Popliteal Fossa – Anatomy Station

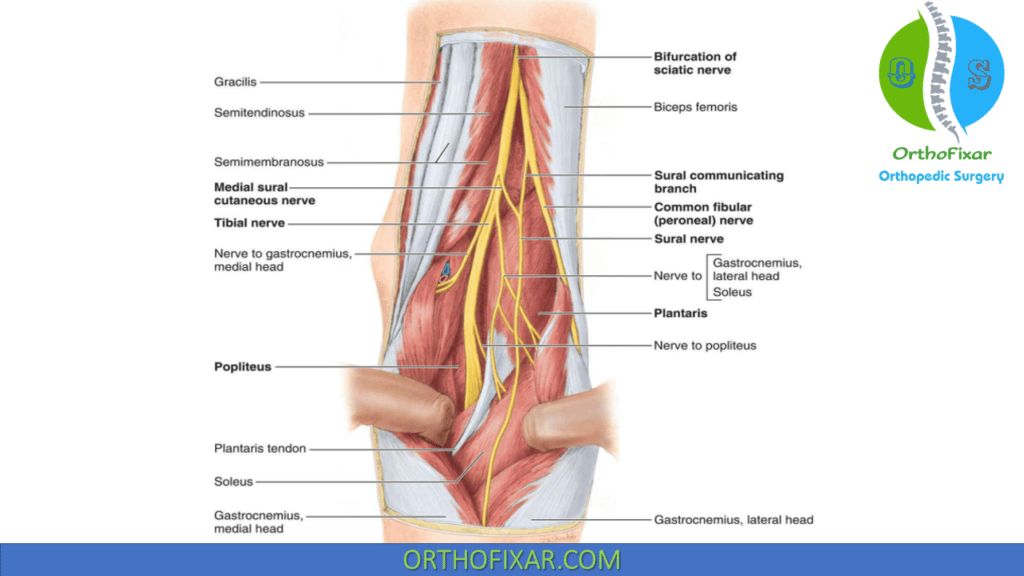

Q. Identify the structures marked?

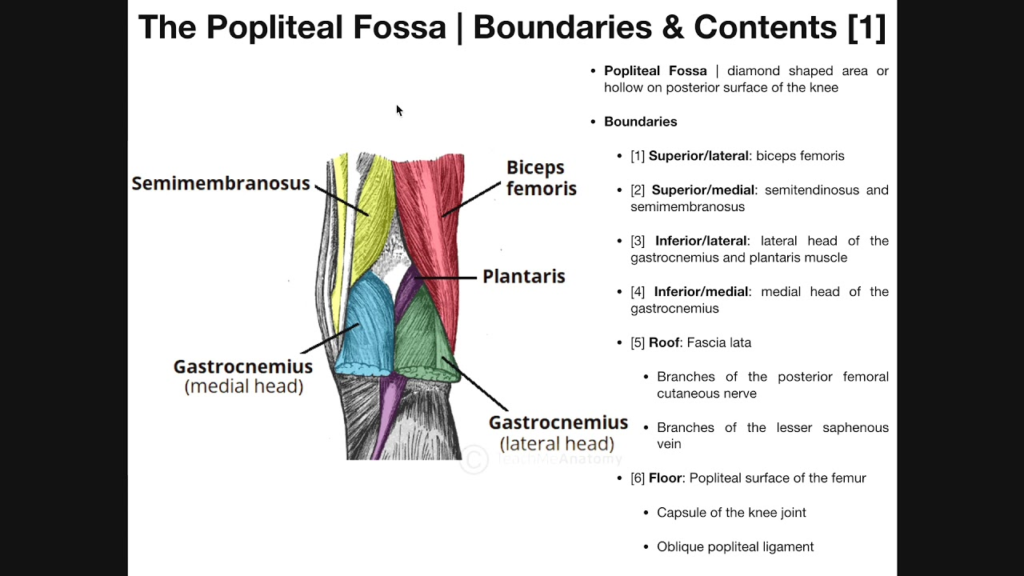

Q. overview of the popliteal fossa?

The popliteal fossa is a diamond shaped space behind the knee joint. It is bound superiorely by the hamstring muscles (semimembranosus, semitendinosus, biceps femoris), medially by the seminmembranosus and laterally by the biceps femoris. The floor is formed by the posterior surface of the femur, the posterior capsule of the knee joint and the popliteus muscle. The roof is formed by skin, superficial fascia and the popliteal fascia which is a deep fascia that stretches across the fossa.

The popliteal fossa contains important neurovascular structures:

1. Popliteal artery – the continuation of femoral artery, begins at adductor hiatus. It descends through the fossa and ends at lower border of popliteus by dividing into anterior and posterior tibial arteries.

2. Popliteal vein – forms from anterior/posterior tibial veins and small saphenous vein. Ascends through fossa to end at adductor hiatus where it becomes the femoral vein. It is the deepest structure in the fossa, lying close to artery.

3. Tibial nerve – descends in the fossa, supplies calf muscles. Divides into medial/lateral plantar nerves at lower border of popliteus.

4. Common peroneal nerve – winds around neck of fibula, supplies peroneal muscles and anterolateral leg/dorsum of foot.

5. Small saphenous vein – ascends between the heads of gastrocnemius to end in popliteal vein.

6. Lymph nodes – form popliteal node group receiving drainage from leg. Located in fat pads around neurovascular bundles.

7. Fat pads – allow mobility between structures, provide padding. Fill spaces in the fossa.

The contents of the fossa, especially the nerves and vessels, must be avoided during any procedure around the knee to prevent damage. An aneurysm, thrombus or injury can compress the contents leading to acute limb ischemia, leg swelling or pain and require urgent treatment. Tumors, lymphadenopathy or injuries in the fossa may also cause neurovascular symptoms.

The proximity of major vessels and nerves also allows access for imaging or cannulation of leg vasculature via the popliteal fossa. Knowledge of precise anatomy is important for safe and effective intervention. Damage to structures in this confined space can be immediately life or limb threatening.

Q.what is the orgin, insertion, action and nerve supply of hamstrings, gracilis and sartorius?

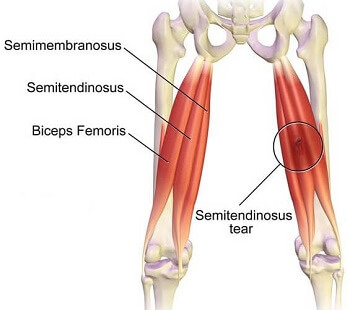

Hamstring muscles:

1. Biceps femoris:

Origin: Long head – ischial tuberosity. Short head – lateral lip of linea aspera and lateral supracondylar line of femur.

Insertion: Head of fibula and lateral tibial condyle.

Action: Flexes knee, extends hip. Laterally rotates knee.

Nerve: Sciatic nerve (tibial division)

2. Semitendinosus:

Origin: Ischial tuberosity.

Insertion: Medial side of tibial shaft below gracilis.

Action: Flexes knee, extends hip.

Nerve: Sciatic nerve (tibial division)

3. Semimembranosus:

Origin: Ischial tuberosity.

Insertion: Posterior medial tibial condyle.

Action: Flexes knee, extends hip. Medially rotates tibia.

Nerve: Sciatic nerve (tibial division)

Gracilis:

Origin: Body and inferior ramus of pubis and ramus of ischium

Insertion: Medial shaft of tibia

Action: Adducts thigh, flexes and medially rotates knee

Nerve: Obturator nerve

Sartorius:

Origin: Anterior superior iliac spine

Insertion: Medial surface of tibia

Action: Flexes, abducts and laterally rotates thigh. Flexes knee.

Nerve: Femoral nerve

The hamstrings flex the knee and extend the hip. The gracilis adducts and medially rotates the thigh as well as flexing the knee. The sartorius flexes, abducts and laterally rotates the thigh while also flexing the knee. They provide mobility and stability to the hip and knee joints.

Q. Contents of popliteal fossa anterior to posterior and medial to lateral ?

The contents of the popliteal fossa from anterior to posterior and medial to lateral are:

Anterior to Posterior:

1. Popliteal vessels – Popliteal artery and vein. The artery is the deepest structure, lying against posterior knee joint capsule. The vein is superficial to the artery.

2. Tibial nerve – Descends in the middle of the fossa under cover of vessels, divides into medial and lateral plantar nerves inferiorly.

3. Common peroneal nerve – Winds around lateral aspect of popliteal fossa, superficial to vessels. Exits fossa by passing behind biceps femoris tendon.

4. Small saphenous vein – Ascends in the fossa from between the gastrocnemius heads to join popliteal vein.

5. Fat and lymphatics – Fat pads surround the neurovascular structures. Lymph nodes lie within the fat pads.

From Medial to Lateral:

1. Semimembranosus muscle – Forms the medial boundary. Its tendon crosses the fossa.

2. Popliteal vessels

3. Tibial nerve

4. Small saphenous vein

5. Common peroneal nerve – Passes around lateral aspect of fossa.

6. Plantaris tendon (if present) – Crosses over from medial to lateral.

7. Lateral head of gastrocnemius muscle – Forms the lateral boundary.

The contents in the middle of the fossa including the popliteal vessels, tibial nerve and small saphenous vein descend in a cluster from anterior to posterior. The plantaris tendon and common peroneal nerve pass from medial to lateral, crossing behind this middle cluster. Knowing the precise arrangement of structures within the fossa is important for safe procedures in this area and understanding neurovascular pathologies that can arise.

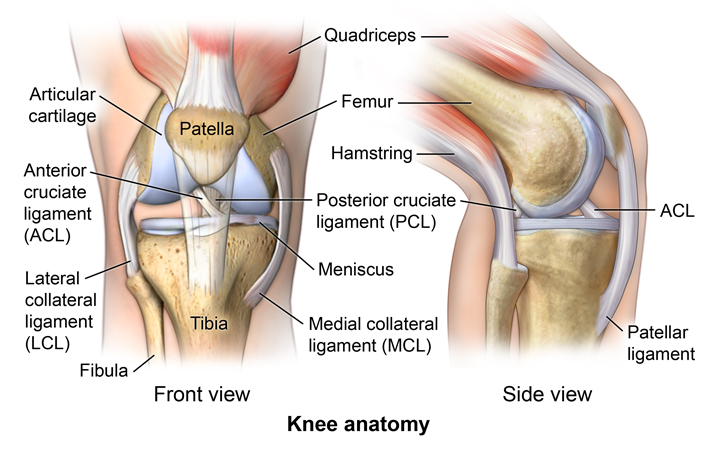

Q. Structures forming knee joint?

The knee joint is formed by the articulation of the femur, tibia and patella. The specific structures that form the knee joint are:

1. Femur: The distal end of the femur forms the superior portion of the knee joint. Its articulating surfaces are the medial and lateral femoral condyles.

2. Tibia: The proximal end of the tibia forms the inferior portion of the knee joint. Its articulating surfaces are the medial and lateral tibial condyles. The tibia also has an intercondylar eminence between the condyles.

3. Patella: The patella is the kneecap, located anteriorly within the quadriceps tendon. Its posterior surface articulates with the patellar surface of the femur.

4. Menisci: The medial and lateral menisci are c-shaped fibrocartilage pads located between the femoral and tibial condyles. They help cushion the joint and improve congruity.

5. Joint capsule: The knee joint is surrounded by an articular capsule with ligaments that provide stability. The medial and lateral collateral ligaments support the sides, while the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments cross through the middle of the joint.

6. Synovial membrane: The inner layer of the joint capsule that lines the knee joint. It secretes synovial fluid to lubricate the joint space and provide nutrition to hyaline cartilage.

7. Extensor mechanism: Formed by the quadriceps muscles and patellar tendon. It provides mobility and support for the anterior part of the knee.

8. Other ligaments: Other ligaments include the arcuate ligament, popliteofibular ligament, oblique and arcuate popliteal ligaments and posterior meniscofemoral ligaments. They provide added stability and attachments.

The complex articulation of the bones, menisci, ligaments and tendons at the knee joint allows for flexion, extension, slight rotation and knee stability during locomotion while still at high risk of injury due to its mobility. Damage to the structures forming the knee joint can lead to conditions like meniscal tears, ligament injuries, patellofemoral syndrome, osteoarthritis and fractures that impair its function.

Q. Important structures stabilising knee joint and their attachments?

The important structures that stabilize the knee joint and their attachments are:

1. Medial collateral ligament (MCL): Attaches the medial femoral condyle to the medial tibial condyle. Prevents excessive abduction of the knee.

2. Lateral collateral ligament (LCL): Attaches the lateral femoral condyle to the lateral tibial condyle. Prevents excessive adduction of the knee.

3. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL): Attaches the anterior intercondylar area of tibia to the medial wall of lateral femoral condyle. Prevents anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur.

4. Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL): Attaches the posterior intercondylar area of tibia to the posterior aspect of medial femoral condyle. Prevents posterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur.

5. Patellar tendon: Connects the inferior apex of the patella to the tibial tuberosity. Transmits force of the quadriceps to the tibia during extension.

6. Quadriceps muscles: The rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius and vastus medialis. Their tendons join to form the patellar tendon, providing dynamic stability and mobility.

7. Arcuate ligament: Extends from the fibular head to the lateral tibial condyle, providing rotational control.

8. Oblique popliteal ligament: Attaches the popliteus muscle to the lateral meniscus and joint capsule, stabilizing lateral structures.

9. Fabellofibular ligament: Attaches the lateral epicondyle to the fibular head, preventing hyperextension.

10. Posterior meniscofemoral ligament: Crosses posteriorly between femoral condyle and lateral meniscus, providing added rotational stability.

These ligaments, tendons and muscles act together dynamically and passively to coordinate stability, control mobility and enable function at the knee joint. Damage to these stabilizing structures, especially the cruciate ligaments, results in joint instability, pain, difficulty moving and early onset arthritis. Surgery to repair or reconstruct them may be needed to restore stability and biomechanics.

Q. Root value and structures supplied by tibial nerve and common peroneal nerve?

The tibial nerve and common peroneal nerve supply structures of the lower leg. Here are the roots, values and structures supplied by each nerve:

Tibial nerve:

Roots: L4-S3 spinal nerves

Sensory: Provides sensation to sole of foot and posterior calf

Motor:

– Gastrocnemius – Plantarflexes ankle, flexes knee

– Soleus – Plantarflexes ankle

– Tibialis posterior – Plantarflexes and inverts ankle

– Flexor hallucis longus – Flexes great toe, plantarflexes ankle

– Flexor digitorum longus – Flexes lateral four toes, plantarflexes ankle

Structures: Supplies posterior compartments of leg – gastrocnemius, soleus, tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis longus, flexor digitorum longus. Provides calcaneal (ankle) and plantar nerves to foot.

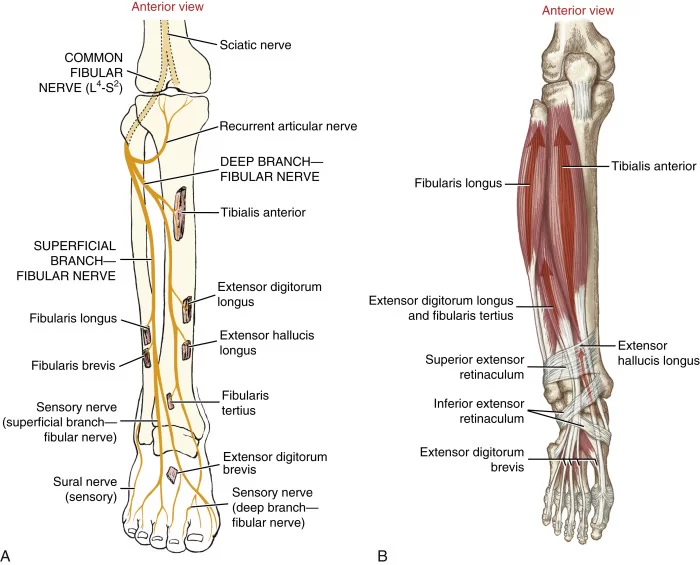

Common peroneal nerve:

Roots: L4-S2 spinal nerves

Sensory: Provides sensation to anterior and lateral lower leg and dorsum of foot

Motor:

– Tibialis anterior – Dorsiflexes and inverts ankle

– Extensor hallucis longus – Extends great toe, dorsiflexes ankle

– Extensor digitorum longus – Extends lateral four toes, dorsiflexes ankle

– Peroneus tertius – Dorsiflexes and everts ankle

– Peroneus longus – Plantarflexes and everts ankle

– Peroneus brevis – Plantarflexes and everts ankle

Structures: Supplies anterior and lateral compartments of leg – tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus, peroneus tertius, peroneus longus, peroneus brevis. Provides deep and superficial peroneal nerves to foot.

Q. what is the orgin insertion action and nerve supply of gastronemius?

The gastrocnemius muscle has the following origin, insertion, action and nerve supply:

Origin:

– Medial head: Posterior surface of medial femoral condyle.

– Lateral head: Posterior surface of lateral femoral condyle.

Insertion: Posterior surface of calcaneus via calcaneal tendon (Achilles tendon).

Action:

– Flexes knee joint: As it originates above knee, its contraction flexes knee.

– Plantarflexes ankle: Via its insertion into calcaneus, it raises heel and inverts ankle.

– Powers walking and running: The gastrocnemius, along with soleus, provides force for raising heel off ground during walking and pushes off in running/jumping.

– Stabilizes ankle: Dynamic stabilization of ankle, especially when inverted. Works with tibialis muscles.

Nerve supply: Tibial nerve – the major nerve of the posterior calf, supplies both heads of the gastrocnemius.

The gastrocnemius forms part of the superficial calf muscles, along with the soleus. Its dual innervation at the knee and ankle allows it to act on both joints. The gastrocnemius is essential for plantarflexion, raising the heel during walking, and providing push off during running and jumping. It is also important for stabilizing the ankle joint, especially when the ankle is inverted.

Damage or dysfunction of the gastrocnemius can lead to problems like:

– Drop foot: Due to weakness causing inability to raise heel and ‘slapping’ gait.

– Calf strain: From sudden overload, causing pain and tightness.

– Cramps: Painful spasms, often at night due to muscle fatigue and dehydration. Stretching and massaging the muscle relieves cramps.

– Tightness: Reduced flexibility leading to pain and secondary injuries like plantar fasciitis. Stretching prevents tightness.

– Rupture: Rare but serious tearing of the Achilles tendon attached to gastrocnemius. Causes pain, swelling and loss of plantarflexion.

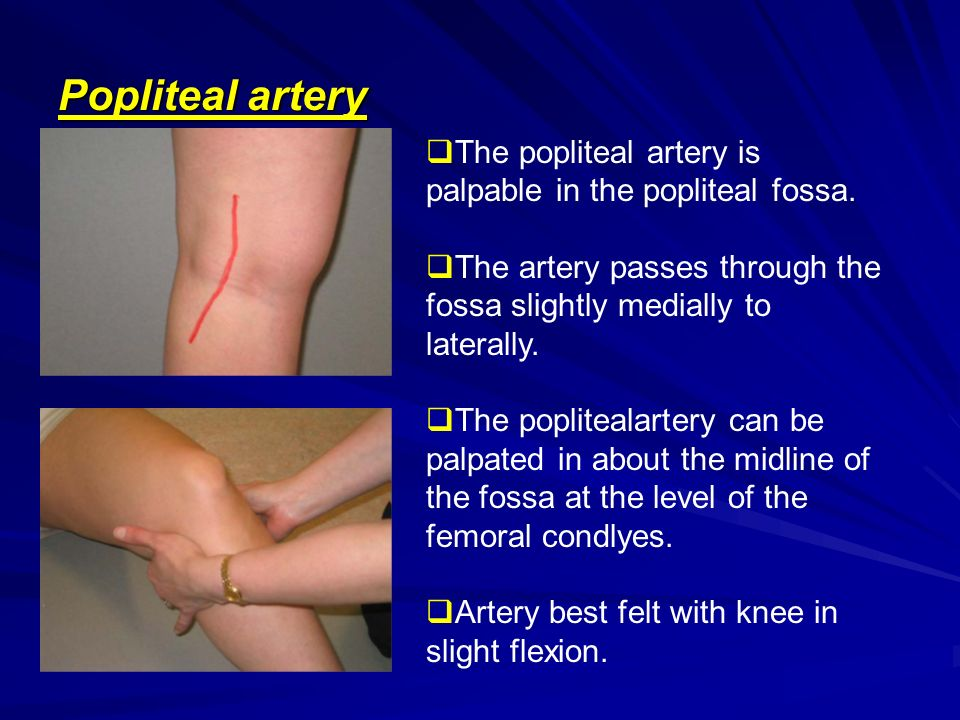

Q. How you palpate popliteal artery pulsations?

The popliteal artery pulse can be palpated through the following steps:

1. Position the patient in supine with knee slightly flexed and relaxed. This relaxes the popliteal fossa and makes the pulse more prominent.

2. Stand on the side of the patient you wish to examine. Use your index and middle finger pads, not tips, to palpate the pulse.

3. Locate the midpoint of the popliteal fossa. This is the deepest part of the hollow behind the knee.

4. Place your fingers over the midpoint, directing them inferomedially. The pulse should be felt deep to the gastrocnemius muscle.

5. Gently massage the area in small circles to help relax and soften the tissues. Apply firm and deep pressure to compress the artery against the bone.

6. Feel for a rhythmic expansion under your fingers and assess:

– Rate: Normally 60-90 beats per minute. Tachycardia or bradycardia may indicate a cardiac condition.

– Strength: A bounding pulse may indicate high blood volume, while a weak pulse could indicate peripheral arterial disease or low blood pressure.

– Regularity: An irregular, intermittent pulse can indicate cardiac arrhythmia and needs medical assessment.

7. Compare with the contralateral popliteal pulse. There should be symmetry in rate, strength and rhythm. A disparity can indicate peripheral vascular disease on the side with decreased pulsations.

8. Note any abnormalities and arrange for further investigation or management. Diminished, absent or unequal popliteal pulses can reflect systemic conditions needing treatment.

Some tips for palpating the popliteal pulse:

• Apply firm and deep pressure. Superficial palpation may miss the pulse.

• Use your fingers, not thumbs. Fingers provide greater tactile sensation.

• Relax the knee and soften tissues. Flexing and massaging the area helps bring the artery closer to the palpating fingers.

• Direct your pressure inferomedially. The pulse is located in the mid-lower portion of the popliteal fossa.

Q. Course of common peroneal nerve ?

The common peroneal nerve courses around the lateral side of the knee and descends into the anterior and lateral compartments of the leg. Its course can be described as follows:

1. Origin: The common peroneal nerve arises from the sciatic nerve in the posterior thigh, along with the tibial nerve. It contains fibers from L4 to S2 spinal roots.

2. Descends obliquely along tendon of biceps femoris muscle: The nerve passes under the biceps femoris and winds around the lateral side of the knee behind the tendon.

3. Passes through peroneal tunnel: Formed behind the fibular head by fibrous and ligamentous tissues. The nerve can be compressed here, causing peroneal tunnel syndrome with pain/numbness in its distribution.

4. Divides into superficial and deep peroneal nerves: Just below the knee, the common peroneal nerve splits into its two terminal branches.

– The superficial peroneal nerve provides sensory innervation to the lateral leg and dorsum of the foot.

– The deep peroneal nerve supplies motor function to the anterior and lateral leg compartments, dorsiflexing and everting the foot.

5. Anterior compartment: The deep peroneal nerve enters the anterior compartment between the tibia and fibula. It supplies tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus and peroneus tertius muscles.

6. Lateral compartment: The superficial peroneal nerve continues into the lateral compartment, supplying peroneus longus and brevis muscles which evert and plantarflex the foot.

7. Foot branches: Terminal branches of both superficial and deep peroneal nerves provide sensory and motor innervation to joints/muscles of the foot and toes.

The common peroneal nerve provides essential motor and sensory innervation to the lower limb, allowing dorsiflexion, eversion and sensation over the lateral/anterior leg and dorsum of the foot. Damage can result in foot drop, loss of sensation and impaired mobility.

Q. Signs and symptoms of acl injury?

The signs and symptoms of an ACL injury include:

1. Hearing or feeling a ‘pop’ at the time of injury: The ACL can rupture with sudden twisting or hyperflexion of the knee. A popping sound or sensation is common.

2. Pain: There is usually immediate pain in the knee, especially with weight bearing or movement. Swelling also develops quickly due to bleeding in the joint.

3. Knee instability: The knee may feel loose or unstable, like it is shifting or giving way. Pivoting motions can cause the knee to buckle.

4. Loss of range of motion: Pain and swelling inhibits flexion and extension of the knee. Maximal flexion is usually less than 90 degrees.

5. Positive Lachman’s test: Performed by flexing knee to 30 degrees and pulling on femur with tibia stabilized. Excessive anterior translation indicates ACL tear.

6. Positive anterior drawer test: With knee flexed to 90 degrees, the tibia moves excessively forward when pulled. Also indicates ACL rupture.

7. Effusion: Fluid builds up rapidly in the joint space, causing swelling. Aspiration may remove 30-50ml of blood tinged fluid in ACL injuries.

8. Tenderness: Pain with palpation over the anterior aspect of the knee, especially over the insertion of the ACL on the tibia.

9. Disuse atrophy: As the knee is immobilized, thigh muscles (especially quadriceps) undergo atrophy (wasting) over 4-6 weeks. Prevention uses electrostimulation.

10. Meniscal or other injuries: Concurrent meniscal tears or collateral ligament injuries are common with ACL ruptures, especially in high impact environments. Assessment should investigate other structures.

11. Giving way: Once pain and swelling have improved, the knee may still ‘give out’ during activity due to the inherent instability from the torn ACL. Bracing, physio and surgery provide support.

In the absence of major multi-ligament injuries, nonsurgical treatment (physio focused on range of motion and muscle strengthening) can be tried initially. However, ACL reconstruction is often needed for functional stability, especially in athletes, manual laborers or those with an active lifestyle. Reconstruction uses tissue grafts to replace the torn ACL.

Q. Nodes draining to popliteal fossa?

The popliteal nodes that drain the region of the knee joint and popliteal fossa include:

• Popliteal nodes: Form a chain within the popliteal fossa, draining structures around the knee. Efferent lymphatics from these nodes travel to the deep inguinal nodes.

• Posterior tibial nodes: Drain the posterior calf muscles and accompanies the posterior tibial vessels. Lymphatics drain to the popliteal nodes.

• Anterior tibial nodes: Follow the course of the anterior tibial vessels, draining the anterior leg. They also drain to the popliteal nodes.

• Superficial inguinal nodes: Receive lymphatics that arise from superficial regions of the lower limb like the foot, leg and knee. Popliteal node efferents may also drain here.

• Deep inguinal nodes: Receive efferent lymphatics from the popliteal nodes and act as a conduit for drainage into the pelvic and para-aortic nodes.

Pathology like infections, inflammation or tumors around the knee joint or in the popliteal fossa can cause swelling of these draining lymph nodes due to increased lymphatic flow. ACL injuries in particular may demonstrate popliteal node swelling due to bleeding and joint effusion.

Q. DDs of swelling in popliteal fossa?

Causes of swelling in the popliteal fossa include:

1. Baker’s cyst: A synovial fluid-filled swelling arising from the knee joint capsule. Often due to underlying arthritis or meniscal injury in the knee. Fluctuant and transilluminates. Can rupture causing calf swelling.

2. Lymphadenopathy: Enlarged popliteal lymph nodes, usually due to infection e.g. cellulitis or pathology like malignancy. Nodes will feel firm, discrete and possibly fixed. Investigation to find cause is needed.

3. Hematoma: Collection of blood in the popliteal fossa tissues from trauma like a direct blow or rupture of blood vessels. Fluctuant swelling that reduces in size over weeks with resorption.

4. Aneurysm: Swelling from a weakened and dilated segment of the popliteal artery. Pulsatile mass in the fossa, risk of thrombosis or rupture if left untreated. Requires surgical repair.

5. Ganglion cyst: Benign swelling protruding from the tendon sheaths or joint capsule. Usually painless but can cause irritation. Removed only if troublesome.

Q. How will you confirm diagnosis?

Several investigations can be done to confirm the diagnosis of popliteal fossa swelling:

1. History and physical exam: Take a detailed history of the swelling onset, progression, associated symptoms and any trauma. Examine the knee and popliteal fossa looking for signs that point to a particular diagnosis e.g. pulsatility suggests an aneurysm, ballotability indicates a cyst. Note limb posture, muscle wasting or loss of knee range of motion.

2. Ultrasound scan: First line imaging modality, useful for identifying cysts, deep vein thrombosis, lymph nodes, joint effusions, tendon tears or arterial aneurysms. Can also be used to guide aspiration or biopsy of fluid collections.

3. Doppler ultrasound: Assesses blood flow through the popliteal artery and vein. Can confirm diagnosis of aneurysm, DVT or vein occlusion. Also used when PAD is suspected as cause of calf swelling.

4. MRI scan: Provides detailed assessment of soft tissues and joints. Useful for diagnosing meniscal/ligament injuries, tendon ruptures or nerve compressions related to knee joint. Also accurately identifies cysts, ganglia, tumors and muscle pathology.

5. CT scan: May be used if MRI is contraindicated or in emergency setting. Can identify fractures, dislocations, aneurysms and large fluid collections, though less detailed for soft tissue assessment. Often done with angiography for vascular pathologies.

6. Nerve conduction studies: Assesses the common peroneal and tibial nerves for signs of compression neuropathy in popliteal fossa. Useful when symptoms like pain, weakness or sensory changes are present with non-diagnostic imaging.

7. Aspiration: Removing and analyzing fluid from a popliteal cyst, joint effusion or bursa can determine cause and rule out infection or gout. Cyst fluid that transilluminates suggests Baker’s cyst.

8. Blood tests: In suspected DVT, d-dimer levels and clotting profile may be ordered. Raised inflammatory markers can indicate infection. ESR and plasma viscosity point to conditions like PMR or malignancy.

9. Lymph node biopsy: If popliteal lymphadenopathy persists >4 weeks with unknown cause, an excision biopsy of an enlarged node may be required to rule out pathology like lymphoma or nodal spread of tumor.