RHD/ AS/IE

Q . Pathophysiology (How aortic stenosis occur ? )

Aortic stenosis occurs due to progressive thickening and calcification of the aortic valve leaflets. There are three main pathological processes that contribute to aortic valve thickening and stenosis:

1. Lipid accumulation: Lipids, cholesterol and triglycerides can accumulate on the aortic valve leaflets, especially on the aortic side of the leaflets. This is similar to the process of atherosclerosis. The accumulated lipids can induce inflammation in the valve leaflets.

2. Inflammation: The lipid accumulation triggers an inflammatory response, with macrophages ingesting the lipids. This inflammatory process leads to thickening and scarring of the valve leaflets. Over time, the leaflets become stiff and calcified.

3. Calcification: Calcium deposits form on the leaflets, further limiting their mobility. Severe calcification prevents the leaflets from opening fully, which obstructs blood flow from the left ventricle into the aorta. This causes the characteristic symptom of chest pain, syncope and heart failure seen in severe aortic stenosis.

In summary, a combination of progressive lipid accumulation, inflammation and calcification results in thickening and fusion of the valve leaflets, leading to narrowing of the aortic valve opening. Age is a major risk factor, as all these degenerative changes become more prominent over time. Other risk factors that can accelerate the disease process include hypertension, smoking, diabetes and elevated cholesterol levels.

The pathological progression from a normal trileaflet aortic valve to a severely stenosed valve typically takes many years. Gradual worsening of symptoms usually coincides with increasing severity of the valve narrowing. In some patients, rapid acceleration of disease can lead to acute heart failure and even death without surgical intervention.

Q. Major causes of aortic stenosis?

tThree major causes of aortic stenosis:

1. Congenital: Congenital aortic stenosis occurs due to abnormalities present at birth that affect normal development of the aortic valve. This includes conditions like bicuspid aortic valve (two leaflets instead of three) or unicuspid valve (single leaflet). Congenital AS tends to cause problems earlier in life.

2. Degenerative or calcific: This is the most common cause and occurs due to progressive calcification and scarring of a normal trileaflet aortic valve. It is an age-related degenerative process and usually presents in older adults (age 65+). Risk factors like hypertension, smoking and elevated cholesterol accelerate the calcification and stenosis.

3. Rheumatic: This occurs due to scarring and fusion of valve leaflets secondary to rheumatic heart disease following strep throat infection (group A streptococcus). Rheumatic aortic stenosis tends to appear earlier (age 40-60) and can progress rapidly, causing valve damage over months to years. It is more common in developing countries and has declined in incidence in Western nations.

Congenital AS often requires early surgical intervention, while degenerative AS can sometimes be managed medically before progressing to the point of needing valve replacement. Rheumatic AS also tends to need surgery, often urgently due to rapid progression.

Q. Aortic valve endocarditis, after a while weakness in Arm ?

Aortic valve endocarditis can lead to thromboembolic events like strokes due to embolization of infected or thrombotic material from the diseased aortic valve. Here is a summary of how this can occur:

1. In aortic valve endocarditis, bacterial infection causes inflammation and damage to the aortic valve leaflets. This can lead to the formation of vegetations – clumps of platelets, fibrin, microorganisms and inflammatory cells – on the valve surface.

2. These vegetations are friable and prone to breaking off, releasing infected or thrombotic emboli into the bloodstream. The emboli then travel distally and can lodge in narrow arteries supplying the brain, arms, abdomen or legs.

3. If the emboli block arteries in the brain, it leads to an infective stroke called a septic embolic stroke. This can cause neurological symptoms like weakness or numbness in the arms and legs, difficulty speaking, vision problems, etc. Septic strokes tend to have an acute onset of symptoms.

4. Emboli can also block arteries in the arms (or other areas) causing pain, coldness, numbness and even tissue damage or gangrene in severe cases. Known as infective endarteritis or mycotic aneurysms.

5. In addition to embolic events, aortic valve endocarditis can directly damage the aortic valve and heart muscle, eventually causing heart failure if left untreated.

So in summary, aortic valve endocarditis poses risks of septic embolic strokes, embolization to the arms and legs causing pain/numbness/tissue damage, as well as progressive heart failure. The triad of symptoms that suggest a septic embolic event are:

1. Fever: From the underlying infection

2. Changing heart murmur: Due to aortic valve damage

3. Focal neurological signs: Weakness/numbness from stroke or arm ischemia

Early diagnosis and treatment of infective endocarditis with IV antibiotics and sometimes valve replacement surgery are critical to avoid life-threatening complications.

Q. Coagulation system not affected by warfarin ?

The intrinsic coagulation pathway is minimally affected by warfarin. Warfarin works by inhibiting vitamin K, which is required for the production of clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X – all of which are part of the extrinsic (also known as tissue factor) pathway.

The intrinsic coagulation pathway involves factors XII, XI, IX, VIII, and V. While factor IX does require vitamin K and is synthesized in the liver like other extrinsic factors, its half-life is long (24 hours) compared to the other extrinsic factors. This means that factor IX levels will not drop significantly for 2-3 days after starting warfarin, unlike the more rapid effects on extrinsic pathway factors (especially factor VII with a half-life of only 3-6 hours).

The delayed and limited effect of warfarin on factor IX and the intrinsic pathway means that the intrinsic pathway can maintain some ability to generate thrombin via factor Xa, even when the extrinsic pathway is completely blocked. This is why induction of warfarin often only produces a modest initial drop in thrombin generation, until factor IX levels fall after 48-72 hours of therapy.

However, with continued warfarin use over weeks to months, the liver’s production of new factor IX also falls due to ongoing depleted vitamin K levels. This eventual depletion of factor IX causes intrinsic pathway function to also decrease significantly. After 4-6 weeks of consistent warfarin therapy with a therapeutic INR, intrinsic coagulation activity is reduced by over 90% from baseline.

So in summary:

1. Warfarin initially blocks the extrinsic coagulation pathway by inhibiting production of factors II, VII, IX and X which require vitamin K.

2. The intrinsic pathway remains functionally active for 2-3 days after warfarin initiation due to factor IX’s longer half-life. This maintains some coagulation.

3. Over 4-6 weeks, diminished hepatic production of new factor IX causes the intrinsic pathway to also become impaired. Continued warfarin reduces overall coagulation activity by 90%+

4. Balancing warfarin to achieve a therapeutic INR (2-3) reduces thrombotic risk while still allowing some intrinsic pathway function to control bleeding risk.

Q. Define thrombus ?

A thrombus is a solid mass formed within the circulatory system from constituents of the blood like platelets and fibrin. Thrombi are commonly referred to as blood clots.

The main characteristics of a thrombus include:

1. It forms in living blood – unlike a post-mortem clot that forms after blood has left the blood vessels. Thrombi can form in both arteries and veins.

2. It is made up of platelets, fibrin, red blood cells, white blood cells and proteins from the coagulation system. The relative amounts of these components depends on the factors that triggered clot formation.

3. It is usually attached to the vessel wall at the site of formation. Parts of a thrombus can break off to form emboli which then travel through the circulatory system.

4. It causes obstruction of blood flow through the vessel, which can damage tissues supplied by that vessel. For example, arterial clots can lead to myocardial infarction or stroke. Venous clots can cause pulmonary embolism.

5. It usually forms due to changes in one or more factors of Virchow’s triad:

1. Endothelial injury or dysfunction

2. Hypercoagulability or excess clotting factors

3. Stasis or slow blood flow

The most common causes of thrombus formation include atherosclerosis, stasis of blood flow (immobility), and inherited or acquired clotting disorders.

Anticoagulant and thrombolytic medications are often used to prevent and treat thrombi by inhibiting clot formation or dissolving existing clots. Lifestyle changes and treating underlying conditions may also help lower the risk of recurrent thrombus formation.

Q. After metallic valve , patient developed IE, why the valve should be removed?

In a patient with prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE), surgical removal and replacement of the infected valve is often necessary for the following reasons:

1. The infected valve acts as a septic focus that continues to seed bacteria into the bloodstream despite antibiotic therapy. Removal of the valve eliminates this septic source and reduces bacterial load, improving the effectiveness of antibiotics.

2. The infection around the valve can cause destruction of surrounding cardiac tissues (abscesses, fistulas) and dehiscence or detachment of the valve from the annulus. This severe valve dysfunction requires emergency surgery to avoid catastrophic complications like heart failure or cardiogenic shock.

3. Vegetations on the infected valve are prone to embolization, frequently causing septic embolic strokes, endocarditis, or other life-threatening embolic events. Valve replacement/removal helps reduce this risk of embolism.

4. Medical therapy alone often cannot sterilize an infected valve or completely clear vegetations/abscesses. Surgery provides a better chance of cure by physically removing infected and damaged tissues before repairing or replacing the valve.

5. Prosthetic valves are inherently more prone to infection due to being foreign materials in the body. Even with treatment, the risk of relapse or reinfection remains high if the valve is left in place. Replacement helps ensure infection is fully cleared.

6. Heart failure from worsening valve dysfunction may develop rapidly in prosthetic valve endocarditis, requiring emergency valve replacement to stabilize the patient’s hemodynamics before starting or completing a full course of antibiotics.

So in summary, the key reasons for surgical removal and replacement of an infected prosthetic heart valve are:

1. Eliminate the septic focus and source of emboli

2. Treat any valve dehiscence or heart failure

3. Enhance the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy

4. Reduce the risks of relapse or reinfection

5. Improve the patient’s prognosis and chance of cure

Q. Micrscopic branching hyphae on a removed metallic valve?

Finding microscopic branching hyphae on a removed prosthetic valve suggests infection with a fungal organism, such as:

1. Candida: Candida albicans is a common cause of fungal prosthetic valve endocarditis. It is a yeast-like fungus that can colonize prosthetic valves, especially in immunocompromised hosts. It forms pseudohyphae and spores.

2. Aspergillus: Aspergillus species are filamentous molds that can infect prosthetic valves. Aspergillus fumigatus is the most common. It forms acute branching hyphae with septae. Invasive aspergillosis has a high mortality if untreated.

3. Microsporum and Trichophyton: These dermatophytes typically cause superficial skin infections but in rare cases can infect prosthetic valves. They form long branching hyphae and spores. They tend to have a more indolent course.

Other rare causes include mucormycosis species like Mucor, Rhizopus and Absidia, and dematiaceous molds like Bipolaris and Exophiala.

Fungal PVE requires aggressive treatment including:

1. Surgical valve replacement: To remove the septic focus and tissue damage from fungal invasion. Antifungal drugs alone often cannot clear fungal PVE.

2. Prolonged antifungal therapy: For at least 6 weeks post-surgery to eradicate any residual infection. The specific drug depends on the fungal species.

3. Treatment of predisposing conditions: Such as immunosuppression, IV drug use, hyperglycemia/diabetes. This improves the effectiveness of treatment and reduces the risk of relapse.

4. Life-long monitoring: Periodic screening for fungal PVE relapse, especially fungal markers like (1->3)-β-D-glucan and galactomannan tests which may become positive again if reinfection develops.

Prosthetic valve fungal endocarditis has a high mortality rate of 40-60% with surgery and medical therapy. However, early surgical intervention combined with targeted long-term antifungal treatment does provide the best chance of cure while minimizing risks of major complications.

Q . Symptoms of AS ?

The classic triad of symptoms in patients with severe aortic stenosis includes:

1. Angina pectoris: Chest pain that occurs with exertion or stress and is relieved by rest. It is caused by insufficient blood flow to meet the increased oxygen demands of the heart muscle.

2. Heart failure: Shortness of breath (dyspnea), paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, and dyspnea on exertion. Heart failure occurs due to the left ventricle failing to empty completely with each beat, leading to pulmonary congestion and edema.

3. Syncope: Loss of consciousness, usually upon exertion. This occurs due to a drop in blood pressure and cardiac output as the stenotic aortic valve obstructs left ventricular outflow. The brain is deprived of oxygenated blood and vital nutrients, culminating in fainting or ‘passing out’.

Other symptoms may include:

•Chest pain radiating to the back, neck, jaw or arms: Due to angina with or without coronary artery disease.

•Palpitations: Heart beats feel rapid, strong or irregular due to left ventricular hypertrophy and secondary arrhythmias.

•Cough: May occur at night due to pulmonary edema, along with pink frothy sputum.

•Fatigue: Easy tiring and reduced exercise tolerance. The heart cannot increase its output enough to meet the body’s demands during activity.

•Lightheadedness or weakness: Related to exertional syncope or related drop in blood pressure.

The severity of symptoms depends on the degree of stenosis, presence of other heart disease like CAD, and adequacy of left ventricular compensation. Mild to moderate AS may be asymptomatic for years. However, once the aortic valve area reaches <1.0 cm2 (normal 2.6–3.5 cm2), or the mean pressure gradient exceeds 40 mmHg, symptoms typically develop and worsen without treatment.

Surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) is the definitive treatment for severe symptomatic AS. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is also used in high-risk patients. Prompt referral for valve intervention once symptoms appear can help prevent adverse complications from progressive left ventricular dysfunction and sudden cardiac death.

Q. Signs of AS ?

Important clinical signs in aortic stenosis include:

1. Slow rising pulse: Also known as pulsus parvus et tardus. The pulse pressure is narrow due to reduced stroke volume, and the pulse wave rises slowly due to the obstructed outflow.

2. Fourth heart sound (S4): Occurs due to stiffening of the left ventricle, which causes excess vibration during atrial filling. The S4 usually disappears with the onset of atrial fibrillation.

3. Paradoxical splitting of S2: The aortic valve closes before the pulmonic valve due to early obstruction of the former. This causes the aortic component (A2) of the second heart sound to be louder than and split from the pulmonic component (P2).

4. Aortic valve thrill: A vibration felt over the aortic area related to turbulent blood flow through the stenotic valve. It may disappear with worsening stenosis and left ventricular decompensation.

5. Aortic ejection click: High-pitched sound occurring shortly after S1 related to abrupt opening of the thickened, calcified aortic valve. It usually disappears as the valve becomes severely fused/immobile.

6. Ejection systolic murmur: Harsh, loud murmur radiating to the carotids. The intensity may decrease with severe valve obstruction due to reduced opening of the fused leaflets. The peak murmur intensity signifies the point of maximum flow in early ejection.

7. Narrow pulse pressure: Due to decreased stroke volume and aortic flow. A pulse pressure <40 mmHg in an elderly patient with normal systemic BP is highly suggestive of significant AS.

8. Displaced/hyperdynamic apex beat: The apex is displaced laterally as the left ventricle hypertrophies. The impulse may become more diffuse and less palpable with decompensation and heart failure.

Other findings include bibasilar crackles on lung exam from left-sided heart failure, peripheral edema, and a faint S1 due to valve calcification and dysfunction. Severe AS often shows one or more of these typical signs, which correspond to increasing severity and compromise in aortic valve mobility, stroke volume/flow, and left ventricular function.

Q. Complications of AS ?

Important complications of severe aortic stenosis include:

1. Angina pectoris: Chest pain due to inadequate coronary blood flow relative to myocardial oxygen demand. It occurs with exertion and stress.

2. Syncope: Loss of consciousness due to decreased cardiac output and cerebral perfusion. It usually happens upon exertion or activity.

3. Heart failure: Left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction lead to pulmonary congestion, edema, shortness of breath, orthopnea, PND, etc.

4. Pulmonary edema: Fluid accumulation in the lungs due to elevated left-sided filling pressures causes dyspnea, hypoxemia, and pink frothy sputum. It is a medical emergency.

5. Arrhythmias: Atrial fibrillation, heart block, ventricular tachycardia are common as the left ventricle becomes enlarged and ischemic. They may precipitate acute decompensation.

6. Sudden cardiac death: Closely related to the severity of valve obstruction and left ventricular hypertrophy/dysfunction. Risk is highest for aortic valve area <0.8 cm2 and mean gradient > 50 mmHg.

7. Infective endocarditis: The calcified aortic valve is prone to bacterial seeding and infection, which further damages the valve and causes embolic events. Prompt treatment with IV antibiotics and sometimes valve replacement is required.

8. Pulmonary hypertension: Left heart disease leads to increased pulmonary pressures, right ventricular hypertrophy, and eventually right heart failure.

9. Aortic fistula/aneurysm: Rare complications related to ruptured aortic root, severe aortic regurgitation, or infective endocarditis causing abscesses and valvular destruction. They require emergency cardiac surgery to avoid exsanguination.

The onset and severity of complications depends on the rate of progression of valve obstruction, adequacy of left ventricular compensation, and presence of other cardiac conditions like coronary artery disease. Mild to moderate AS may remain asymptomatic for years, but once the aortic valve area reaches <1.0 cm2 and/or the mean gradient exceeds 40 mmHg, complications become more frequent and worsen over time without treatment.

Surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement are the only treatments that can slow or reverse complications from severe AS by removing the valve obstruction. I hope this overview of potential complications in aortic stenosis is helpful! Please let me know if you have any other questions.

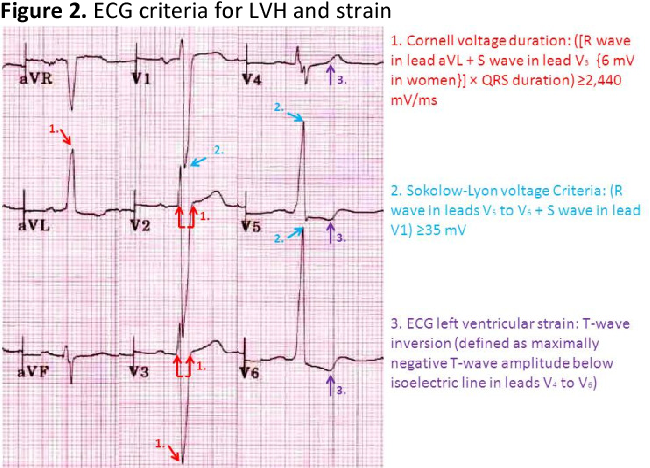

Q. ECG, what does it show?

The most common ECG finding in aortic stenosis is left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). This includes:

1. Increased R wave voltage in lateral (I, aVL, V5, V6) and precordial leads (V5, V6): As the left ventricle enlarges, the R waves become taller to reflect the increased muscle mass.

2. ST segment depression and T wave inversion in the lateral leads: Due to secondary ischemia related to increased left ventricular wall tension and oxygen demand.

3. Left atrial abnormality: The left atrium also enlarges in response to elevated LV filling pressures, causing widened broad P waves most evident in lead II >0.12 sec.

4. Left axis deviation: The mean QRS axis shifts leftward due to the increased force of left ventricular depolarization. The axis may be -30° to -90°.

5. Bundle branch block: Left or right bundle branch block can occur when severe left ventricular hypertrophy results in delayed intraventricular conduction.

Other findings may include:

•Secondary ST-T wave changes in inferior and anterior leads from left ventricular strain.

•Premature ventricular contractions: Due to left ventricular enlargement and scarring.

•Atrial fibrillation: The enlarged left atrium is prone to developing atrial fibrillation with a loss of synchronous atrial activity.

•AV block: Severe calcific AS can involve the AV node and bundle of His, progressing from 1st degree to complete heart block in some cases. Pacemaker implantation may be required.

The severity of ECG abnormalities correlates with increasing left ventricular wall thickness and hypertrophy. While the above findings are characteristic, some patients – especially the elderly – may have a normal ECG despite severe symptomatic AS. So while supportive, the ECG alone is not sufficient and echocardiography is needed to evaluate the hemodynamic severity of valve obstruction.

Management is aimed at prompt relief of valve obstruction once symptoms appear, in order to prevent ongoing end-organ damage from pressure overload and left ventricular decompensation. I hope this overview of the common ECG findings in AS is helpful!

Q. Would you still let him go for op? what would you do?

If a patient with severe aortic stenosis scheduled for aortic valve replacement surgery developed concerning symptoms or clinical changes, I would take the following steps:

1. Contact the consulting cardiologist and cardiac surgeon immediately: To discuss the change in patient condition and re-evaluate if surgery remains appropriate and urgently needed given the new developments. Surgery may need to be expedited or alternative options considered based on the severity.

2. Contact the anesthesiologist: To make them aware of the changes which could impact intraoperative management. They may want to reassess the patient to ensure their fitness for surgery and make adjustments to the anesthesia plan.

3. Perform further workup as needed: Such as repeat ECG, chest x-ray, blood work, echocardiogram. To determine if there are any new complications like pulmonary edema, ischemic changes, electrolyte abnormalities or worsening left ventricular function that require addressing before surgery.

4. Explain the situation to the patient and family: Discuss the results of the reassessment and any changes to the surgical plan. Answer any questions or concerns to keep them informed about next steps. Reassure them about close monitoring and management.

5. Decide as a multidisciplinary team if surgery should proceed today: Including input from cardiology, cardiac surgery, anesthesia and ICU staff. If surgery is not appropriate or needs delay, the operating room will need to be notified to cancel the scheduled procedure. Follow up will be required to determine when it is safe and feasible to relist the case.

6. Admit the patient for close pre-op monitoring if surgery will proceed: To enable frequent reassessments of the patient’s condition, repeat testing as needed and help optimize them medically before the valve replacement operation. The OR team will also need to remain on standby for the procedure.

7. Make appropriate consults to ICU or other services as required for perioperative management.

In summary, if concerning changes develop in a patient scheduled for aortic valve replacement, prompt reassessment including consulting the appropriate physicians and specialists is required. A multidisciplinary team approach helps determine if surgery should proceed today, needs to be expedited or delayed to enable further optimization and management of complications. Ongoing monitoring and frequent communication with the patient about the plan of care is also important.

Q.if cancel the operation, what are you worried about?

If aortic valve replacement surgery needs to be cancelled or delayed in a patient with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, there are several major concerns:

1. Worsening left ventricular dysfunction: The longer severe valve obstruction persists, the more damage occurs to the left ventricle from chronic pressure overload. This can lead to irreversible myocardial fibrosis, systolic and diastolic heart failure which does not fully recover even after valve replacement. Surgery should be performed before LV ejection fraction drops below 50% for the best outcomes.

2. Increased risk of sudden cardiac death: Patients with an aortic valve area <0.8 cm2, mean pressure gradient > 50 mmHg, and severe symptoms related to AS have a higher risk of sudden death due to malignant arrhythmias or cardiovascular collapse. Urgent surgery helps prevent this catastrophic complication.

3. Development of unstable angina or acute pulmonary edema: These life-threatening conditions signify critical aortic stenosis that requires emergency valve replacement. Medical management may not be sufficient, and surgery is the only option to relieve the obstruction and stabilize the patient.

4. Progressive valvular damage and cardiac remodeling: Long standing AS leads to severe leaflet calcification, commissural fusion and left ventricular hypertrophy. This complicates the surgical procedure and may prevent valve repair, necessitating replacement instead. It also leads to less optimal functional recovery of the left ventricle postoperatively.

5. Irreversible end-organ damage: Chronic low cardiac output from severe AS can ultimately cause permanent injury to the kidneys, liver, brain, and other systems. Seeking prompt relief of valve obstruction helps minimize multi-organ dysfunction which negatively impacts quality of life and long term prognosis.

6. Higher perioperative morbidity and mortality: Patients undergoing surgery for critical aortic stenosis with decompensated heart failure or multiple complicating conditions have significantly worse outcomes compared to those with New York Heart Association class II-III symptoms.

In summary, delaying or cancelling aortic valve replacement in severe AS when the patient has developed unstable symptoms or end-organ damage often leads to poorer outcomes and long term results. While no surgery is without risks, operating before left ventricular function deteriorates and other life-threatening complications arise provides the best chance at survival and recovery. Close monitoring for changes and frequent re-evaluation for surgical timing are important in managing these complex patients.

Q. Need antibiotics for him?

According to guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK, patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing aortic valve replacement surgery should receive prophylactic antibiotics. This includes:

1. Antibiotics administered within 60 minutes prior to surgical incision to allow adequate tissue levels: This helps prevent surgical site infection from potential bacterial seeding during the procedure.

2. Continued antibiotics for not more than 48 hours postoperatively: Unless there are signs of infection, in which case a longer course may be needed based on culture results. Short term prophylaxis around the time of surgery is sufficient in most cases.

3. Choice of antibiotics based on locally agreed protocols for cardiac surgery: Common options include cefuroxime or co-amoxiclav (amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid). Clindamycin may be used for those with a penicillin allergy.

4. Additional antibiotics if the procedure involves implants (e.g. prosthetic valve): To prevent infection of the surgically implanted foreign materials which act as potential substrates for bacterial growth and colonization. Patients should also usually receive warfarin for 3 months post-op in this case.

5. Good sterile technique, skin antisepsis and other infection prevention strategies: Timely administration of prophylactic antibiotics is an important adjunct, but other evidence-based practices to reduce risk of surgical site infections should also be followed.

The rationale for antibiotic prophylaxis in cardiac surgery includes:

1. The procedure breaches the normal barrier defenses against bacteria including skin and sterile body cavities. This provides a route of entry for potential pathogens.

2. Foreign materials (valves, wires, sutures) are inserted, which bacteria readily adhere to and colonize. Infection of prosthetic implants is difficult to clear and may require device removal.

3. Many patients have comorbid conditions like diabetes or COPD that impair immunity and wound healing, increasing infection risk.

4. The consequences of wound infection or prosthetic implant infection in cardiac surgery can be catastrophic, including sepsis, endocarditis, and device failure. Prophylaxis helps avoid these potentially life-threatening situations.

So in summary, based on recommendations from NICE and other professional guidelines, prophylactic antibiotics administered perioperatively are an important part of the infection prevention strategy for patients undergoing valve replacement surgery for severe aortic stenosis.

Q. Diagnosis ?

A history of rheumatic fever (RF) with rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is an important diagnostic clue for aortic stenosis (AS). Key points include:

1. RHD is a sequela of RF caused by an abnormal autoimmune response to group A Streptococcus infection. Repeated episodes of RF lead to progressive valvular damage, scarring and calcification – particularly of the aortic and mitral valves.

2. The aortic valve becomes thickened, fused and ultimately severely stenotic due to chronic rheumatic inflammation. This typically occurs over decades in those with RF/RHD during childhood or adolescence. Calcification develops secondary to long-standing valve disease.

3. Other stigmata of RHD may be present, such as mitral stenosis, aortic regurgitation, mitral regurgitation or cardiomegaly on chest X-ray. The heart may show signs of biatrial enlargement from longstanding valve pathology.

4. Patients may relate a history of RF manifestations in childhood or adolescence including: migratory polyarthritis, subcutaneous nodules, chorea, and erythema marginatum. They likely received secondary prophylaxis with penicillin to prevent recurrence.

5. Echocardiography shows characteristic ‘fish mouth’ appearance of the thickened, calcified aortic valve leaflets with severely restricted mobility during systole. The valve orifice is often <1 cm2 in area with a high transvalvular mean pressure gradient.

6. AS tends to develop and progressively worsen at a relatively young age (30s-50s) compared to degenerative AS. Valve replacement is typically needed for those under 60-65 years once they become highly symptomatic.

7. Younger age of onset plus the history of RF/RHD helps differentiate this etiology from senile calcific AS, which occurs due to age-related valve degeneration in the elderly (over 65-70 years).

While rheumatic heart disease has declined dramatically in developed nations, it remains prevalent in developing countries and indigenous populations. Severe symptomatic AS of rheumatic etiology often requires prompt surgical intervention to prevent adverse outcomes related to premature valve failure and cardiac dysfunction in these younger patients.

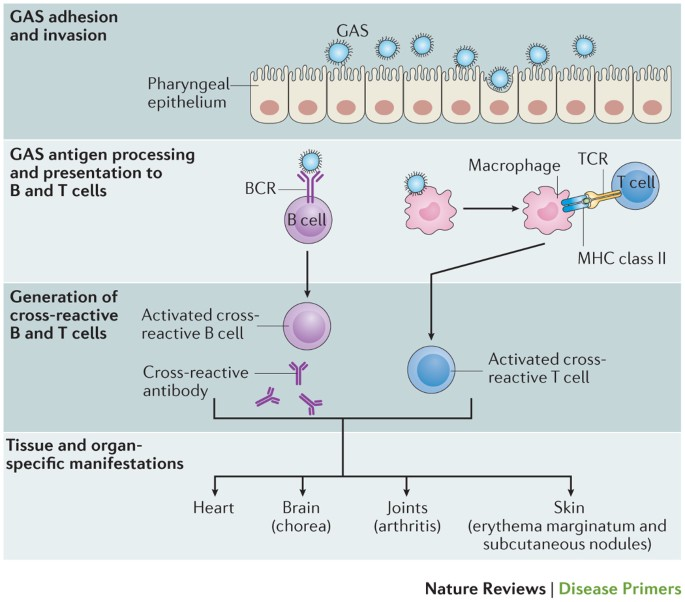

Q. Pathophysiology of RHD ?

1. RHD is a late complication of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus (GABHS) pharyngitis that manifests weeks after the initial infection. It is an abnormal autoimmune response (type II hypersensitivity) to streptococcal antigens.

2. Cross-reactive antibodies are produced that recognize both streptococcal proteins (e.g. M-proteins) as well as normal host tissue antigens (e.g. cardiac myosin, laminin). This molecular mimicry triggers an inflammatory reaction in the heart and valves.

3. There are acute (pancarditis) and chronic (valvulopathy) stages:

– Acute: Inflammation of the endocardium, myocardium, pericardium. Can cause chest pain, heart failure, arrhythmias. Resolves in weeks to months.

– Chronic: Recurrent inflammation and damage leads to valve scarring, fibrosis, retraction, leaflet thickening/fusion and eventually calcification. Causes stenosis and/or regurgitation, often of the mitral and aortic valves.

4. The mitral valve is most commonly affected (60-70% of cases) followed by the aortic valve (15-30%). The tricuspid and pulmonic valves are rarely involved. Multiple valves may be damaged simultaneously.

5. Pathologic findings include:

– Macrophage and T-cell infiltration of valve tissues.

– Fibrinoid necrosis of collagen and elastin.

– Granulation tissue formation.

– Progressive fusion and calcification of valve leaflets, especially along the commissures.

– Valve stenosis results from leaflet scarring and rigidity, while regurgitation is caused by leaflet retraction/perforation and annular dilatation.

6. Damage from RHD depends on frequency/severity of RF episodes. Early diagnosis and treatment of strep throat plus penicillin prophylaxis help limit cardiac involvement, but some degree of permanent valvulopathy often still develops.

7. Valve replacement (most commonly mitral and aortic) is frequently required at a young age due to severe stenosis/regurgitation and refractory symptoms. Tissue valves are preferred due to the need for future reoperations.

In summary, RHD provides a detailed example of how molecular mimicry and a dysregulated autoimmune response against infection can lead to chronic tissue damage and fibrosis. Ongoing inflammation and scarring of cardiac valves ultimately necessitates surgical repair or replacement to manage severe sequelae like heart failure or arrhythmias in these young patients.

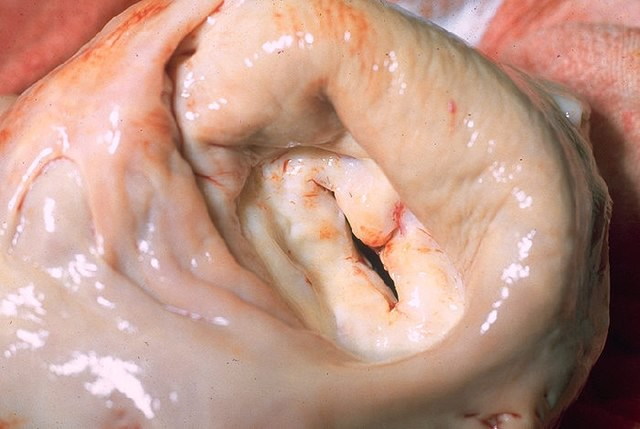

Q. Gross findings?

The gross pathological findings in rheumatic heart disease include:

Acute phase:

•Valvular vegetations (verrucae) – Irregular firm masses along lines of valve closure. Represent areas of inflammation and fibrin deposition. They cause little disturbance of valve function initially.

•Edema and congestion – Swelling and engorgement of valve tissues from inflammation. The valve becomes thickened and takes on a ‘leathery’ appearance.

•Petechiae – Pinpoint red/purple spots due to minor hemorrhages within the valve. Signifies vascular damage from acute inflammation.

Chronic phase:

•Commissural fusion – The valve commissures become adhered to each other with fibrous tissue, restricting leaflet mobility and separation. This leads to varying degrees of valve stenosis.

•Leaflet thickening and rigidity – The valve leaflets undergo fibrosis, scarring and calcification such that they no longer coapt or open properly. Can cause both stenosis and regurgitation.

•Chordae tendineae shortening and fusion – The chordae that attach valve leaflets to the underlying papillary muscles become scarred and fused. This tethers the leaflets, impairing their range of motion.

•’Fish mouth’ deformity of the mitral valve – The fused, retracted leaflets take on an appearance resembling an open fish mouth. This represents late-stage rheumatic damage with severe stenosis and little remaining leaflet mobility.

•Calcification – Widespread nodular calcium deposits throughout the valve and leaflets. Occurs in long-standing disease and produces a gritty, ‘stony’ texture. The valve becomes nearly impermeable to blood flow, causing critical stenosis.

•Annular dilation – The valve annulus enlarges due to inflammation and scarring of surrounding tissues. This leads to failure of leaflet coaptation and valve regurgitation, even if the leaflets themselves are minimally damaged or mobile.

The severity of gross pathological findings depends on the frequency, timing of treatment and control of RF episodes. In many cases, both the mitral and aortic valves show features consistent with acute and chronic rheumatic valvulitis to varying degrees. Prompt diagnosis and penicillin prophylaxis help limit ongoing tissue damage, but some degree of permanent scarring and fibrosis is often still seen.

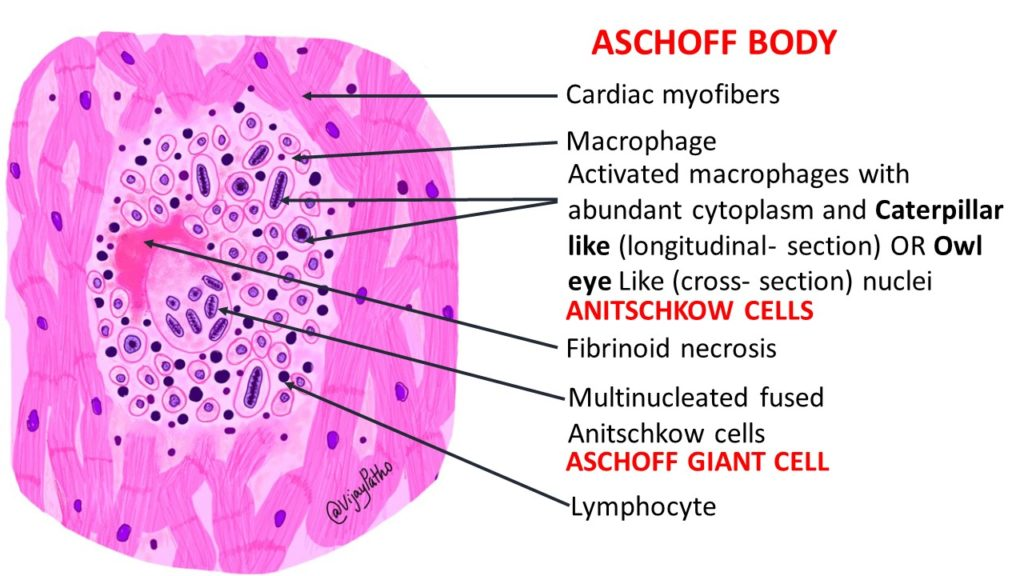

Q. Microscopic findings?

Gross findings:

1. Acute phase: Small friable vegetations (verrucae) along lines of valve closure. Usually inconsequential but may embolize. Resolve in weeks-months.

2. Chronic phase:

– Thickened, fibrosed and calcified valve leaflets with restricted mobility.

– Fusion of commissures and chordae tendineae. Leads to ‘fish mouth’ appearance of mitral valve.

– Calcific stenosis and/or regurgitation of aortic/mitral valves. Mitral valve most often affected.

Microscopic findings:

1. Aschoff bodies: Granulomatous lesions found in myocardial, endocardial and pericardial tissues. Consist of:

– Central zone of degenerating extracellular matrix (collagen/elastic fibers)

– Infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells and Anitschkow cells (activated macrophages with wavy nuclei)

– Represent foci of inflammation from RF carditis. Distinctive feature used to confirm rheumatic etiology.

2. Valvulitis: Inflammatory infiltrate, edema, fibrinoid change and scarring of valve leaflets, commissures and chordae tendineae. Leads to thickening, shortening and fusion of valve tissues over time.

3. Myocarditis: Inflammatory cell infiltrate between and within cardiomyocytes. May cause arrhythmias or heart failure during acute RF, but usually resolves without significant long term damage.

4. Pericarditis: Inflammation of the pericardial layers with fibrinous exudate. Causes chest pain, friction rub, ECG changes. Also typically transient.

5. Macrophages, CD4+ T-cells, and B-cells predominate due to cell-mediated and humoral autoimmune mechanisms in RHD.

In summary, the characteristic gross findings of valve fibrosis and distortion plus microscopic Aschoff bodies and valvulitis confirm the rheumatic etiology of heart disease during pathology examination. The severity of inflammation and scarring over multiple RF episodes determines prognosis and need for eventual valve surgery. Penicillin prophylaxis helps limit ongoing damage but may not completely halt progression once the chronic rheumatic valvulopathy has developed.

Q. Post valve replacement use of anticoagulant?

Yes, anticoagulant therapy with warfarin is typically recommended after valve replacement surgery for rheumatic heart disease. The key reasons include:

1. Prevent thrombosis on the prosthetic valve: Mechanical heart valves in particular have artificial surfaces that activate the clotting system, leading to higher risk of valve thrombosis which requires emergency surgery to prevent catastrophic obstruction. Anticoagulation helps maintain valve function and prevent this life-threatening complication.

2. Reduce thromboembolism risk: Blood clots may form on any valve prosthesis (mechanical or bioprosthetic) and embolize, causing stroke, peripheral arterial occlusion or other end-organ damage. Anticoagulation decreases the chances of clot formation and thromboembolic events.

3. Manage atrial fibrillation: Many patients develop AF due to longstanding rheumatic mitral valve disease. Anticoagulation is required to prevent clots that can form in the left atrium and atrial appendage from embolizing. Rate/rhythm control alone is insufficient.

4. Improve survival: Several studies show reduced mortality with warfarin in patients with prosthetic heart valves compared to no anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy alone. The benefits outweigh the risks of bleeding, especially for high-risk mechanical mitral valves.

The typical recommendations for anticoagulation after valve replacement include:

1. Mechanical mitral/aortic valves: Warfarin with a target INR of 2.5 to 3.5 indefinitely. Higher range for mechanical mitral valves (3.0-4.0) due to higher thromboembolism risk.

2. Tissue mitral/aortic valves: Warfarin for at least 3 months, then aspirin 75-100 mg daily thereafter. Lower risk of thrombosis but some benefit from short-term anticoagulation.

3. Additional warfarin if AF present: With a target INR of 2.0 to 3.0 to balance thromboembolism prophylaxis and bleeding risk. Duration depends on factors like successful ablation or cardioversion to sinus rhythm.

4. Bridging heparin: Used in the immediate post-op period until the INR reaches therapeutic range. Either unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) can be used based on surgeon preference.

5. Close monitoring: Requires frequent blood tests to check INR and adjust warfarin doses to maintain the target range. Diet, medications and inflammation can interact and alter INR. Patient education about drug interactions and bleeding risks is important.

In summary, anticoagulant therapy, especially with warfarin, plays an important role in the management of patients after valve replacement for rheumatic heart disease. By reducing valve thrombosis, thromboembolism and mortality, the benefits outweigh the risks of bleeding and other complications in these often young patients with prosthetic heart valves.

Q.What are the common anticoagulants ?

The common anticoagulants used in cardiology include:

1. Heparin: Binds to and activates antithrombin III which inactivates thrombin and other clotting factors (IIa, IXa, Xa, XIa). Prevents conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin.

Types:

– Unfractionated heparin (UFH): IV/SC, short half-life (1 hr), requires frequent monitoring. Used for acute anticoagulation and as bridge to warfarin.

– Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH): SC, longer half-life (3-6 hrs), more predictable dose-response so less monitoring needed. Often used for outpatient/chronic anticoagulation.

Side effects include: thrombocytopenia, osteoporosis, hypersensitivity, alopecia.

2. Warfarin: Oral vitamin K antagonist. Inhibits synthesis of clotting factors II, VII, IX and X which depend on vitamin K activation. Used for chronic anticoagulation, especially in patients with atrial fibrillation or prosthetic heart valves.

Requires frequent INR monitoring and dose adjustment. Significant diet/drug interactions and bleeding risk. Still most commonly prescribed oral anticoagulant.

3. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs): Target specific coagulation factors. Include:

– Dabigatran: Direct thrombin (factor IIa) inhibitor

– Rivaroxaban/Apixaban/Edoxaban: Direct factor Xa inhibitors

Advantages: Fixed dosing, no need for INR monitoring. Disadvantages: Cost, lack of reversibility, limited experience with prosthetic valves. Mostly used for non-valvular AF.

4. Other agents: Fondaparinux (factor Xa inhibitor), Argatroban (direct thrombin inhibitor): IV agents sometimes used as alternatives to heparin in patients with HIT/allergy or renal dysfunction.

In summary, anticoagulation for valvular heart disease and AF commonly relies on warfarin for chronic therapy due its extensive experience and low cost, as well as heparin products when rapid reversal or bridging to warfarin is needed. Newer DOACs are emerging options but lack long term data for valvular AF and are contraindicated for prosthetic valves. Close monitoring and management of the complex dosing, interactions and side effects of these agents remain important to balance the risks of clots and bleeding in often high-risk patients.

Q. Mechanisms of action of Warfarin and Rivaroxaban?

Warfarin:

– Acts by inhibiting vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR), an enzyme that recycles oxidized vitamin K to its reduced form after it has activated clotting factors II, VII, IX and X.

– By depleting reduced vitamin K, it inhibits the activation of these coagulation factors which depend on vitamin K modification for their proenzyme to active enzyme conversion.

– This delays the generation of thrombin (factor IIa) from prothrombin (factor II) and inhibits the clotting cascade, preventing thrombus formation.

– Warfarin is an indirect anticoagulant because it acts by blocking a step required for the normal activity of multiple clotting factors rather than directly inhibiting a single factor.

Rivaroxaban (and other Xa inhibitors like Apixaban/Edoxaban):

– Directly inhibit factor Xa in the common pathway of the coagulation cascade, blocking the conversion of prothrombin (factor II) to thrombin (factor IIa)

– As factor Xa catalyzes several amplification steps in the cascade, inhibiting it prevents burst activation of thrombin generation and subsequent clot formation.

Dabigatran (and other thrombin inhibitors like Argatroban):

– Directly block the action of thrombin (factor IIa), preventing it from converting fibrinogen into fibrin strands during the final common pathway of coagulation.

– Thrombin also activates factors V, VIII and XIII in the cascade, so blocking it inhibits multiple steps needed for thrombus development.

– Therefore, unlike warfarin, thrombin inhibitors act directly on a single coagulation factor rather than by depleting a factor precursor like vitamin K.

In summary, anticoagulants work at different levels in the coagulation cascade – warfarin blocks vitamin K-dependent factors (II, VII, IX, X), rivaroxaban inhibits factor Xa, while dabigatran directly blocks thrombin (factor IIa) activity. Although their mechanisms differ, they all ultimately act by preventing generation of thrombin or fibrin strands which are necessary to form and propagate blood clots.

Q. If you need it reversed urgently?

Reversal of anticoagulation may be urgently needed in some situations like life-threatening bleeding or over-anticoagulation with a supratherapeutic INR. Key steps include:

1. Assessing the bleeding risk or active bleeding: Location, severity and hemodynamic impact of any ongoing bleed which requires reversal. Also check the INR to determine the level of over-anticoagulation.

2. Determining the cause of a raised INR: Things like changes in warfarin dose, medication interactions, diet, alcohol use or liver disease can influence INR and guide reversal approach. E.g. lowering the dose or addressing an interaction may be tried first for minor INR elevation if no major bleed.

3. Choosing a reversal agent: Options include:

– Vitamin K1 (phytonadione): Replenishes depleted vitamin K stores, but reversal takes 6-12 hours as new clotting factors must be synthesized. Used for non-urgent reversal or prevention of rebound over-anticoagulation.

– Prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs): Contain factors II, IX and X as well as factor VII. Produce immediate reversal when infused but short-acting. Preferred for life-threatening bleeding when rapid INR reduction needed.

– Fresh frozen plasma (FFP): Contains all clotting factors but also other proteins which can lead to fluid overload. Slower to thaw and infuse so less useful for emergency reversal. Used when PCCs unavailable.

– Cryoprecipitate: Contains factors VIII, XIII, fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor. Used to treat hypofibrinogenemia which worsens warfarin-associated bleeding. Often given with PCC or FFP.

– Factor VIIa (NovoSeven): Highly potent source of factor VII which is rate-limiting for thrombin generation. Very fast-acting but short duration. Mainly used for intracranial hemorrhage on warfarin. Expensive, so reserved for severe, life-threatening bleeding only.

In summary, anticoagulation reversal requires rapid assessment of the clinical situation, determining the need and urgency of reversal, and administration of prothrombotic agents to increase clotting factor levels and normalize thrombin generation. For severe, active bleeding, more aggressive therapy with PCC +/- factor VII is needed to reverse warfarin’s effects within minutes. Slower agents like vitamin K may still be required to maintain long term stability. Close monitoring of INR levels, electrolytes and fluid balance is important when reversing over-anticoagulation in these critical patients.

Q. How do you monitor warfarin?

The INR (International Normalized Ratio) is used to monitor warfarin therapy. Key points about INR monitoring include:

1. INR measures the prolongation of the prothrombin time (PT) compared to a control sample from normal individuals. It is a standardized way of reporting the degree of anticoagulation with warfarin which directly inhibits production of clotting factors II, VII, IX and X – all of which are reflected in the PT.

2. The target INR depends on the clinical indication for warfarin:

– Atrial fibrillation: 2.0 to 3.0 (2.5 often used as starting range)

– Venous thromboembolism treatment: 2.0 to 3.0

– Mechanical heart valve: 2.5 to 3.5 or higher for mitral valves

– Other: Rheumatic heart disease, CAD, LV thrombus, etc. – INR 2.0 to 3.0

3. INR is monitored using a blood test to check PT (reported as INR) at least 2-3 times a week when starting warfarin or changing doses, and then every 4 to 6 weeks once stable in the target range.

4. INR results are used to adjust warfarin dosing to achieve and maintain the desired level of anticoagulation for a given patient and indication. The dose may need to be changed based on other factors like changes in diet, medications, alcohol use or illness which can influence INR.

5. An INR that is below the target range indicates under-anticoagulation and higher clotting risk, while an INR above the target range indicates excessive anticoagulation which can increase the chance of bleeding complications. The warfarin dose must be carefully adjusted in either case.

6. Patients taking warfarin require education and guidance in medication compliance, diet consistency, drug/alcohol interactions and measures like use of a medical alert bracelet or wallet card. Frequent blood tests, dose changes and the narrow therapeutic window can result in difficulties managing this treatment long term for some patients.

In summary, the INR blood test is essential for monitoring warfarin therapy to ensure patients remain within a safe and effective level of anticoagulation. Knowing the right target INR for different indications and adjusting doses carefully based on results helps minimize risks of clots and bleeding in these often complex medical cases. Patient understanding and cooperation also play an important role in enabling longer term warfarin management.

Q. Now patient fever etc you suspect ?

In a patient on warfarin with an elevated INR and signs like fever or altered mental status, infective endocarditis (IE) should be suspected. Key points include:

1. Patients taking warfarin long term for valvular heart disease or with prosthetic valves have higher risk of developing infective endocarditis, especially if sub-therapeutic INR previously.

2. Common symptoms of IE include:

– Fever: Most frequent symptom, often low-grade.

– Chills, sweating: Due to systemic inflammation/sepsis.

– Fatigue and malaise: Feelings of being unwell from the infection.

– New murmur or valvular regurgitation: Due to vegetations disrupting valve closure.

– Petechiae, splinter hemorrhages: Often on fingers/toes, due to vessel inflammation.

– Altered mental status: Can indicate embolic stroke or encephalopathy from sepsis.

3. Signs may include tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension (in severe cases) and signs of heart failure with a new or changing murmur. Stigmata of IE like Roth’s spots/splinter hemorrhages may be present.

4. 3-5 sets of blood cultures should be taken to maximize the chance of isolating the causative organism before starting empiric IV antibiotics. The modified Duke’s criteria are used to determine if clinical findings and investigations support a definite or possible diagnosis of IE.

5. Investigations like EKG, CXR, TTE/TEE (trans-esophageal echo), and eventually CT/MR may be required to check valve structure/vegetations, rule out abscesses or embolic complications. Positive blood cultures and echo findings confirm the diagnosis.

6. Treatment involves prolonged courses (4 to 6 weeks) of IV antibiotics to eradicate the infection based on cultured organism(s) and sensitivities. Surgery to repair/replace damaged valves may be urgently needed, especially with complications like rupture, heart failure, abscess or embolism.

7. Prevention of recurrence involves maintaining therapeutic INR, antibiotic prophylaxis before dental/surgical procedures, and patient education about IE risks and symptoms to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment.

In summary, fever or change in mental status in a patient on warfarin could indicate inadequate anticoagulation has allowed infective endocarditis to develop. A full workup including multiple blood cultures, echo and other imaging is needed to confirm the diagnosis. Prolonged IV antibiotics, tight control of INR and sometimes valve surgery are required to cure this life-threatening condition. Education and prevention strategies help reduce recurrence risk.

Q. Why are patients with RHD and or heart valve replacement more susceptible to IE?

Patients with rheumatic heart disease or prosthetic heart valves are more susceptible to infective endocarditis for several reasons:

1. Damaged or abnormal valve surfaces: In RHD, the valve leaflets become thickened, fused and distorted with rough, irregular areas where bloodflow is turbulent. Prosthetic valves also have artificial surfaces and joints where bacteria can attach. These abnormal areas are more prone to bacterial colonization and vegetation formation.

2. Blood stasis: Areas of damaged or prosthetic valves often have abnormal, disrupted bloodflow which stagnates, allowing bacteria to remain in one place and attach to tissues. The high pressures of heart chambers also force any attached bacteria deeper into crevices and joints.

3. Endothelial damage: The lining of damaged natural valves or artificial prosthetic valves lacks the normal intact endothelial layer found over smooth valve leaflets. This exposes deeper layers where bacteria can adhere more easily. Inflammation from the foreign material of prosthetic valves also promotes attachment.

4. Platelet aggregation: On abnormal valve surfaces and areas of endothelial damage, platelets gather and release chemicals that stimulate bacterial adhesion and colonization. Clumps of platelets form a base where vegetations develop.

5. Immune evasion: The complex structures of damaged valves in RHD and prosthetic valves provide areas shielded from normal immune surveillance and clearance mechanisms. This allows bacteria to evade host defenses and establish infection.

6. Turbulence and endothelial damage from high-pressure jets: Wherever abnormal bloodflow or high-pressure jets contact valve tissues, the friction and impact cause minor endothelial damage. This exposes new areas for bacteria to potentially colonize with each cardiac cycle.

7. Anticoagulation: The anticoagulants often required for prosthetic valves or chronic RHD may promote infection by inhibiting normal clot formation that could help wall off and limit bacterial spread in the early stages of endocarditis. A balance is needed to prevent excess clot or bleeding risk.

In summary, patients with valvular heart disease and prosthetic valves have the ‘perfect storm’ of factors predisposing to infective endocarditis including damaged or artificial valve surfaces, abnormal flow and stasis, lack of normal endothelial lining, platelet aggregation and impaired immune function. Routine antibiotic prophylaxis in high-risk groups, maintaining adequate anticoagulation, patient education and prompt diagnosis/treatment of infections are key strategies to limit risk of this serious complication.

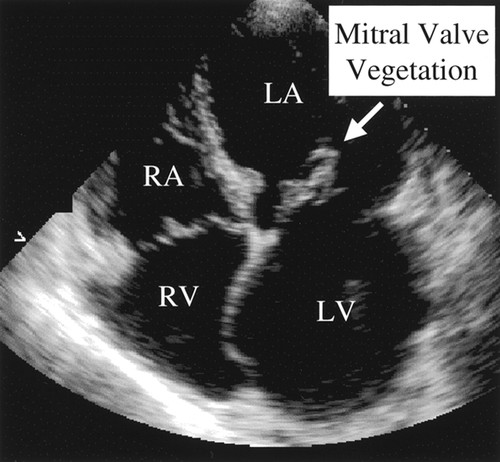

Q. What features are you looking for on 2D echo?

1. Valvular regurgitation: Seen as turbulent flow on color Doppler extending >1 cm into the receiving chamber. Regurgitant jet velocity >2.5 m/s suggests significant damage. New or increasing regurgitation is highly suggestive of IE, especially in high risk groups.

2. Valve leaflet abnormalities:

– Prolapse: Billowing of leaflets into receiving chamber.

– Coaptation failure: Leaflets fail to meet in midline, allowing backflow.

– Thickening: Leaflets >4 mm thick, often uneven.

– Reduced mobility: Leaflets have restricted opening or closing.

– Nodules: Excrescences on leaflet surfaces, often with motion independent of the leaflet. Represent vegetations.

3. Annular dilatation: The valve annulus is stretched or enlarged, impairing leaflet coaptation.

4. Chordal elongation or rupture: Chordae tendineae which control leaflet motion become lengthened, fused or rupture altogether, preventing leaflet closure.

5. Increased echogenicity of subvalvular apparatus: Bright echodense areas below the valve represent abscesses, ruptured chordae or other damage.

6. Pericardial effusion: Fluid collecting in the pericardial sac, possibly from rupture into a subvalvular abscess. Tamponade is a risk in severe cases.

7. Ventricular dilatation and dysfunction: The receiving ventricular chamber becomes enlarged, contractility is reduced. Volume overload from significant regurgitation contributes to progressive remodeling and heart failure.

Additional signs include septal perforation, fistulae, and pulmonary hypertension which can all occur secondary to severe, longstanding valve infection and destruction. Vegetations may sometimes be directly visualized as mobile masses attached to valve leaflets.

TTE -Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) provides a rapid, non-invasive assessment of patients at risk of IE. Detection of 2 or more morphological abnormalities (leaflet, annular, subvalvular) suggests probable IE based on modified Duke’s criteria. TEE may offer higher resolution views, allowing earlier diagnosis and guiding appropriate antibiotic therapy. Follow-up echos also monitor response to treatment and any changes needing surgical intervention.

In summary, comprehensive 2D and Doppler echocardiography are essential first-line tools for diagnosing infective endocarditis. Subtle indicators of disease like new regurgitation or leaflet prolapse in high-risk patients guide early suspicion, while more significant structural damage confirms active infection, prompts aggressive treatment and helps determine prognosis.