Burns and ARDS

You are asked to see one 32 years old male who has been brought to A & E in an ambulance after rescuing him from fire which caught his office. You notice second degree burn on face, trunk, left arm and both thighs with soot in the nostrils and patient being restless and complaining of difficulty of breathing. Considering this critical care scenario how would you manage him?

Q. Considering this critical care scenario how would you manage him as per atls protocol?

This patient has severe burns and signs of inhalational injury, so requires immediate resuscitation and stabilization as per ATLS protocol:

1. Maintain airway: Suction airway to clear soot, secure with endotracheal intubation if unable to maintain own airway or high risk of obstruction. Give 100% oxygen.

2. Ensure adequate ventilation: Ventilate as needed, monitor oxygen saturations. Be prepared to provide respiratory support if patient develops acute respiratory distress syndrome.

3. Insert IV lines/intraosseous access: Gain two large bore IV lines for fluid resuscitation and intravenous access. Intraosseous line can be used if IV access challenging.

4. Fluid resuscitation: Initiate aggressive fluid resuscitation with warmed crystalloids like normal saline according to the Parkland formula – 4mls x Body weight x % total body surface area burned. Monitor urine output and central venous pressure.

5. Analgesia and iv fluids: Give adequate analgesia using IV opiates. Also give tetanus prophylaxis, IV antibiotics and intravenous immunosuppressants.

6. Escharotomy: May be needed if patient showing signs of chest restriction or compartment syndrome – circumferential full-thickness burns. Involve surgeons early.

7. Treat associated injuries: Look for other trauma in addition to the burns and provide necessary stabilization and management. CT scans and x-rays as indicated.

8. Admit to ICU: Admit the patient to ICU for close monitoring, fluid therapy, inhalation injury management and pain control. Ventilatory support often required with severe inhalation injury.

9. Refer to specialist centre: Transfer to a specialist burns centre if >30-40% TBSA full thickness burns as this exceeds capabilities of regular emergency centres. Requires multidisciplinary team input.

10. Further care: Eschar excision and grafting, mobilization, physiotherapy and rehabilitation, psychosocial support, nutrition, infection control and long term scar management. Multidisciplinary approach essential for best patient outcomes.

Q. Burns leads to what complication resulting in airway obstruction?

Laryngeal edema

Severe burns, especially those involving the head, neck and chest, can lead to airway obstruction and compromise through several mechanisms:

1. Heat injury to airways: Inhalation of hot gases can directly damage the airways and lungs, causing swelling, inflammation and sloughing of airway tissues- laryngeal edema. This leads to airway narrowing and obstruction.

2. Fluid shifts: Severe burns cause fluid shifts from the intravascular space into interstitial tissues. This can lead to laryngeal edema and upper airway obstruction requiring intubation.

3. Smoke inhalation: Inhalation of smoke, soot and toxic combustion products can chemically burn the airways and lungs. The byproducts of combustion may themselves cause direct airway injury, inflammation and sloughing of tissues leading to obstruction.

4. Combustion of airway structures: Direct exposure of the mouth, nose, oropharynx and trachea to fire can cause thermal destruction and obstruction of upper airway tissues. Eschar formation leads to airway blockage.

5. Bronchospasm: Irritation of airways from smoke or chemical inhalation can trigger bronchospasm, especially in patients with reactive airway disease like asthma. Bronchospasm further compromises respiratory function.

6. Diffuse alveolar damage: Widespread damage to alveoli from heat, smoke or chemical inhalation impairs gas exchange in the lungs. This can progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome, requiring ventilatory support.

7. Respiratory muscle weakness: Loss of chest wall tissue and muscles from extensive anterior burns weakens respiratory effort. This coupled with other issues like metabolic acidosis, sepsis and nerve damage contributes to respiratory failure.

8. Anemia: Significant blood loss from burn wounds reduces oxygen carrying capacity, placing further strain on respiration. Transfusion may be required.

Q. Calculate the surface area of the burn Wallace rule of nine’s ?

The Wallace Rule of Nines is used to estimate the total body surface area (TBSA) involved in burns. It allocates a percentage to areas of the body based on surface area proportions.

To calculate the TBSA burned using this rule:

1. Divide the body into 11 areas:

Head: 9%

Chest: 9%

Abdomen: 9%

Upper/mid/low back and buttocks: 18%

Arm: 9% of each arm

Forearm: 1% of each forearm

Hand: 1% of each hand

Thigh: 9% of each thigh

Leg: 9% of each leg

Feet: 1% of each foot

Genitalia: 1%

2. Examine which of the body areas have burns. Determine whether the burns are partial thickness or full thickness.

3. For each burned area, determine the percentage allocated to that area depending on severity of burn:

– Partial thickness (2nd degree) burns involving entire area: allocate full percentage for that area

– Partial thickness burns involving part of area: allocate half the percentage for that area

– Full thickness (3rd degree) burns: allocate full percentage regardless of size

4. Add together the percentages for each burned area to get the total TBSA burned.

For example:

– Patient has 2nd degree burns to entire head, abdomen, both legs and feet:

Head: 9%

Abdomen: 9%

Right leg: 9%

Left leg: 9%

Right foot: 0.5% (partially burned)

Left foot: 0.5%

Total: 37% TBSA burned

– Patient has 3rd degree burns to right arm and left anterior chest:

Right arm: 9%

Left chest: 4.5% (half of 9%)

Total: 13.5% TBSA burned

Q.who would you involve in the management of the patient?

The management of a severe burn patient requires a multidisciplinary team approach:

• Emergency physicians: Provide initial resuscitation, airway management, analgesia and fluid therapy as per ATLS protocols. Arrange admission and transfer to a burns unit if need exceeds capabilities.

• Intensivists: Manage patient in ICU including ventilatory support for inhalation injury, fluid balance, electrolyte management, pain control, nutrition and prevention of infection.

• Burns surgeons: Provide early escharotomy or fasciotomy if needed. Perform excision and grafting of burn wounds, scarring treatments and reconstructive surgeries. Also advise on positioning, physiotherapy and rehabilitation.

• Plastic surgeons: Assist in reconstructive surgeries for severe scarring and disfigurements when burns have healed. Also provide cosmetic treatments to improve appearance and function.

• Respiratory therapists: Responsible for management of ventilators, providing respiratory therapy for bronchoscopies, nebulizers, bronchodilators, physiotherapy and weaning patient from ventilation.

• Physiotherapists: Help with burn care treatments, passive/active range of motion exercises, respiratory physiotherapy, positioning, mobilization and rehabilitation activities as soon as the patient is stable to prevent long term mobility problems.

• Occupational therapists: Support patient in burn care, activities of daily living, use of splints and special masks or gloves, and counseling patients in preparation for discharge.

• Nutritionists: Provide nutritional support for the hypermetabolic burn patient. Give high calorie/protein liquid diets or tube feeds to aid with wound healing, muscle maintenance and prevention of weight loss. Monitor and address micronutrient deficiencies.

• Nurses: Provide 24 hour care including burn wound management, IV management, patient mobilisation, application of splints, administration of medications and monitoring overall condition. Educate family members and carers.

• Social workers: Support patient and family members throughout treatment providing counseling and advice on financial planning, discharge accommodation, rehabilitation and reintegration into the workforce or community.

• Psychologists: Help address trauma from burn injuries and any body image or self esteem issues. Provide coping strategies and counseling for patient and family members.

Q. where would you take care of the patient?

A severe burn patient requires treatment in a dedicated burn unit, preferably at a specialist burns center.

This is because:

1. Specialist knowledge and experience: Severe burn injuries are complex and require specialist input for best outcomes. Staff in burns centers have extensive knowledge and experience in burn treatment.

2. Dedicated burn ICU: For patients with major burns, admission to a burn intensive care unit is needed for close monitoring, airway management, ventilation, fluid resuscitation and treatment of associated conditions like inhalational injury.

3. Facilities and equipment: Burns centers have special facilities and equipment for excisional surgeries, skin grafting, scar treatments and rehabilitation not available in regular hospitals. This includes operating theaters, hydrotherapy equipment, gym facilities, compression garments and custom splints.

4. Multidisciplinary input: Burns centers provide access to a full multidisciplinary team including burn surgeons, intensivists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dietitians, psychologists, counselors and respiratory therapists which significantly improves patient care.

5. Infection control: Due to loss of skin barrier and immunosuppression, burn patients are at high risk of life-threatening infections. Burns units have high level isolation facilities and proven infection control protocols to reduce risk.

6. Continuity of care: Management of severe burns is long term, often taking months to years. Admission to a specialist center provides coordinated ongoing care from the initial resuscitation through to post-discharge rehabilitation. This continuity leads to the best functional and cosmetic outcomes.

7. Research and education: Burns centers are at the forefront of research into improved treatments like cultured epithelial autografts, engineered skin substitutes and scar therapies. They also provide education and professional development for healthcare staff in the care of burn injuries.

While initial assessment and resuscitation of a severe burn patient may take place at the nearest emergency department, early transfer to a specialist burns center is ideal to access dedicated facilities and multidisciplinary expertise which significantly improves survival rates and long term patient outcomes.

Q.criteria to admit the patient in burns unit ?

Criteria for admission to a specialized burn unit include:

1. Total body surface area (TBSA) burned: >10% TBSA partial thickness burns or >5% full thickness burns in adults. For children >5% TBSA burns of any depth. Severe burns requiring specialized care.

2. Facial burns: Any significant facial burns, especially those involving the eyes, nose, mouth or neck require admission for airway monitoring and specialized wound care.

3. Circumferential burns: Burns that wrap around extremities or the chest/abdomen require admission for possible escharotomy and intensive management.

4. Severe inhalational injury: Patients with signs of significant inhalation injury like burns inside the mouth/nose, singed nasal hairs, hoarseness of voice and respiratory distress need admission for airway support and monitoring.

5. Associated injuries: Patients with other injuries in addition to their burns such as fractures, internal organ damage or head injury require admission to a burn unit for holistic specialized care of all their injuries.

6. High voltage electrical burns: Patients with entry and exit wounds from high voltage electrical sources require close monitoring and fluid management in a burn unit due to the risk of internal organ damage and necrosis.

7. Chemical burns: Patients with chemical burns require admission for decontamination and neutralization of the chemical, as well as management of tissue damage which may continue beyond initial insult. Specialized care is needed.

8. Age extremes: Very young and very old patients have higher risk of morbidity and mortality from severe burns, due to fragile skin and higher risk of hypovolemic shock and infection respectively. Admission for close monitoring is usually required.

9. Smoke inhalation: Patients with signs of smoke inhalation like carbonaceous sputum, abnormal blood gases, chest X-ray changes or decreased level of consciousness require admission to burn unit for airway management, bronchodilators, high flow oxygen and ventilatory support.

10. Burn cause: Causes like flame burns, scald burns, contact burns, chemical burns and electrical burns each require different specialized forms of wound and injury management available only in dedicated burn units.

Q. How much burns this patient have?

Based on the information provided, the patient has:

– Second degree (partial thickness) burns on:

– Face

– Trunk (front and back) – 18% TBSA

– Left arm – 9% TBSA

– Both thighs – 18% TBSA (9% each thigh)

– Total known partial thickness burns = Face (9%) + Trunk (18%) + Left arm (9%) + Thighs (18%) = 54% TBSA

In addition, the patient has signs of inhalational injury:

– Soot in the nostrils

– Restlessness and difficulty breathing

Q. How will you manage this patient?

Given the >50% TBSA partial thickness burns, inhalational injury and need for airway management, this patient requires immediate resuscitation and admission to a specialized burn unit for the following care:

1. Maintain airway patency – endotracheal intubation and ventilation may be needed for respiratory compromise. Bronchodilators and suctioning to clear airway soot.

2. Aggressive IV fluid resuscitation to replace fluid losses from massive burn injuries. Using the Parkland formula, this patient requires:

– 4 x 70 kg (avg adult weight) x 54% TBSA = 15,120 mls or 15 liters IV fluid in the first 24 hours.

3. Analgesia and sedation – high dose IV opiates and sedatives will be required to control pain from the massive burns.

4. Escharotomy – may be needed if chest expansion becomes compromised, especially with inhalation injury. Burn surgeons to assess.

5. Infection control – strict isolation precautions, prophylactic antibiotics and antimicrobial dressings to prevent infection until burn wounds can be excised.

6. Nutrition – high protein and high calorie nutritional support will be needed to meet the demands of massive burn injuries and promote healing. Nasogastric feeding likely required.

7. Inhalational injury – 100% humidified O2, bronchodilators, steroids, chest physiotherapy and intubation/ventilation as needed based on blood gas analysis and arterial saturation levels.

8. Excision and skin grafting – once stabilized, the patient will undergo staged procedures to remove burned tissues (eschar) and apply skin grafts/substitutes to promote wound closure and minimize scarring.

9. Intensive rehabilitation – Physical and occupational therapy will be needed to minimize mobility/function impairment from massive tissue loss and prolonged immobilization.

Q. how will you manage his nutrition?

Severe burn patients have hypermetabolic needs due to increased cardiac output, catabolism, and wound healing requirements. It is essential to provide aggressive nutritional support to aid recovery. For this patient, the following nutritional management would be recommended:

1. Early enteral feeding: A nasogastric tube should be inserted as soon as possible to start enteral feeds. Oral intake will not meet the calorie and protein needs, and also damages the airway due to inhalational injury. Aim for feeding initiation within 6 hours of injury.

2. High calorie, high protein diet: The diet should provide 1.5-2 times the basal energy expenditure, which for a 70kg man is around 3500-4000 kcal/day. High protein with 1.5-2.5g/kg/day, around 100-150g/day for a 70kg man. Nutritional supplements and protein powders can be added to increase intake.

3. Specialized nutritional formulas: If available, specialized high energy and protein formulas for severe burn patients would be very beneficial and help limit additional supplementation. Formulas are available for both enteral tube feeding and oral supplemental drinks.

4. Monitor volume of nasogastric feeds: Feeds are usually started at 10-15ml/hour and advanced slowly every 4-6 hours as tolerated to a goal rate of 75-100ml/hour to achieve caloric targets. Frequent aspirates is needed to check for gastric emptying and tolerance. a strict fluid balance needs to be maintained.

5. Provide intravenous nutrition if enteral not possible: If nasogastric feeding is not tolerated, parenteral nutrition through a central venous catheter will be needed to prevent nutritional deficiencies developing rapidly. This will provide fat and glucose emulsions, amino acid solutions and electrolyte/mineral admixtures on an individualized basis.

6. Monitor nutrition closely: Daily weight, electrolyte levels, fluid balance, blood glucose, renal function, and liver function blood tests are required to monitor nutrition and look for deficiencies. Additional monitoring of triglyceride levels, albumin, prealbumin and CRP may also be needed. Calories/protein from all sources must be closely tracked.

7. Provide supplements as needed: Supplements of key factors like Vitamin C, Vitamin A, Zinc and Glutamine may be used in burn patients to promote wound healing, reduce muscle catabolism and support immunity. Trace elements Magnesium, Copper and Selenium may also needed in supplemented form.

8. Consult dietician: A dietician experienced in critical care burn nutrition should closely monitor this patient and adjust the nutrition plan as needed based on results of monitoring and the patient’s clinical progress. Dietary modifications or supplements will require dietician guidance.

1. Curreri formula: Used to calculate calories. Provides a multiplier based on %TBSA burned to determine total calories needed. For this patient with 54% TBSA burned:

Resting Energy Expenditure (REE kcal/day, 70kg male) = 70kg x 24kcal/kg/day = 1680kcal/day

Curreri formula:

REE x (1 + 1.5 x %TBSA burned)

So, 1680 x (1 + 1.5 x 54%) = 1680 x 3.81 = 6428 kcal/day total calorie needs

2. Toronto formula: Also used for determining calories. Tends to provide slightly higher requirements than Curreri formula.

Resting Energy Expenditure (same as above) = 1680kcal/day

Toronto formula:

REE x (1 + 2.3 x %TBSA burned)

So, 1680 x (1 + 2.3 x 54%) = 1680 x 4.122 = 6920 kcal/day total calorie needs

3. Protein needs: Severe burn patients require high amounts of protein for wound healing and combating catabolism. protein needs are:

Protein (g) = 1.5-2.5 g protein/kg body weight per day

So for 70kg man: 70kg x 2g protein/kg = 140g protein per day

4. Fluid requirements: Initially, fluid needs are calculated using the Parkland formula:

Fluid volume (mls in 24hrs) = 4mls x kg body weight x %TBSA burned

So, 4 x 70kg x 54% TBSA = 15,120mls or 15 liters of fluid in the first 24 hours.

Fluid rates then adjusted based on urine output monitoring, aiming for 0.5 to 1ml/kg/hr urine output in an adult. Daily weights also used to guide fluid balance management.

Q. What complications he can develop if not treated ?

Severe burn patients require prompt and intensive treatment to avoid life-threatening complications. Without proper treatment, this patient could develop:

1. Hypovolemic shock: Due to massive fluid losses from the burn wounds, shock can develop rapidly without prompt and aggressive fluid resuscitation. This can lead to organ failure and death.

2. Airway obstruction: With inhalational injury, progressive swelling of airway tissues can obstruct the airway, especially if an endotracheal tube is not placed prophylactically before swelling develops. This is a true emergency.

3. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Damage to the lungs from heat, smoke inhalation and respiratory inflammation leads to impaired gas exchange. Patients require intubation and mechanical ventilation to survive.

4. Wound Infection: Without appropriate anti-microbial measures, excision of necrotic tissues and skin coverage, massive burn wounds readily become colonized and infected. This can lead to septicemia and multi-organ dysfunction if not treated aggressively with IV antibiotics and surgical debridement/grafting.

5. Compartment Syndrome: Circumferential full thickness burns of extremities can lead to raised pressures within fascial compartments, impairing circulation. Fasciotomies are required urgently to prevent peripheral nerve and muscle damage.

6. Contractures: Without positioning, splinting, physical therapy and post-burn scarring/contracture release procedures, patients can develop severe joint contractures limiting mobility and function. Contractures become more severe and harder to treat the longer they develop.

7. Malnutrition and catabolism: Meeting the immense nutritional demands of massive burn injuries is challenging. Without adequate high calorie and protein intake, patients become malnourished, catabolic, and unable to heal wounds or fight infections. Supplementary nutrition must be started immediately.

8. Renal failure: Myoglobinuria, dehydration, sepsis and other issues can lead to acute tubular necrosis or multi-organ dysfunction syndrome causing renal failure in severe burn patients without close monitoring and treatment. Patients require dialysis to survive until renal function recovers.

9. Deep vein thrombosis: Prolonged immobility leads to high risk of DVTs and pulmonary emboli without prophylactic measures like compression stockings, pneumatic compression devices and administration of low molecular weight heparin.

10. Muscle contractures: Prolonged periods of immobility and catabolism lead to severe loss of muscle and development of contractures without positioning, physical therapy and nutritional support. Patients left unable to walk or function independently.

Q.Difference between partial and full thickness burns?

Partial thickness and full thickness burns differ in the depth of damage to the skin layers:

Partial (red/white, blistering,sensate) versus full thickness (white,leathery,desensate)

The clinical determinants of the depth are :

Presence of erythema: seen in superficial burns, Blisters

Texture: leathery skin seen with full thickness burns

Sensation: burns are painful in areas where there is no full thickness penetration

Partial thickness burns:

• Involve the epidermis and some portion of the dermis. The burn does not penetrate through the entire dermis.

• There are superficial partial thickness burns that involve only the epidermis and upper dermis. Deep partial thickness burns involve damage deeper into the dermis but not penetrating through it.

• Can be very painful due to nerve damage in the dermis. Sensation may be diminished in the center and most painful at the edges.

• Skin is usually reddened and blistered. Can take on a mottled appearance with pale, red and yellow areas indicating different depths.

• Usually heal within 2-3 weeks with minimal scarring as skin regeneration is still possible from remaining hair follicles and glands in the dermis. May require excision and grafting of deeper areas.

• Require same first aid as for full thickness burns including cooling, dressesing and analgesia. IV fluids and hospitalization usually needed for burns >10% TBSA.

Full thickness burns:

• Involve destruction of the entire epidermis and dermis, penetrating into subcutaneous fat or deeper structures. .

• Little or no pain as nerve endings have been completely destroyed. Surrounding or underlying tissue may still be painful.

• Appear white, brown or charred. Can be dry or leathery and waxy. Underlying fat or tissues may show through.

• Do not heal on their own and require excision and skin grafting for wound coverage and healing. Contractures and scarring form readily without grafting.

• Same first aid principles apply but prognosis more serious due to destruction of tissue and risks like infection, malnutrition, contractures and organ damage. Hospitalization always required, often in a burn unit.

• May take months to years of staged surgeries and rehabilitation to recover maximum function. Often life-changing injuries with significant disfigurement and disability.

Q. Formulas to determine burns percentage?

There are several formulas used to estimate the total body surface area (TBSA) involved in burns:

1. Wallace Rule of Nines: This allocates body areas into multiples of 9% based on surface area proportions.

– Head: 9%

– Chest: 9%

– Abdomen: 9%

– Upper/mid/low back and buttocks: 18%

– Each arm: 9%

– Each forearm: 1%

– Each hand: 1%

– Each thigh: 9%

– Each leg: 9%

– Each foot: 1% – Genitalia: 1%

You sum the percentages of the patient’s burned areas according to the rule of nines to estimate TBSA burned. For partial thickness burns, allocate either 4.5% or 9% for each area. For full thickness burns, always allocate 9% for each area.

2. Lund and Browder chart: This uses more precise surface area percentages based on the patient’s age. The chart allocates percentage values to various body parts which are then totaled to get TBSA burned. It considers the difference in body proportions between adults, children and infants. This tends to provide a more accurate TBSA estimation, especially in young patients.

3. Palmer rule: Uses the size of the patient’s palm to estimate surface area. The palm equals about 1% of the TBSA. So if 20 palmar surface areas are burned, that equates to about 20% TBSA. This is a very rough guide only.

Q. what happens to lung in inhalational injury and lung compliance?

Inhalational injury refers to damage to the respiratory tract and lungs from inhaling hot gases, toxic fumes or smoke. It often occurs in burn patients along with cutaneous burns and leads to:

1. Airway edema: Exposure to heat and chemicals causes inflammation and swelling of airway tissues like the mouth, throat, trachea and bronchi. This can rapidly obstruct the airway and requires prompt intubation in severe cases.

2. Loss of cilia: The tiny hair-like cilia in the airways are destroyed, impairing mucociliary clearance of debris and secretions. Patients develop increased mucus production leading to coughing, airway soiling and higher infection risk.

3. Bronchospasm: Irritant gases trigger bronchospasm and reactive airways disease like asthma, especially in those with smoke exposure. Bronchodilator therapy is often required.

4. Direct tissue damage: Chemicals and heat directly damage and destroy airway epithelial tissues. Sloughing of damaged cells obstructs airways and provides sites for bacterial colonization and infection.

5. Alveolar damage: Hot smoke and gases reach the alveoli, damaging the thin-walled aveoli. This impairs gas exchange, reducing lung compliance and efficiency. Damaged aveoli are prone to filling up with fluid (pulmonary edema), pus or blood.

6. Chemical pneumonitis: Inhalation of toxic gases like ammonia or chlorine leads to chemical pneumonitis with inflammation of lung parenchyma. There is pulmonary edema, reduced lung compliance, hypoxia and respiratory failure requiring ventilatory support.

In summary, inhalational injury significantly damages the lungs and respiratory tract through airway obstruction, loss of mucociliary clearance, bronchospasm, tissue destruction and chemical pneumonitis. This loss of lung function leads to reduced lung compliance, impaired gas exchange, increased secretions, high infection risk and often the need for intubation with mechanical ventilation to maintain respiration.

Management focuses on maintaining a patent airway, nebulized bronchodilators, chest physiotherapy, suctioning of airway secretions, high concentration O2, bronchoscopy to remove debris, and antibiotics in case of infection. Outcomes depend on the severity of lung injury and proper intensive management and monitoring in a burn unit.

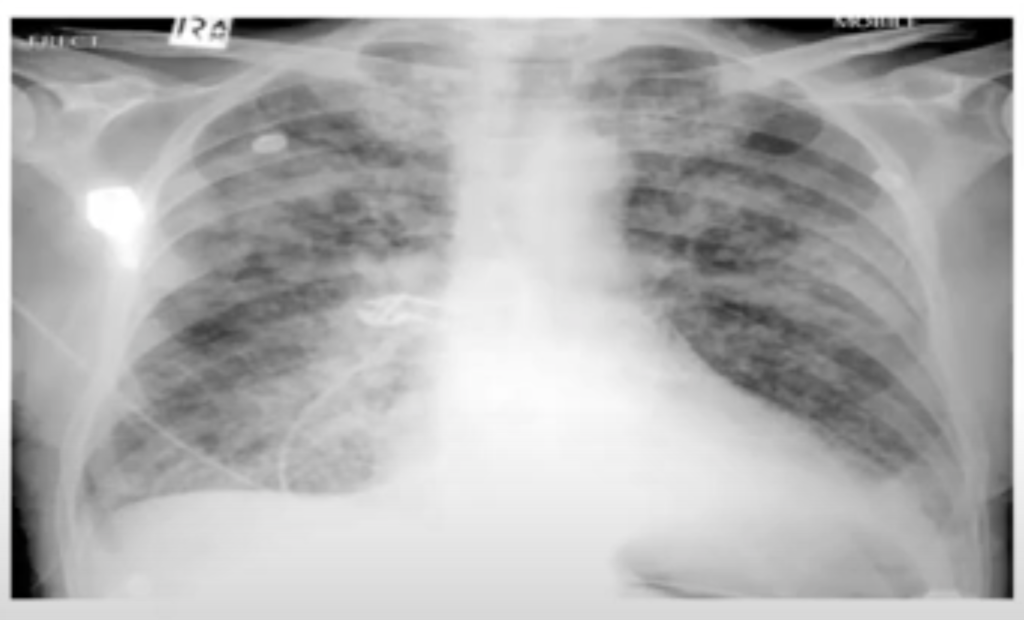

Q. What is this xray showing?

A useful approach for reading chest X-rays is the ABCDE mnemonic:

A – Airway: Look for tracheal deviation which can indicate tension pneumothorax. Swollen, indistinct carina can indicate inhalational injury.

B – Breathing ( lungs):

• Lung fields – Look for patchy or diffuse opacities (edema, pneumonitis, hemorrhage). Consolidation of lobes (pneumonia, aspiration). Areas of collapse (atelectasis).

• Pleura – Look for blurring of costophrenic angles (effusion). Pneumothorax causes sharp lucency between lung border and chest wall.

• Diaphragms – Clearly visible and at normal levels? If obscured can indicate free fluid e.g. hemothorax.

C – Circulation (mediastinum, heart):

• Mediastinum – Widened? Can indicate free air or fluid. Should have clear fat planes visible at the edges.

• Heart – Size and shape normal? Pulmonary edema causes enlarged heart, pneumothorax causes shift away from affected side. Pericardial effusion causes globular heart shape.

D – Bones and soft tissues:

• Ribs – Fractures, calluses or destructive lesions visible?

• Spine – Normal spine curvature? Scoliosis could affect lung inflation.

• Shoulders and clavicles – Inspect for signs of old or new fractures. Dislocation would narrow the chest

E – Everything else: Also inspect the lines, tubes, pacemakers, implanted devices and gastric tubes. Check correlation with the reported history and current concerns. Look behind the initial eye-catching findings.

Using this structured ABCDE approach helps ensure all areas of the CXR are systematically inspected. It reduces the risk of fixating on obvious findings while missing other subtle but important signs. Looking for both acute changes as well as pre-existing conditions provides important context for the current clinical scenario.

Combined with the 4 P’s mnemonic, following an ABCDE review of the CXR provides a thorough interpretation of lung pathology, complications and other mediastinal or bony abnormalities in burn patients – especially those with suspected or proven inhalational injury. Prompt and accurate CXR review is key to directing urgent treatment in these complex and unstable patients.

4 P’s of lung damage in burns:

1. Pulmonary edema: Appears as patchy or diffuse opacities in the lung fields, especially in dependent regions. Due to increased capillary permeability causing fluid shift into the alveoli. Requires diuretics, positioning and possible PEEP.

2. Pneumonitis: Diffuse opacities from inflammation/infection of lung parenchyma. May see air bronchograms. Requires antibiotics, bronchodilators and possible steroids. Usually due to smoke/chemical exposure.

3. Partial collapse: Loss of volume in all or part of a lobe. May have shift of mediastinum away from collapse. Requires bronchoscopy to remove debris plugging bronchus. At risk of secondary infection.

4. Pleural effusions: Blunting of costophrenic angles and loss of visibility of hemidiaphragm indicating fluid in the pleural space. Requires drainage using intercostal catheter to re-expand lung.

Other signs include:

• Peribronchial cuffing: Swelling along bronchial airways from inflammation.

• Atelectasis: Complete collapse of a lobe, appears dense on X-ray.

• Mediastinal widening: The mediastinum appears wide, often with loss of definition of borders. Due to inflammation and fluid.

• Pneumothorax: Visible lung edge with pleural air space. Life-threatening in ventilated patients and requires immediate chest drain insertion.

• Signs of ARDS: Diffuse bilateral infiltrates, Kerley B lines, wide mediastinum. Reflects non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema with severe lung injury.

• Tracheal deviation: Shift of trachea away from midline can indicate pneumothorax or collapse that requires drainage or bronchoscopy.

• Air bronchograms: Pockets of air visible within opacified lung segments, indicating patent bronchi surrounded by fluid, pus or inflammatory exudate.

Q. Fluid resuscitation in major burns?

Overview of fluid resuscitation in major burns. Some key points:

1. Parkland formula: For adults with >15% TBSA and children with >10% TBSA burns, the Parkland formula is used to calculate fluid requirements in the first 24 hours:

Volume (mls) = 4 x %TBSA x Body weight (in kg)

Half of this volume is administered in the first 8 hours, and the remaining half over the next 16 hours. This is a guide only, and fluid rates are then adjusted based on urine output and other parameters.

2. Inhalational injury or extensive burns may require additional fluid and also blood products to maintain volume status. Close monitoring is essential.

3. The Mount Vernon formula provides more gradual fluid administration over the first day divided into 6 hourly periods. Crystalloid or colloid solutions can be used. Blood transfusion is as indicated based on blood loss, hemoglobin levels and stability of vital signs.

4. insertion of a central venous catheter and urinary catheter is usually required for close monitoring in major burns. Urine output should be maintained at around 1ml/kg/hr as an indication of adequate end-organ perfusion.

5. Key adjuncts to fluid management include:

– Renal preservation: Maintaining renal perfusion using IV fluids based on urine output and CVP. Monitoring for rhabdomyolysis.

– Analgesia: IV opiates and nitrous oxide often required. Adequate pain control aids management of the hypermetabolic response.

– Temperature control: Strict warming to avoid hypothermia which exacerbates burn injury effects.

– GI prophylaxis: Antacids and H2 antagonists or PPIs to prevent GI ulceration and bleeding.

– Antibiotics: Prophylactic antibiotics are controversial. Only used for proven infection, not empirically.

– Nutrition: Early nutritional support, preferably via enteral feeding. Required to meet hypermetabolic demands and promote wound healing.

– Surgery: Escharotomy or emergency burn wound excision may be required if there is loss of chest wall movement or airway patency, or other critical circulation compromise.

Close monitoring and multidisciplinary team management in a burn unit is essential for major burns to optimize survival and avoid life-threatening complications.

Q.How to assess the adequacy of fluid therapy?

there are several key clinical parameters used to assess the adequacy of fluid resuscitation in major burns:

1. Peripheral warmth and capillary refill time (CRT): Well-perfused extremities indicate adequate central circulation. CRT < 2 seconds when radial pulse occluded indicates good peripheral perfusion. Pale, mottled or cyanosed extremities with prolonged CRT indicate poor perfusion requiring more aggressive fluid therapy.

2. Urine output (UO): Aiming for 0.5-1 ml/kg/hr in adults. UO > 30-50ml/hr indicates adequate renal perfusion. Falling UO < 30ml/hr indicates dehydration or inadequate circulation requiring increased IV fluids. Insertion of urinary catheter required to closely monitor UO.

3. Central venous pressure (CVP): CVP reflects circulating blood volume. Target is 0-8mmHg. CVP < 4 mmHg indicates possible hypovolemia requiring fluid bolus. CVP > 10-12 mmHg could indicate risk of fluid overload in absence of adequate urinary output. CVP trends also important.

4. Blood pressure: Adequate BP (e.g. > 90 mmHg systolic) does not necessarily indicate adequate tissue perfusion in burns. However, if systolic BP is low or difficult to maintain, this indicates significant volume depletion. Also monitor trends.

5. Pulse rate: Marker of intravascular volume status and tissue perfusion. Tachycardia > 120 bpm can indicate dehydration while a slow pulse < 60 bpm may signal overhydration. Monitor pulse rate trends.

6. Core temperature: Hypothermia < 36°C indicates impaired thermoregulation due to poor perfusion and reduces burn wound healing. Requires temperature control and may indicate under-resuscitation.

7. Hematocrit (Hct): As circulating volume increases due to IV fluids, Hct falls. A falling or even low Hct does not always indicate hemodilution or inflammation can increase fluid shifts into tissues. However, a slow decline in serial Hct levels over 6-8 hours of resuscitation can indicate adequate volume replacement. Rapid major drops in Hct can signal blood loss requiring transfusion.

8. Response to fluid challenges: If above parameters do not clearly indicate hypo/hypervolemia, a fluid challenge of 250-500mls of crystalloid over 30 mins may be given. An adequate BP rise > 10 mmHg, ↑ CVP > 2 mmHg, ↑ UO > 30mls/hr and improved perfusion/CRT indicates a fluid responsive state requiring more IV fluids. Lack of response could indicate need to trial other interventions e.g. inotropes, blood transfusion.

Q. Charcterised by / define/ what is ARDS ?

1. Severe acute lung injury: ARDS represents a severe inflammatory lung injury, usually secondary to a systemic insult such as sepsis, trauma, burn injury or acute pancreatitis. There is damage to the alveolar-capillary membrane causing pulmonary edema and impaired gas exchange.

2. Progressive and refractory hypoxemia: ARDS patients demonstrate worsening oxygenation despite supplemental oxygen. This is due to intrapulmonary shunting and ventilation-perfusion mismatch in the lungs. Hypoxemia is a cardinal feature of ARDS.

3. Diffuse bilateral pulmonary infiltrates: Chest x-ray shows bilateral opacities representing pulmonary edema fluid, inflammation and atelectasis. Lung scapacity is reduced. Distribution is usually bilateral and patchy or diffuse.

4. Non-cardiogenic: Pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP) is normal or low, indicating the pulmonary edema is not due to left heart failure. Caused by damage to the lungs themselves, not excess fluid volume.

5. Reduced lung compliance: Stiff, poorly compliant lungs require higher inflation pressures to open alveoli, but some remain closed or fluid-filled. This results in ventilation-perfusion mismatch and shunting.

6. Ventilation-perfusion mismatch: Some alveoli remain open and well-perfused while others are flooded or collapsed, causing impaired gas exchange. Perfusion of non-ventilated or poorly ventilated alveoli leads to shunting of blood past the lungs.

Other features include:

– Severe dyspnea requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation.

– Ground glass appearance on lung CT scans.

– Impaired lung mechanics e.g. reduced functional residual capacity and lung volumes.

– Risk of barotrauma due to high inflation pressures required. Pneumothorax may develop.

– Prone to secondary infections and sepsis without proper treatment.

– High mortality especially in late ARDS. Improved with lung-protective ventilation, dialysis, nutritional support and treatment of underlying conditions.

ARDS represents a medical emergency with a complex pathology and high mortality. Accurate diagnosis based on clinical and radiological findings along with other potential causes of respiratory failure and bilateral pulmonary infiltrates is key to early optimal treatment and improved outcomes.

Q.major causes of ARDS ?

Direct (pulmonary) causes:

• Inhalation injury: Inhalation of toxic gases, smoke or chemical fumes directly damages the lungs. Common in burn patients.

• Aspiration pneumonitis: Inhalation of gastric contents into the lungs causes chemical pneumonitis and inflammation.

• Near drowning: Inhalation of water into the lungs leads to surfactant disruption, alveolar collapse and pulmonary edema.

• Chest trauma: Lung contusion or other thoracic injuries damage the lungs directly.

• Pneumonia: Severe bacterial or viral pneumonia can directly progress to ARDS, especially in susceptible individuals.

Indirect (systemic) causes:

• Sepsis: Severe systemic infection or septicemia releases cytokines triggering systemic inflammation and increased capillary permeability in the lungs.

• Major trauma: Multiple fractures, head injury or damage to other organs releases inflammatory mediators that secondarily induce ARDS.

• Severe burns: >30-40% TBSA burns cause systemic inflammation and fluid shifts that damage the lungs, even without direct inhalation injury.

• Acute pancreatitis: Inflammation and enzyme release severely damages tissues and circulatory system, indirectly impacting the lungs.

• Blood transfusion: Transfusion of multiple units of packed red cells over a short time in a susceptible patient can trigger TRALI – transfusion related acute lung injury. Due to donor antibodies.

• Cardiopulmonary bypass (CABG) surgery: The artificial pump-driven circulation during open heart surgery can trigger inflammation subsequently damaging the lungs.

• Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC): Widespread microvascular thrombosis causes organ damage, reduced oxygenation and ARDS. Usually secondary to another condition e.g. sepsis, trauma, obstetric complications.

In many cases, ARDS develops from a combination of direct and indirect lung insults e.g. Smoke inhalation, burn injury and sepsis in a patient with pre-existing lung disease. The common mechanism is an exaggerated inflammatory response that disrupts the alveolar-capillary interface, impairs surfactant and causes pulmonary edema.

Q. Management of ARDS?

1. ABCDE and assess underlying cause. Investigate fully. Take a history and physical exam to determine predisposing factors.

2. Oxygen therapy to maintain SpO2 >90%. Escalate to mechanical ventilation as required. Discuss early with anesthesiologist and physiotherapist for intubation and ventilation strategies.

3. Keep lungs dry – fluid restriction required once initial resuscitation complete. Monitor fluid balance closely. Diuretics if fluid overloaded.

4. Treat complications like infection, organ failure, DIC aggressively and early.

5. Mechanical ventilation:

• Low tidal volume (6mls/kg) to avoid barotrauma.

• Moderate PEEP to prevent atelectasis while limiting overdistension.

• Permissive hypercapnia – higher PaCO2 accepted to minimize lung damage.

• Inverse ratio ventilation – prolong inspiratory time to improve oxygenation.

• Prone positioning – improves ventilation-perfusion matching.

• Physiotherapy – essential for secretion clearance and management.

6. High frequency oscillatory ventilation for severe refractory hypoxemia – provides very small tidal volumes at fast rates as a rescue measure.

7. ECMO for profound life-threatening hypoxemia – high risk but used as a last resort when all else fails. Oxygenates blood outside the body.

8. Steroids – controversial and risks outweigh benefits in most cases. May be used in inflammation-dominant ARDS at some centers. Monitor side effects closely.

9. Inotropic and pulmonary vasodilator therapy – to support circulation and reduce pulmonary artery pressures. Improves flow through ventilated lung regions. inhaled nitric oxide/prostacyclin – pulmonary vasodilation

10. Nutrition:

• Enteral feeding preferred after 48-72 hours of intubation. Provides nutrition and reduces catabolism.

• Parenteral nutrition if unable to feed enterally. Essential for recovery and weaning.

A multidisciplinary intensive approach with close monitoring provides the greatest opportunity for surviving ARDS. However, mortality remains high especially in late or prolonged ARDS. Supportive management of complications and underlying conditions are key to weaning and recovery. Ongoing research continues to improve future management.

Q. Berlin Criteria for ARDS.?

The Berlin criteria define 3 categories of ARDS severity based on the degree of hypoxemia:

• Mild ARDS:

– Timing: Within 1 week of known clinical insult or new/worsening respiratory symptoms.

– Chest imaging: Bilateral opacities consistent with pulmonary edema.

– Origin of edema: Respiratory failure not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload.

– Oxygenation (with PEEP ≥5 cm H2O):

– 200 mmHg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg

• Moderate ARDS:

– Timing: Within 1 week of known clinical insult or new/worsening respiratory symptoms.

– Chest imaging: Bilateral opacities consistent with pulmonary edema.

– Origin of edema: Respiratory failure not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload.

– Oxygenation (with PEEP ≥5 cm H2O):

– 100 mmHg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 mmHg

• Severe ARDS:

– Timing: Within 1 week of known clinical insult or new/worsening respiratory symptoms.

– Chest imaging: Bilateral opacities consistent with pulmonary edema.

– Origin of edema: Respiratory failure not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload.

– Oxygenation (with PEEP ≥5 cm H2O):

– PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 100 mmHg

Other criteria:

• Respiratory failure not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload. Requires objective assessment to exclude hydrostatic pulmonary edema.

• Acute onset: Within 1 week of known clinical insult (pneumonia, aspiration, trauma) or new/worsening respiratory symptoms.

• Chest imaging (radiograph, CT scan, or lung ultrasound): Bilateral opacities not fully explained by pleural effusions, lobar/lung collapse, or nodules.

• Need for PEEP ≥5 cm H2O (or non-invasive ventilatory support) to maintain PaO2 ≥60 mmHg or peripheral oxygen saturation ≥90% on supplemental O2.

• If PaO2/FiO2 ratio cannot be measured due to inability to obtain ABG or patient factors, SpO2/FiO2 ratio ≤315 suggests ARDS in mechanically ventilated patients (100% O2, PEEP ≥5cmH2O).

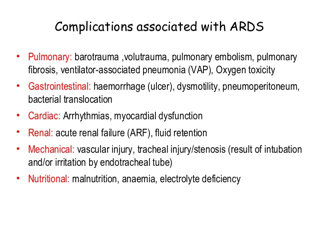

Q. Complications of ARDS?

Q. clinically and radiological differences between pulmonary oedema Vs. ARDS.?

Here are the key differences between pulmonary edema and ARDS:

Clinical features:

• Onset: Pulmonary edema develops over days to weeks, ARDS is acute within 7 days of an insult.

• Underlying cause: Pulmonary edema is due to left heart failure or fluid overload. ARDS is due to direct (e.g. pneumonia) or indirect (e.g. sepsis) lung injury and not primarily due to excess fluid.

• Orthopnea and PND: Typically present in pulmonary edema, less prominent in ARDS.

• Chest pain: More common in pulmonary edema due to pulmonary venous hypertension. Usually absent in ARDS.

• Pulse oximetry: Typically remains >90% in pulmonary edema, often <90% in ARDS due to shunting and ventilation-perfusion mismatch.

• Crepitations: Commonly coarse in pulmonary edema, often fine in ARDS.

• Chest movement: May be asymmetric in ARDS due to areas of collapse or consolidation. Usually symmetric in pulmonary edema.

• Response to diuretics: Improves rapidly in pulmonary edema. Limited improvement in ARDS as excess fluid is not the primary issue.

Radiological features:

• Pulmonary venous congestion: Prominent in pulmonary edema, not a major feature of ARDS.

• Cardiomegaly: Typically present in pulmonary edema, usually normal heart size in ARDS.

• Pleural effusions: Often larger and bilateral in pulmonary edema. Usually absent or small in ARDS.

• Distribution of opacities: Perihilar or batwing pattern in pulmonary edema, diffuse and patchy in ARDS.

• Vessel size: Pulmonary veins enlarged centrally in edema, not in ARDS.

• Time course: Rapid resolution of opacities with treatment of pulmonary edema. Slower improvement in ARDS as underlying lung injury takes longer to recover from.

• Unilateral opacities: Can represent pneumonia, aspiration, lung collapse in ARDS. Usually bilateral changes in pulmonary edema.

• Ground glass opacities: More prominent in ARDS, representing damaged, leaky alveoli and interstitial inflammation. Less marked in pulmonary edema.

In summary, the clinical and radiological features reflect the underlying pathological processes – left heart failure and fluid overload in pulmonary edema versus acute inflammatory lung injury in ARDS. Treatment options also differ significantly. Accurate diagnosis is key to optimal management and outcomes.

Q. What are the long term sequelae of ARDS?

1. Pulmonary function impairment: ARDS causes damage to the alveolar-capillary interface, surfactant depletion and lung inflammation. This results in mild to moderate restrictive lung disease and reduced diffusion capacity in survivors. Pulmonary function often improves over 6-12 months but rarely returns to normal. Some patients may require long term oxygen therapy.

2. Neurocognitive dysfunction: ARDS survivors frequently experience problems with memory, concentration, problem solving and weakness. This is partly due to critical illness myopathy from medications/ventilation and also due to hypoxemia and micro-emboli damaging the brain. Cognitive rehabilitation and physical therapy can help with gradual recovery.

3. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): The experience of severe respiratory distress, sedation, delirium and prolonged ICU admission can contribute to symptoms of PTSD like nightmares, flashbacks, anxiety and depression in some survivors. Counseling and support groups may be beneficial.

4. Physical debility: Prolonged mechanical ventilation, sedation and ICU admission result in severe deconditioning and muscle weakness. Patients require intensive physical rehabilitation and re-training for activities of daily living before discharge home. Many are unable to return to work due to physical limitations.

Other issues that may persist long term include:

• Swallowing dysfunction and need for enteral feeding. Speech therapy is often required.

• Higher risk of re-hospitalization especially in the year following discharge from the ICU. Patients need close follow up and management of chronic medical issues.

• Impaired quality of life: Problems with mobility, daily activities, relationships and return to work significantly impact quality of life and place strain on patients and their caregivers.

• Secondary organ impairment: ARDS can lead to temporary or long term damage of organs like the kidneys, heart and liver due to poor perfusion, inflammation or complications such as sepsis. Some patients may require ongoing specialist management.

Most ARDS survivors experience gradual improvement over 6-24 months with rehabilitation and support. However, residual long term physical and psychological consequences are common and may be severe in some cases, especially as severity and duration of the ICU admission increase. A multidisciplinary approach to rehabilitation and follow up care offers the best opportunity for regaining function and improving quality of life after this critical illness.

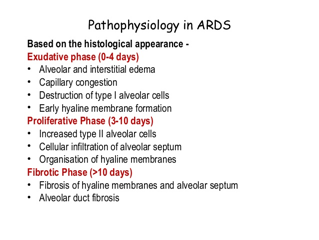

Q. Pathophysiology ARDS ?

1. Acute exudative phase: Usually lasts around 1 week. Characterized by:

• Damage to the alveolar-capillary membrane: The basement membrane is disrupted leading to increased permeability and leakage of protein-rich fluid into the interstitium and alveoli. Cytokines like IL-1, IL-6, IL-8 are released triggering an inflammatory cascade.

• Neutrophil migration and activation: Neutrophils migrate into the lungs and release proteases and reactive oxygen species that cause further damage.

• Pulmonary edema: Fluid from the damaged capillaries leaks into the alveoli and interstitium, causing stiff, poorly compliant lungs. Hypoxemia develops due to shunting and V/Q mismatch.

• Atelectasis and loss of surfactant: Alveoli collapse and surfactant function is impaired, contributing to reduced lung volumes and compliance.

• Diffuse alveolar damage: The alveolar epithelium is disrupted with hyaline membranes depositing in the airspaces. Fibrin clots may form.

2. Fibroproliferative phase: Begins around day 7-14. Characterized by:

• Activation of fibroblasts: In an attempt to repair the initial damage, fibroblasts proliferate and deposit collagen, fibronectin and proteoglycans.

• Scar formation: Disordered collagen deposition can lead to scarring of the lungs with reduced compliance and volumes. Persistent shunting and hypoxemia.

• Resolution: In many patients, the normal reparative processes resolve the fibrosis over weeks to months and lung function gradually recovers. Residual scarring may remain.

• Progression to fibrosis: In some cases, uncontrolled persistent fibroproliferation leads to extensive scarring and progressive fibrosis with honeycombing. Irreversible changes and significant morbidity. Known as ARDS associated pulmonary fibrosis. Treatment options are limited.

Q. Pain management in burns as per who ladder?

Pain management in burn patients is extremely important for humanitarian and clinical reasons. The WHO analgesic ladder provides a stepwise approach for managing pain in burns:

Step 1: Non-opioid drugs ± adjuvant analgesics

For mild to moderate pain:

• Paracetamol: 15-20 mg/kg PO/PR q4-6h. Maximum 60-75 mg/kg/day.

• NSAIDs: Ibuprofen 400-600mg PO q6-8h. Avoid if renal failure or GI bleed risk.

• Gabapentin: For neuropathic pain. Start 100-300 mg PO at night, titrate up to 1800 mg/day.

Step 2: Opioid for moderate to severe pain ± non-opioid ± adjuvant

• IV Morphine: 0.05-0.2 mg/kg IV bolus, then 0.05 mg/kg IV q2h. Increase dose by 25% if pain uncontrolled.

OR

• IV Fentanyl: 0.5-2 mcg/kg IV, then 0.5-1mcg/kg IV q30min-2h. Up to maximum 7-10 mcg/kg/h.

• Consider ketamine infusion for severe background or procedural pain: Start 0.1-0.3 mg/kg/h, up to 4 mg/kg/h.

• Adjuvants: Consider clonidine, dexmedetomidine with opioids to improve sedation and pain control.

Step 3: Interventional analgesics ± non-opioid ± opioid ± adjuvant

For severe background, neuropathic or incident pain:

• Regional anesthesia: IVRA, Bier’s block, epidural anesthesia. Provides profound analgesia but high risk in massive burns or sepsis.

• Nurse-controlled analgesia or patient-controlled analgesia using morphine or fentanyl.

• Ketamine Infusion: As in Step 2. Useful for dressing changes/physiotherapy.

• Consider intercostal nerve block, paravertebral block for chest wall burns. High risk in some patients.

• Intrathecal fentanyl: 10-25 mcg bolus, effective for days. High risk, mainly used in experienced centers.

Other key principles:

• Regular scheduled analgesia and pre-emptive dosing prior to procedures. “As required” not appropriate.

• Two or more analgesic modalities often required, depending on extent of injury.

• Ongoing assessment using age-appropriate pain assessment tools. Patient feedback essential.

• Treat anxiety, fear and distress which exacerbate pain. Consider anxiolytics, relaxation techniques.

• Enteral paracetamol or certain opioids may be preferred when IV access lost. However, variable absorption.

• Once stabilized and oral intake resumed, WHO ladder still applies to transition to oral analgesia.

Q. how would you prevent hypothermia in burns?

Hypothermia is a serious risk in major burn patients and preventing heat loss is crucial. Here are key measures to prevent hypothermia in burns:

1. Fluid resuscitation: Rapid and adequate fluid replacement helps maintain core temperature. Formulae like the Parkland formula (4 ml LR x %TBSA burn) guide initial fluid volumes required. Urine output, CVP and other parameters help determine ongoing fluid needs.

2. Reduce heat loss:

• Remove wet clothing and jewelry. Dry the patient fully.

• Cover the burn wound and unburned areas with dry sheets and blankets.

• Use a radiant warmer or forced warm air device. Keep room temperature at 28-32°C.

• Consider polyurethane burn dressings which provide an insulated barrier.

• Place heat packs, warm blankets or mattresses under and around the patient.

• Cover the patient’s head to reduce heat loss from the head and neck.

3. Increase heat production:

• Shiver prevention: Provide analgesia to prevent shivering which increases metabolic demands. Opioids are often required for shiver prevention in larger burns.

• external rewarming: Apply forced air warming blanket. Chemical heat packs can also be used.

• warmed IV fluids: Use fluid warmers for rapid infusions. Aim for 38-40°C.

4. Monitoring temperature:

• Core temperature (esophageal or rectal probe) should be continuously monitored.

• A fall in temperature <36°C indicates impaired thermoregulation – more aggressive rewarming required.

• Temperature is especially likely to drop during the first 24 hours, during resuscitation, anesthesia and surgery. Close monitoring and anticipation of heat loss crucial at these times.

5. Other factors:

• Early referral to a burn unit as they are specially equipped to prevent hypothermia.

• Intubated patients lose heat via the endotracheal tube – minimize ventilation and use a heat and moisture exchanger.

• Early excision and closure of full thickness burn wounds helps reduce fluid and protein loss. Escharotomy may be required for circumferential burns.

• Nutritional support helps generate heat and maintain core temperature. Enteral feeding should be started early when possible.

• In severe cases, extracorporeal rewarming may be required in addition to the above measures. This may involve venovenous rewarming or cardiopulmonary bypass.

Maintaining normothermia is vital to survival and outcomes in major burns.