional facial expression.

• Recovery depends on nerve regeneration and reinnervation which can take weeks to years. Prognosis depends on severity of nerve damage. Nerve grafting may be required for complete transection.

• Crocodile tears syndrome: Damage to parasympathetic fibers to lacrimal gland causes excess tearing to stimuli like eating. Due to aberrant reinnervation of gland.

The submandibular duct, also known as Wharton’s duct, drains saliva from the submandibular gland into the floor of the mouth. Key points about the submandibular duct:

1. Length: About 5 cm long. Extends from the medial side of the submandibular gland to the sublingual caruncle beside the lingual frenum.

2. Direction: Runs along the upper portion of the mylohyoid muscle, below the mucosa of the floor of the mouth. Travels upwards and medially.

3. Opening: Opens into the mouth at the sublingual papilla, lateral to the lingual frenulum, along with the minor sublingual ducts.

4. Contents: Carries primarily serous saliva from the glandular segments of the submandibular gland. Receives some mucous saliva from the sublingual gland.

5. Innervation: Receives parasympathetic fibers from the submandibular ganglion which stimulate saliva secretion. Sympathetic stimulation reduces secretion.

Surface marking of the submandibular duct:

• Locate the midpoint of the mandible. Drop a perpendicular line from here to identify the submandibular fossa.

• Divide the fossa into thirds. The submandibular duct opens into the mouth at the junction of the anterior two-thirds and posterior third.

• Place your index finger at the opening of the mouth and run it backwards below the tongue to the point where the floor of the mouth meets the lingual frenulum.

• The duct opening will be along this fold, about 1 to 1.5 cm lateral to the point where the fold joins the frenulum.

• Alternatively, have the patient roll their tongue upwards to view the sublingual undersurface. Look for small papillae in a line with the lingual frenulum. The most prominent papilla is the sublingual caruncle, marking the opening of Wharton’s duct.

• The duct can often be palpated as a firm, non-tender cord by massaging the floor of the mouth. This may express saliva or occasionally a stone if there is obstruction.

The submandibular duct transports saliva from the submandibular gland into the oral cavity. Its opening, innervation and contents are important clinical parameters. Surface marking helps locate the duct for examination, massage or surgical procedures.

The major salivary glands – parotid, submandibular and sublingual – each have a duct that opens into the oral cavity to deliver saliva. The locations of these duct openings are:

1. Parotid duct (Stensen’s duct): Opens at the buccal mucosa adjacent to the upper 2nd molar tooth. To locate, ask the patient to inflate their cheeks. The papilla marking the parotid duct opening will become prominent, lateral to the molars.

2. Submandibular duct (Wharton’s duct): Opens at the sublingual papilla beside the lingual frenulum. It can often be identified as a small papilla lateral to the frenulum, usually below the premolars.

3. Sublingual ducts (minor salivary ducts): There are 8-20 small sublingual ducts that open directly into the floor of the mouth along the sublingual fold, which lies lateral to the lingual frenulum. They open individually, anterior, and inferior to Wharton’s duct opening.

4. Other minor salivary glands: There are 600-1000 minor salivary glands located throughout the oral cavity, especially in the lips, cheeks, palate, and tongue. They each have tiny ducts that open directly into the oral mucosa. They secrete mainly mucous saliva to lubricate the mouth and help with food bolus formation.

The exact locations of the major salivary gland duct openings are:

Gland Duct Opening location

Parotid Parotid (Stensen’s) duct Opposite upper 2nd molar, buccal mucosa

Submandibular Submandibular (Wharton’s) duct Sublingual papilla beside lingual frenulum

Sublingual Sublingual (minor) ducts 8-20 ducts opening along sublingual fold, floor of mouth

The minor salivary glands have innumerable tiny ducts opening throughout the oral mucosa. Saliva from these glands helps keep the mouth moist in between meals when the major glands are less active.

The sublingual gland is a major salivary gland located in the floor of the mouth. Key points about the sublingual gland:

1. Location: Lies in the sublingual fossa, a depression on the inner aspect of the mandible below the tongue. Rests on the mylohyoid muscle and below the mucosa of the mouth floor.

2. Size and shape: Smallest of the major salivary glands. Almond-shaped, with dimensions of about 2.5 x 1.5 x 0.5 cm. Often bifurcated, giving a bilobed appearance.

3. Ducts: Has the highest number of ducts (8-20) of all the salivary glands – the sublingual ducts or minor salivary ducts. They open separately along the sublingual fold, lateral to the lingual frenulum.

4. Blood supply: Sublingual and submental arteries. Venous drainage to sublingual and facial veins.

5. Innervation: Parasympathetic secretomotor fibers from the submandibular ganglion. Sympathetic vasoconstrictor fibers.

6. Histology: Primarily mucous secreting with some serous alveoli. Mucous cells secrete gel-forming mucin that provides lubrication and aids in swallowing and speech.

7. Saliva: Secretes viscous, mucin-rich saliva that is more alkaline and less abundant than parotid saliva. Provides lubrication for the oral cavity with high mucin content.

8. Pathology:

– Blockage of sublingual ducts can lead to mucus extravasation cysts. Treatment is by unroofing cyst and marsupializing duct.

– Rarely, sublingual gland tumors occur, mostly adenomas or adenocarcinomas. May require partial or total removal of gland depending on extent.

– Sjogren’s syndrome can damage sublingual glands, leading to dry mouth. Lubricants and medications may provide relief.

– Infection of sublingual glands (sialadenitis) usually resolves with oral antibiotics and hydration. May require steroid anti-inflammatory agents for swelling.

The sublingual gland secretes mucous saliva through 8-20 sublingual ducts opening in the floor of the mouth. It helps lubricate the mouth and aids in swallowing, speech and maintenance of oral health. Disorders of the gland are not uncommon but less frequent than parotid or submandibular gland diseases.

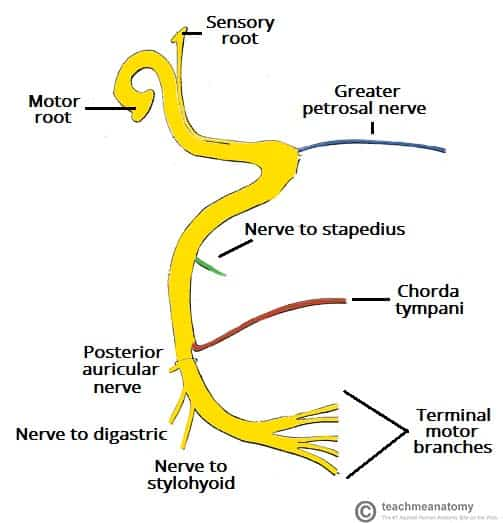

The facial nerve (CN VII) has a complex course through the facial canal, parotid gland and face. It provides motor innervation to the muscles of facial expression and parasympathetic secretomotor fibers to salivary glands.

The facial nerve originates from the facial nucleus in the pons. It enters the internal auditory meatus with CN VIII to pass through the facial canal in the temporal bone. Along its course:

– It sends a nerve branch to the stapedius muscle.

– The chorda tympani branch is given off. It carries taste sensation from the anterior 2/3 of the tongue and parasympathetic fibers to the submandibular and sublingual glands.

– The greater petrosal nerve exits to relay at the pterygopalatine ganglion. It provides secretomotor innervation to the lacrimal gland.

The facial nerve emerges from the stylomastoid foramen to enter the parotid gland, where it divides into 5 branches:

1. Temporal: Supplies frontalis, orbicularis oculi and corrugator muscles. Causes eyebrow and eyelid movements.

2. Zygomatic: Supplies orbicularis oculi and zygomaticus muscles. Causes eyelid and smile movements.

3. Buccal: Supplies buccinator and zygomaticus muscles. Allows cheek movements and dimpled smile.

4. Mandibular: Supplies muscles of lower lip, chin and jaw like depressor anguli oris and depressor labii inferioris. Provides jaw and lower face movements.

5. Cervical: Supplies platysma muscle in neck which causes grimacing.

The parasympathetic secretomotor fibers leave the facial nerve with the chorda tympani and greater petrosal nerves to stimulate saliva secretion from submandibular, sublingual and lacrimal glands respectively.

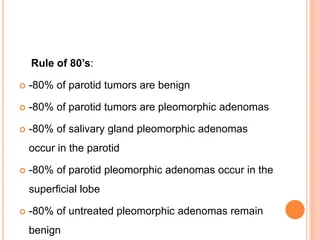

The most common benign tumors of the parotid gland are:

1. Pleomorphic adenoma:

• Most common parotid tumor, accounts for 60-70% of all parotid masses. Also called benign mixed tumor.

• Originates from ductal reserve cells. Contains epithelial and myoepithelial cells arranged in glandular, cystic and mesenchymal patterns.

• Presents as a firm, painless, slow growing mass. Usually mobile and superficial but may become fixed to facial nerve or deep lobe.

• Treatment is total superficial parotidectomy without facial nerve dissection. Recurrence rate < 5% with adequate excision. Malignant change is rare but possible.

• Usually a solitary tumor but may be bilateral in 5% of cases. Most common in 4th to 6th decades of life.

• Prognosis is excellent with complete excision. Very small risk of malignant transformation over time.

2. Warthin tumor:

• Second most common parotid tumor. Accounts for 5% of parotid neoplasms. Also called papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum.

• Originates from striated duct epithelium. Contains cystic spaces lined by papillary epithelium and lymphoid stroma.

• Presents as a slow growing parotid mass, often bilateral (30%). Soft and fluctuant. May cause discomfort or pain.

• Treatment is total superficial parotidectomy. Recurrence is extremely rare after complete removal. No risk of malignant change.

• Seen usually in elderly males, peak incidence in 7th decade of life. Prognosis is excellent after surgery.

3. Oncocytoma:

• Originates from acinic cells which accumulate mitochondria. Made up of cells with deeply eosinophilic granular cytoplasm.

• Usually presents in 6th to 8th decades as a solitary mass. Slow growing and painless.

• Treatment is total superficial parotidectomy. Recurrence rate < 5%. No malignant potential.

• Account for 1-2% of all parotid tumors. Prognosis excellent with complete surgical excision.

Other rare benign tumors include hemangioma, lymphoepithelial cyst, sialolipoma, etc. Benign parotid tumors are usually cured with superficial parotidectomy. Malignant change is rare, so total parotidectomy is not indicated except for large or fixed tumors.

The most common malignant tumors of the parotid gland are:

1. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma:

• Originates from salivary duct reserve cells. Contains mucous, epidermoid and intermediate cells.

• Most common malignant parotid tumor. Accounts for 5-10% of all salivary gland tumors.

• Usually presents as a painless, rubbery mass in the tail of the parotid gland. May cause facial nerve palsy.

• Low to high grade. High grade has increased mitosis, less cystic content and more solid areas. Higher chance of recurrence and metastasis.

• Treatment is total conservative parotidectomy with facial nerve preservation. Radiotherapy is used for high grade or inoperable tumors.

• Prognosis depends on histological grading and stage. Ranges from 90% 5-year survival for low grade to 30% for high grade disease.

2. Adenoid cystic carcinoma:

• Permeative tumor originating from intercalated ducts. Has pseudocystic spaces and forms cribriform structures.

• Painful, hard mass that infiltrates surrounding structures. Facial nerve paralysis is common due to perineural spread.

• Considered therapeutically unresectable due to extensive infiltration. Total conservative parotidectomy provides best chance for cure but often has positive margins. Requires postoperative radiotherapy.

• High chance of local recurrence and distant metastasis due to highly malignant behavior. 10-year survival around 50%. Difficult to eradicate.

3. Acinic cell carcinoma:

• Originates from acinic cells of parotid gland. Composed of solid and cystic areas containing vacuolated cells.

• Usually a solitary nodule in superficial lobe of parotid. Slow growing, nearly 80% present with a painless mass. Facial nerve paralysis is rare.

• Considered a low-grade carcinoma with good prognosis if treated. Recurrence rate of 15-20% after total conservative parotidectomy. Radiotherapy is for high grade or recurrent tumors.

• Causes up to 5% of all parotid gland malignancies. 10-year survival over 95% for low stage and grade. Prognosis poorer for high grade and recurrent tumors.

Other less common carcinomas include adenocarcinoma NOS, squamous cell carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, etc.

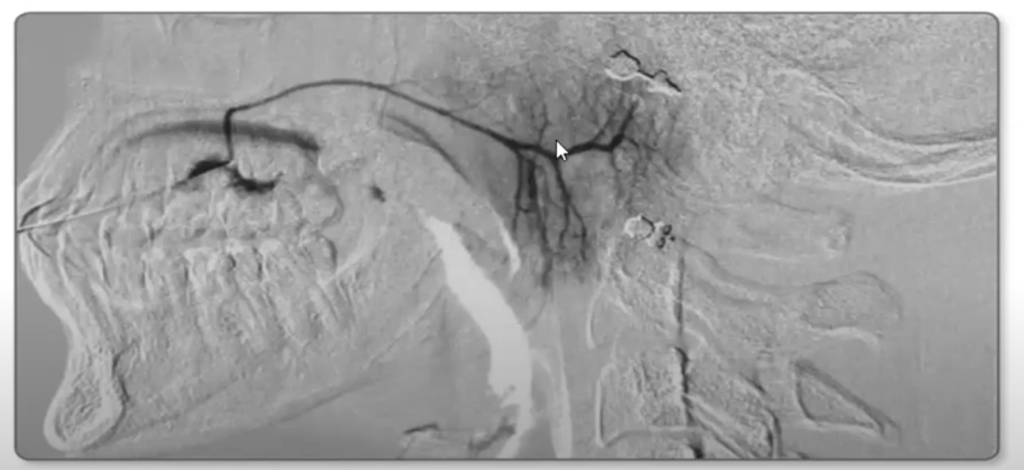

Contrast imaging studies are often used to evaluate parotid gland masses and diagnose structural abnormalities. The main modalities used are:

1. Computed tomography (CT) with contrast:

– IV contrast medium is injected to enhance visualization of parotid gland and any masses. Allows detection of tumors, inflammation, stones or anatomical variations.

– Can detect even small masses > 5mm in size. Helpful for surgical planning and biopsy guidance. Shows relation to facial nerve and lymph nodes.

– Limitations include exposure to ionizing radiation and risk of contrast medium reaction or allergy. MRI may be preferred for some patients.

2. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast:

– Gadolinium contrast medium is injected to enhance visualization of parotid glands andmasses. Provides superior soft tissue detail and higher sensitivity for tumor detection.

– MRI can detect masses as small as 1-3mm. It clearly shows tumor margins, cystic/necrotic areas, perineural spread and lymph node involvement. Multiplanar imaging allows full assessment.

– Limitations include higher cost, longer scan times, problem in patients with metallic implants/ pacemakers. Some patients experience claustrophobia during the procedure.

3. CT sialography:

– A sialogogue and contrast medium are instilled into the parotid duct to fill and outline the gland and ductal system. Detected filling defects indicate obstruction, stones, strictures or masses.

– Provides ductal images unavailable on regular CT/MRI. Useful when there are symptoms of obstruction like swelling during meals but no obvious mass on examination or other scans.

– Invasive procedure with risk of infection or damage to parotid duct. Limited utility since most diseases directly involve the gland rather than just the duct.

– Often replaced by non-invasive high resolution CT/MRI with contrast which can detect even subtle changes in the parotid gland and ductal system.

Other tests like ultrasound with Doppler, PET scan, etc may sometimes be used as adjuncts for evaluating parotid disease. But CT, MRI and sialography remain the main contrast-based imaging modalities for diagnosing parotid gland disorders.

The salivary glands can be classified in several ways:

1. By secretion:

– Serous glands: Secrete thin, watery saliva rich in enzymes. e.g. parotid glands.

– Mucous glands: Secrete thick, viscous saliva rich in mucins. e.g. sublingual glands.

– Mixed glands: Contain both serous and mucous acini. e.g. submandibular glands.

2. By size:

– Major salivary glands: Parotid, submandibular and sublingual glands. Produce 90% of unstimulated saliva.

– Minor salivary glands: 600-1000 small glands embedded in oral mucosa of lips, cheeks, palate, etc. Secretions mainly keep mouth moist between meals.

3. By anatomic location:

– Parotid gland: Largest gland, situated in front of the ear and upper neck. Stensen’s duct.

– Submandibular gland: Below lower jaw, in submandibular fossa. Wharton’s duct.

– Sublingual gland: In floor of mouth, above mylohyoid muscle. 8-20 minor sublingual ducts.

– Minor salivary glands: Widely distributed in lips, buccal mucosa, palate, tongue, etc. with small ducts opening into mouth.

4. By nerve supply:

– Parotid gland: Parasympathetic – auriculotemporal nerve, glossopharyngeal nerve.

– Submandibular and sublingual glands: Parasympathetic – submandibular ganglion via chorda tympani nerve.

– Minor salivary glands: Parasympathetic – facial nerve, glossopharyngeal nerve, vagus nerve.

5. By embryologic origin:

– Parotid gland: From ectoderm of primitive stomodeum (primitive mouth). Develops from epithelial buds in cheeks near original mouth opening.

– Other major salivary glands: From endoderm of foregut. Develop from epithelial buds in floor of pharynx which descend and become submandibular and sublingual glands.

– Minor salivary glands: Also from endoderm. Develop from epithelial buds remaining in lips, cheeks, palate, etc.

Q.surface marking of neck vessels?

The major neck vessels can be identified by surface markings and palpation. Key landmarks include:

1. Carotid artery:

– Runs vertically within the carotid sheath in the neck.

– Surface marking: Draw a line from the mastoid process to the sternal notch. The carotid pulse can be felt lateral to this line at the level of C4 vertebra.

– The right common carotid artery originates from the brachiocephalic trunk, while the left arises directly from the aortic arch. They bifurcate at C3-4 level into internal and external carotid arteries.

2. Jugular vein:

– Descends with the carotid artery within the carotid sheath. Lies posterolateral to the artery.

– Surface marking: Map the course with the same line used for carotid artery. The vein can be seen while performing Valsalva maneuver.

– Formed by union of posterior auricular and retroauricular veins. Pierces deep fascia to join subclavian vein. Valves present in lower third of vein.

3. Subclavian artery:

– Originates from the brachiocephalic trunk on right and directly from the aortic arch on left. Passes over first rib.

– Surface marking: Join lateral end of clavicle to lateral end of sternoclavicular joint. The pulse can be felt at the lateral end of the clavicle.

– Divides into axillary and internal thoracic arteries at lateral border of first rib. Supplies upper limb, lower neck and thorax.

4. Subclavian vein:

– Formed by axillary vein at lateral border of first rib. Runs with subclavian artery over first rib to join the internal jugular vein.

– Surface marking: Same as for subclavian artery. Not usually palpable clinically due to position deep under clavicle.

– Drainage of upper limb, shoulder and lower neck. Larger in caliber than subclavian artery. Has valves to facilitate unidirectional blood flow.

5. Brachiocephalic trunk:

– Originates from aortic arch, behind manubriosternal joint. Divides into right common carotid and right subclavian arteries. Left common carotid and subclavian arteries arise directly from the aortic arch.

– Surface marking: Junction of manubrium and right sternoclavicular joint. Pulse not usually palpable.

Q.xray sialography?

X-ray sialography, also known as xeromammography, is a radiographic procedure used to evaluate the salivary gland ductal system. It involves the injection of a contrast medium into the salivary ducts, followed by x-rays to outline the glands and detect any abnormalities.

Procedure:

1. The patient is placed in an upright position. A C-arm image intensifier is used to obtain real-time x-ray images.

2. The parotid or submandibular papilla is cannulated using a plastic catheter inserted into the salivary duct opening in the mouth. This may require local anesthetic spray.

3. A water-soluble iodinated contrast medium is slowly injected through the catheter using a syringe. Multiple x-ray films are taken as it fills the ductal system and gland.

4. After adequate filling and imaging, the contrast is completely aspirated to prevent excessive gland stimulation. The catheter is then removed.

5. Additional x-ray films with different projections may be taken for better visualization. Patients are observed for 30 minutes before being allowed to leave.

Interpretation:

– Normal glands will show branching ducts with homogeneous, gradual tapering. The gland outline is smooth and compact with fine septations.

– Obstruction or stone will appear as abrupt cutoff or dilation of a duct. Narrowing or stricture at any point also suggests obstruction.

– Tumor is suggested by an irregular outline, focal widening or amputation of ducts, abnormal gland shape or soft tissue mass effect. However, tumors may not necessarily distort the ducts and a normal sialogram does not exclude a mass.

– Atrophy shows complete loss or marked narrowing of major ducts due to loss of glandular tissue. Diffuse reduction in ductal caliber is seen in Sjogren’s syndrome.

– Focal swelling at gland periphery suggests extravasation due to duct rupture during cannulation or secretion. Reflux of contrast into oral cavity or other glands can also occur due to high pressures.

Sialography is often replaced by non-invasive CT/MRI sialography which provides superior soft tissue detail and diagnostic accuracy. X-ray sialography is mainly used when CT/MRI are unavailable or to confirm clinical findings indicated on these scans. The procedure is associated with radiation exposure and risks like infection, duct injury or allergic reaction.

Facial nerve involvement is more commonly seen in Sarcoidosis than Sjogren’s syndrome. Key differences include:

Sarcoidosis:

• Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease of unknown cause. It affects the lungs and lymphatic system, but can involve almost any organ.

• Cranial nerve palsies occur in about 5% of patients with sarcoidosis. The facial nerve is the most commonly affected (70%), causing peripheral facial paralysis.

• Facial nerve involvement is usually unilateral. It results from granulomatous inflammation of the nerve, especially in the area of the geniculate ganglion.

• Treatment with corticosteroids often improves or resolves the facial palsy over weeks to months. Immunosuppressants and surgery may occasionally be required.

• Other cranial nerves like optic, vestibulocochlear and hypoglossal nerves can also be affected in sarcoidosis.

Sjogren’s syndrome:

• Sjogren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands, especially salivary and lacrimal glands.

• Peripheral facial nerve palsy is rare in Sjogren’s syndrome. It is usually mild and transient, resulting from vasculitis or inflammation of glandular tissues surrounding the facial nerve.

• Facial nerve involvement tends to be bilateral in Sjogren’s syndrome. It may recur with disease flares but is not typically progressive.

• Treatment focuses on managing the underlying autoimmune condition. Corticosteroids and immunosuppressants may provide rapid improvement in facial nerve function. Surgery is rarely needed.

• Dry eyes and dry mouth due to lacrimal and salivary gland damage are much more common problems in Sjogren’s syndrome. Other organ involvement is rare.

In summary, peripheral facial nerve palsy is a well-known extrapulmonary manifestation of sarcoidosis.

The treatment of Sarcoidosis and Sjogren’s syndrome differs based on the underlying disease process:

Sarcoidosis:

• Corticosteroids: First-line treatment for moderate to severe sarcoidosis or organ threatening disease. Controls inflammation and suppresses the immune system. Oral prednisone at 0.3-0.6 mg/kg/day, tapered over weeks to months based on response.

• Hydroxychloroquine: Used for cutaneous, articular and neurological sarcoidosis. Acts as an immunomodulator with steroid-sparing effect. 200-400 mg/day in divided doses.

• Methotrexate: For recalcitrant or progressive disease. Acts by inhibiting immune cell proliferation and activity. 5-25 mg/week orally or SQ.

• Azathioprine: For refractory disease or as a steroid-sparing agent. Purine analogue that suppresses the immune system. 50-150 mg/day in divided doses.

• Antitumor necrosis factor agents: For chronic pulmonary, cardiovascular or neurological disease refractory to other treatments. Infliximab, adalimumab used at doses based on body weight infusion or SQ injection.

• Lung or lymph node resection: For isolated symptomatic lesions resistant to medical therapy or causing compressive effects. To establish diagnosis or prevent complications.

• Anticonvulsants: Required in cases with seizures until inflammation stabilizes with immunomodulation.

• Supplemental O2 and pulmonary rehabilitation: For severe pulmonary disease or respiratory failure until medical therapy takes effect.

Sjogren’s syndrome:

• Artificial tears and saliva: For dry eyes and dry mouth. Oral pilocarpine or cevimeline can stimulate remaining salivary and lacrimal gland tissue.

• Corticosteroids: For systemic disease manifestations like vasculitis, myositis, neuropathy or arthritis. Low dose prednisone with slow taper.

• Hydroxychloroquine: For joint, cutaneous and fatigue symptoms. May improve salivary flow and reduce gland inflammation.

• Immunosuppressants: In refractory cases requiring steroid sparing or stronger immune suppression. Methotrexate, azathioprine or mycophenolate used.

• Rituximab: Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody used for severe or progressive salivary and lacrimal gland disease not responding to conventional therapy. Depletes B cells.

• Supportive measures: Dry eye lubricants and ointments, oral dental care, vaginal lubricants, etc may be required depending on symptoms.

Treatment focuses on suppressing the abnormal immune response and managing symptoms. Response to therapy depends on disease severity, duration and organ involvement. Close monitoring for adverse effects is required with immunosuppressive drugs.

Epidemiology and Risk factors:

• Warthin’s tumor:

– Most common benign tumor of parotid gland

– Peak incidence in 60-70 years age group. Very rare in young.

– Strong association with smoking.

• Pleomorphic adenoma:

– Most common salivary gland tumor

– Usually occurs in 30-60 years age group. Can occur in any age.

– No known risk factors. Slightly higher in females.

Clinical findings:

• Warthin’s tumor: Slow growing, painless mass below and anterior to ear. May have ipsilateral cervical lymphadenopathy.

• Pleomorphic adenoma: Slow growing, painless, firm mass. Usually solitary and well circumscribed.

Pathological findings:

• Warthin’s tumor: Encapsulated mass with papillary infoldings, cysts and lymphoid stroma. Epithelial lining of two layers of cells: inner columnar and outer squamous cells.

• Pleomorphic adenoma: Encapsulated mass with epithelial and myoepithelial elements in chondromyxoid and hyaline stroma. Epithelial ducts and sheets of cells. Spindle-shaped myoepithelial cells.

Imaging features:

• Warthin’s tumor: Well-defined cystic mass with enhancing septations. Enhancement of papillary stalks.

• Pleomorphic adenoma: Well-defined lobulated mass. Enhancement of myxoid and fibrous stroma. Central non-enhancement due to necrosis is occasionally seen.

Treatment:

• Warthin’s tumor: Enucleation or extracapsular dissection. Recurrence is rare.

• Pleomorphic adenoma: Superficial or total parotidectomy. Higher recurrence rate if incompletely excised.

Recurrence:

• Warthin’s tumor: Extremely rare. <1%

• Pleomorphic adenoma: Reported in 2-44% cases. Higher with incomplete excision or rupture of capsule.

Malignant potential:

• Warthin’s tumor: Essentially no malignant potential.

• Pleomorphic adenoma: Rare malignant transformation to carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. The risk is higher with multiple recurrences.

In summary, while Warthin’s tumor and pleomorphic adenoma share some similar features like being benign parotid tumors, slowly growing and painless, they have distinct differences in their origin, histology, demographics, recurrence and malignant potential. A complete surgical excision with clear margins is the treatment of choice for both to minimize recurrence.

Q.sialolithiasis commonly affected gland?

Salivary gland stones, or sialolithiasis, most commonly affect the submandibular glands. This is because:

1. The submandibular duct is longer and more tortuous, with a narrower orifice. This makes it more prone to blockage and stone formation.

2. Submandibular saliva is more alkaline and viscous. This makes the saliva salts and mucin proteins more likely to precipitate out and form stones.

3. The submandibular gland produces most of the saliva during rest and unstimulated states. This leads to higher concentrations of calcium and phosphate, which can deposit in the ducts.

4. Submandibular saliva has a higher gland mucin content. Mucin degradation products may form a matrix for mineralization and stone development.

5. Submandibular calculi tend to remain confined to the duct due to the narrow opening, enlarging over years to decades. Parotid stones are more likely to pass out into the mouth.

6. Retromolar pad obscures the submandibular duct opening, preventing stones from being obvious on examination or palpation early on. Patients tend to present later with larger stones causing infection or obstruction.

In contrast:

• Parotid stones are less common due to shorter, wider duct and more serous saliva with less protein, mucin and mineral content. Stones that form often pass spontaneously into the mouth.

• Minor salivary gland stones are rare as the ducts are very short and narrow. Associated gland is often removed if a stone forms or the gland becomes damaged.

• Sublingual gland stones practically do not occur due to multiple small ducts and less viscous saliva. There is little space for large stones to form or obstruct.

Sialolithiasis occurs in the submandibular gland in about 66-94% of cases, the parotid gland in 5-30% of cases and very rarely in minor salivary glands. Prompt diagnosis and management is needed to relieve symptoms, prevent complications and salvage gland function. Treatment may involve stone removal, sialendoscopy, lithotripsy or excision of the affected gland.

The treatment of salivary gland stones (sialolithiasis) depends on the location and size of the stone, symptoms caused and patient preference. Options include:

1. Stone removal: Small stones located near the salivary duct opening can be lifted out using wire loops, mini forceps or balloon catheters. Local anesthetic is usually sufficient and minimal trauma is caused to the duct.

2. Sialendoscopy: For stones located higher up in the salivary duct system. A microendoscope is inserted into the duct to locate and grasp the stone using small forceps or baskets under endoscopic guidance. Minimally invasive but requires technical expertise.

3. Lithotripsy: Useful for large stones or stones resistant to endoscopic removal. Involves breaking up the stone using shock waves to allow natural passage of fragments. May require multiple treatments based on stone hardness and size. Minimally invasive when effective.

4. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy: Similar to lithotripsy using an externally applied shock wave generator. Guided by fluoroscopy or ultrasound. Non-invasive but technically difficult for salivary stones due to anatomical location. Often less effective than endoscopic lithotripsy.

5. Sialoadenectomy: Removal of all or part of the affected salivary gland when other options are not possible or effective. Often indicated for chronic infection, multiple large stones causing obstruction, or when the affected gland has been damaged. Performed as an outpatient procedure. Lead to dry mouth if whole gland removed.

6. Supportive care: For small asymptomatic stones or when invasive treatment is not currently possible or refused by patient. May include hydration, salivary stimulants, massage, antibiotics if infection occurs. Follow up monitoring to detect any changes. Definitive treatment will eventually become necessary if symptoms develop or stone enlarges.

Damage to nerves supplying the submandibular gland can have significant effects on gland function and saliva production:

1. Facial nerve injury:

• The facial nerve carries parasympathetic secretomotor fibers to the submandibular ganglion via the chorda tympani branch.

• Damage to the facial nerve results in loss of parasympathetic stimulation to the submandibular gland. This leads to decreased salivary flow from loss of neurotransmitter release (acetylcholine).

• The degree of salivary hypofunction depends on whether the nerve damage affects the chorda tympani branch only or also the greater petrosal nerve which supplies the submandibular ganglion. More extensive damage leads to greater loss of saliva production.

• There may be increased mucus and protein content in the residual saliva due to loss of serous acini stimulation. The saliva becomes thicker and more viscous.

• Sympathetic stimulation from the superior cervical ganglion remains intact. This can provide some continued salivary secretion, especially in response to mastication or environmental factors. But the volume is less than normal parasympathetic/sympathetic stimulation.

2. Hypoglossal nerve injury:

• The hypoglossal nerve is a motor nerve that supplies intrinsic and extrinsic tongue muscles affecting tongue movement, speech and swallowing. It does not directly supply or stimulate the submandibular gland itself.

• Damage to the hypoglossal nerve alone does not cause significant change in submandibular salivary function or volume. Saliva production is dependent on parasympathetic or sympathetic neural input, not tongue mobility.

• However, severe or bilateral hypoglossal nerve damage can impair tongue movements required for adequate salivary gland massage and secretion during oral activities like chewing or swallowing. This may lead to reduced salivary flow from impaired gland stimulation and compression.

• Hypoglossal nerve damage also affects tongue positioning and movements that aid in directing the flow of saliva and swallowing. Some saliva may escape from the mouth or trace escape down the cheek. But there is no direct loss of salivary gland innervation or function.

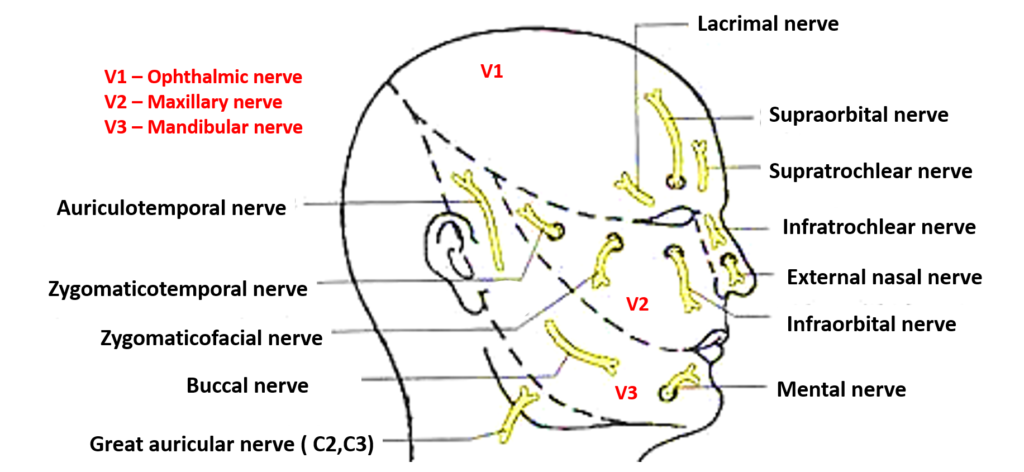

Q.nerve supply of face?

The main nerves that supply the face are:

1. Facial nerve (CN VII):

• Emerged from stylomastoid foramen and enters parotid gland. Divides into 5 branches: temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular and cervical.

• Provides motor innervation to muscles of facial expression and stapedius muscle in middle ear. Controls eye closure, smile, frown, etc.

• Conveys taste from anterior 2/3 of tongue and secretomotor fibers to submandibular, sublingual and lacrimal glands via chorda tympani branch.

• Damage causes ipsilateral facial paralysis, dysgeusia, dry eye and dry mouth depending on severity.

2. Trigeminal nerve (CN V):