Skull Base Anatomy

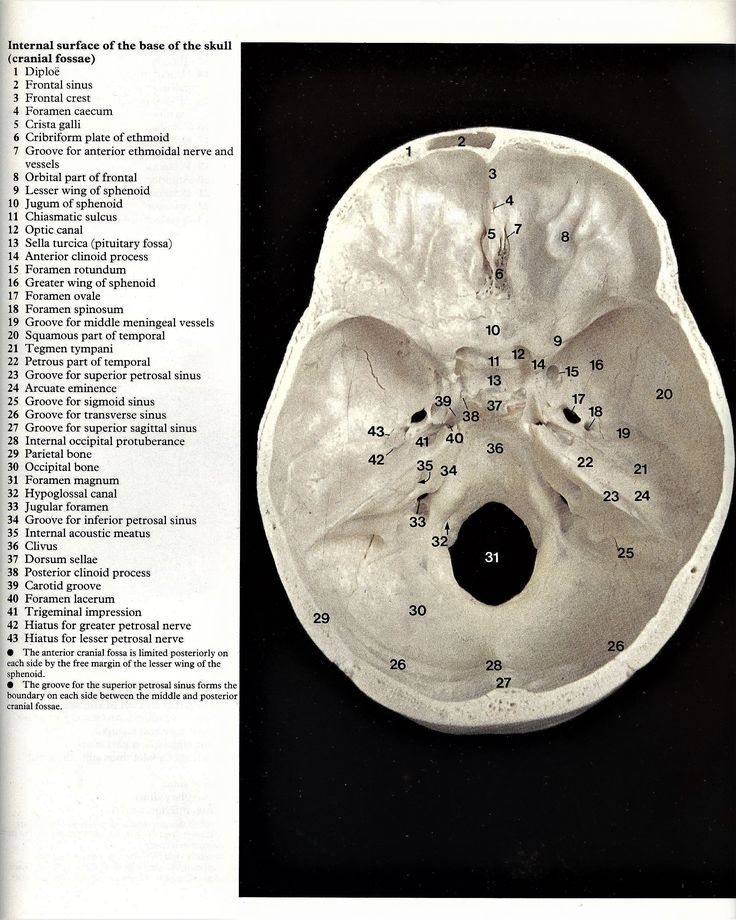

Q. Base of skull is divided into how many fossas?

The base of the skull is divided into three fossae (plural of fossa):

– Anterior cranial fossa

– Middle cranial fossa

– Posterior cranial fossa

The anterior cranial fossa forms the floor of the anterior cranial cavity. The middle cranial fossa constitutes the central basal part of the skull. The posterior cranial fossa forms the floor of the posterior cranial cavity and houses the cerebellum, brainstem and cranial nerves.

Q. Boundaries of these fossas?

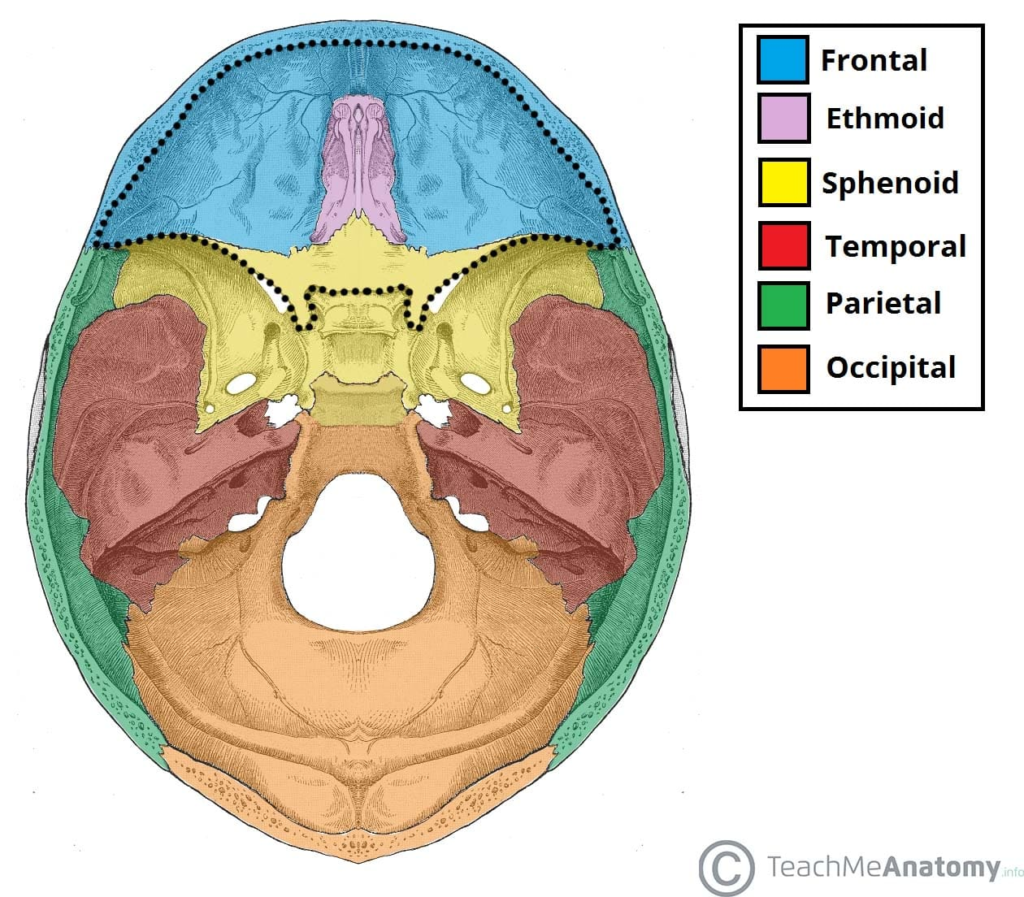

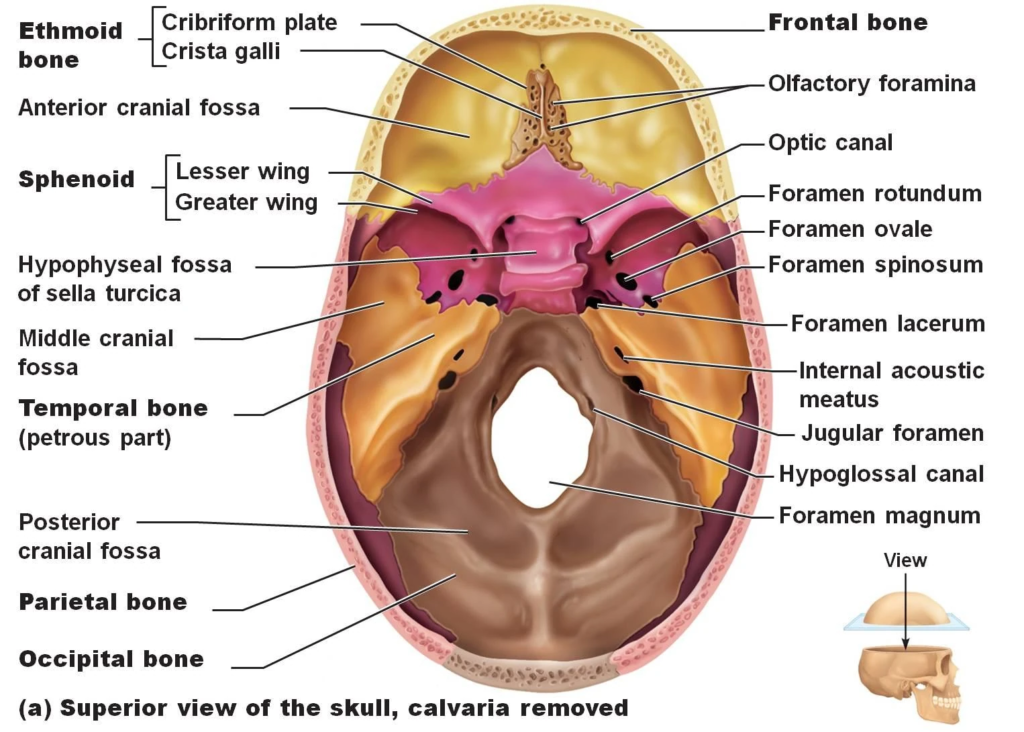

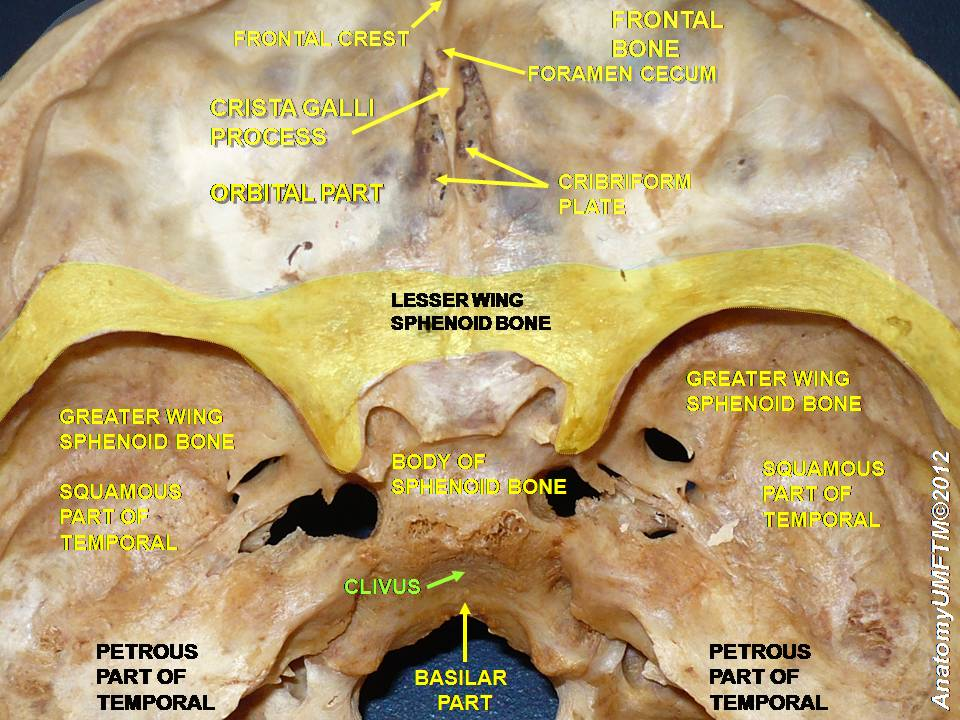

The anterior cranial fossa consists of three bones: the frontal bone, ethmoid bone and sphenoid bone.

- Anteriorly and laterally it is bounded by the inner surface of the frontal bone.

- Posteriorly and medially it is bounded by the limbus of the sphenoid bone. The limbus is a bony ridge that forms the anterior border of the prechiasmatic sulcus (a groove running between the right and left optic canals).

- Posteriorly and laterally it is bounded by the lesser wings of the sphenoid bone (these are two triangular projections of bone that arise from the central sphenoid body).

- The floor consists of the frontal bone, ethmoid bone and the anterior aspects of the body and lesser wings of the sphenoid bone

The middle cranial fossa consists of three bones – the sphenoid bone and the two temporal bones.

Its boundaries are as follows:

- Anteriorly and laterally it is bounded by the lesser wings of the sphenoid bone. These are two triangular projections of bone that arise from the central sphenoid body.

- Anteriorly and medially it is bounded by the limbus of the sphenoid bone. The limbus is a bony ridge that forms the anterior border of the chiasmatic sulcus (a groove running between the right and left optic canals).

- Posteriorly and laterally it is bounded by the superior border of the petrous part of the temporal bone.

- Posteriorly and medially it is bounded by the dorsum sellae of the sphenoid bone. This is a large superior projection of bone that arises from the sphenoidal body.

- The floor is formed by the body and greater wing of the sphenoid, and the squamous and petrous parts of the temporal bone.

The posterior cranial fossa is comprised of three bones: the occipital bone and the two temporal bones.

It is bounded as follows:

- Anteromedial – dorsum sellae of the sphenoid bone (large projection of bone superiorly that arises from the body of the sphenoid).

- Anterolateral – superior border of the petrous part of the temporal bone.

- Posterior – internal surface of the squamous part of the occipital bone.

- Floor – mastoid part of the temporal bone and the squamous, condylar and basilar parts of the occipital bone.

Q. contents of these fossas?

Here are the key contents found in the cranial fossae at the base of the skull:

Anterior Cranial Fossa:

– Frontal lobe of cerebrum

– Olfactory bulbs

– Optic chiasm

– Optic nerves (CN II)

– Anterior cerebral arteries

– Anterior parts of circle of Willis

Middle Cranial Fossa:

– Temporal lobe of cerebrum

– Pituitary gland

– Chiasmatic cistern

– Cavernous sinus

– Internal carotid arteries

– Oculomotor nerve (CN III)

– Trochlear nerve (CN IV)

– Trigeminal nerve (CN V)

– Abducent nerve (CN VI)

Posterior Cranial Fossa:

– Cerebellum

– Brainstem (midbrain, pons, medulla)

– Fourth ventricle

– Cranial nerves (VII-XII)

– Vertebrobasilar system

– Venous sinuses – sigmoid, transverse, occipital

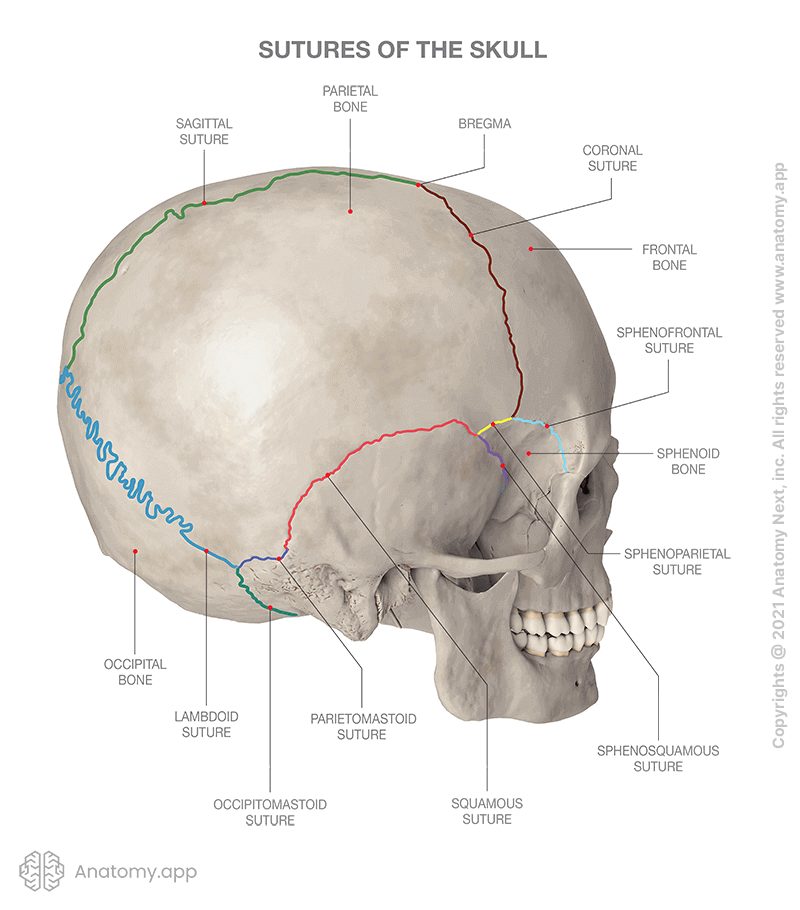

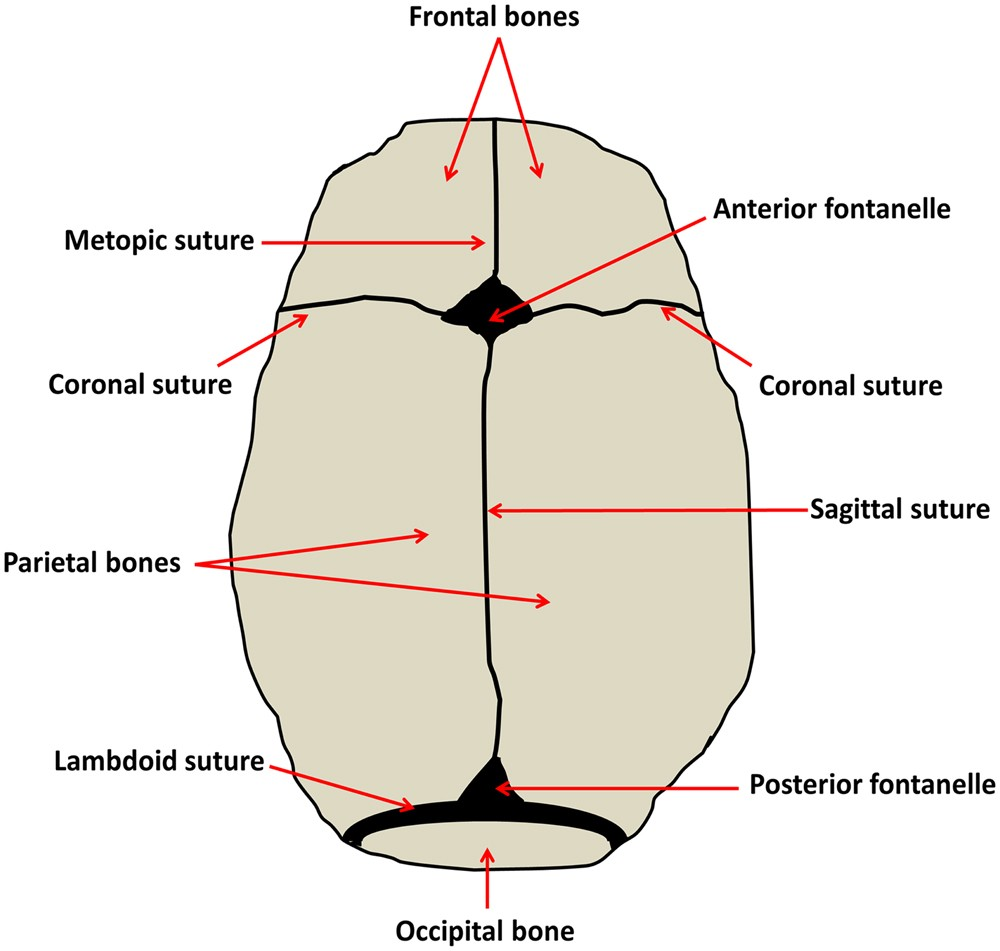

Here are the major sutures found in the skull:

– Coronal suture – Joins the frontal bone to the two parietal bones.

– Sagittal suture – Joins the two parietal bones together down the midline.

– Lambdoid suture – Joins the two parietal bones to the occipital bone posteriorly.

– Squamous suture – Joins the temporal and parietal bones.

– Sphenofrontal suture – Between the sphenoid bone and the frontal bone.

– Sphenoparietal suture – Between the sphenoid bone and the parietal bones.

– Sphenosquamous suture – Between the sphenoid and temporal bones.

– Sphenopetrosal suture – Between the sphenoid bone and the petrous part of the temporal bone.

– Pterion – Junction between the frontal, parietal, sphenoid and temporal bones.

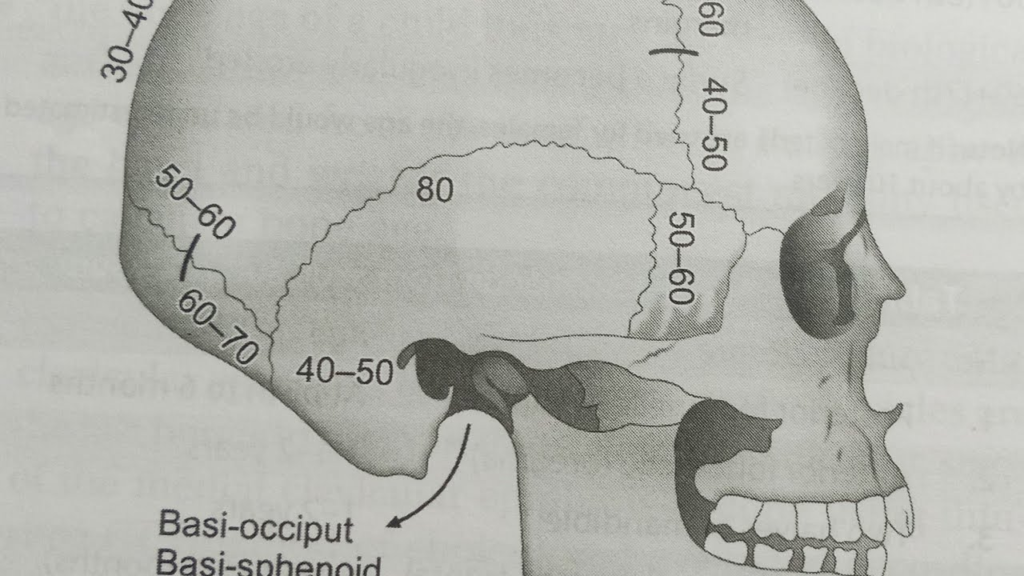

Q.age they fuse ?

– Sagittal suture: Fuses between 22-24 years of age.

– Coronal suture: Fuses between 24-26 years of age.

– Lambdoid suture: Fuses between 26-29 years of age.

– Squamous suture: Fuses around 30 years of age.

– Sphenofrontal suture: Fuses around 40-50 years of age.

– Sphenoparietal suture: Fuses around 40-60 years of age.

– Sphenosquamous suture: Fuses around 30-40 years of age.

– Sphenopetrosal suture: Fuses around 25-30 years of age.

So in general, the suture fusion timeline progresses from anterior to posterior with the sagittal sutures fusing first followed by the coronal and lambdoid sutures. The squamous suture is an exception fusing earlier. The sphenoid bone sutures are the last to fuse as adults around 40-60 years.

If the cranial sutures fuse prematurely at birth, it is called craniosynostosis.

Some key points about craniosynostosis:

– Results in abnormal skull growth and shape.

– Can involve one suture (simple craniosynostosis) or multiple sutures (complex craniosynostosis).

– Common types include sagittal, coronal, metopic, and lambdoid craniosynostosis depending on which suture(s) fuse early.

– Can occur as an isolated defect or as part of a genetic syndrome.

– Caused by premature fusion of the fibrous sutures between skull bones.

– Normal suture closure occurs progressively in childhood/adulthood, not at birth.

– Can result in elevated intracranial pressure, impaired brain growth.

– Treated by surgery to reopen the fused sutures and remold the skull. Best done early.

– If left untreated, can cause functional impairments and cognitive deficits.

Q. Type of joint ?

The sutures of the skull are a type of fibrous joint called synarthroses. More specifically, they are sutures – bones connected by short fibers of Sharpey’s fibers.

Some key features of sutures as synarthroses:

– Immovable joints that allow very little or no movement between the bones.

– United by dense fibrous connective tissue between the bones.

– Sharpey’s fibers anchor the bones together.

– Found in the skull and teeth sockets to firmly unite bones.

– Allow only slight flexibility and growth between skull bones.

– Distinct from synostoses which are bony unions between bones with no joint cavity.

– Distinct from synovial joints that allow free movement between bones.

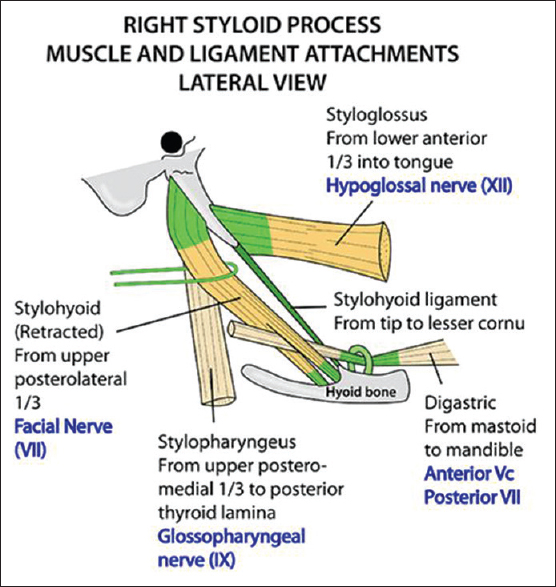

The styloid process is a slender pointed bony projection located on the temporal bone of the skull. Here are the main muscles that attach to the styloid process:

– Styloglossus muscle – Arises from the styloid process and allows upward and backward motion of the tongue.

– Stylohyoid muscle – Arises from the styloid process and elevates the hyoid bone during swallowing and speaking.

– Stylopharyngeus muscle – Arises from the styloid process and elevates the pharynx during swallowing and speech.

– Stylohyoid ligament – Extends from the tip of the styloid process to the lesser cornu of hyoid bone. Provides anchorage for the hyoid bone.

– Tensor veli palatini muscle – Hooks around the styloid process as it descends from the cartilage of the auditory tube to the palate.

– Lateral pterygoid muscle – Originates from the pterygoid process and partially inserts onto the styloid process. Opens the jaw.

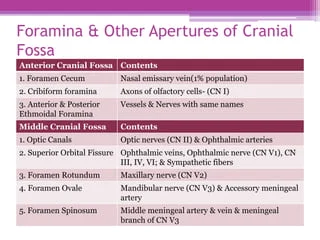

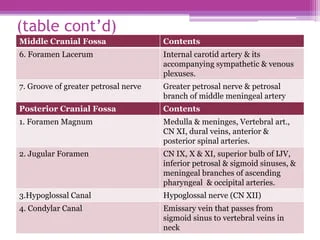

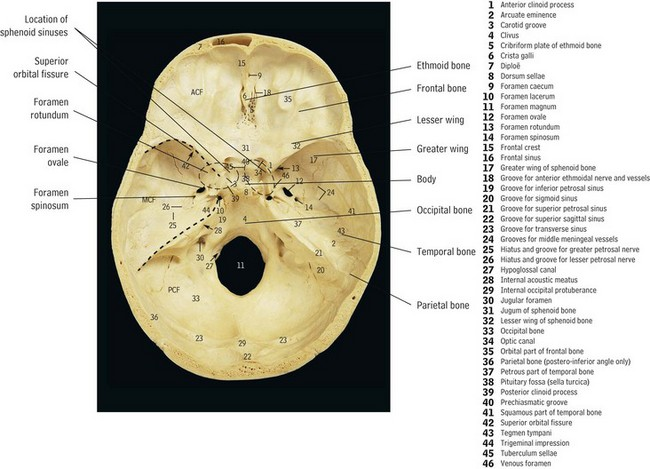

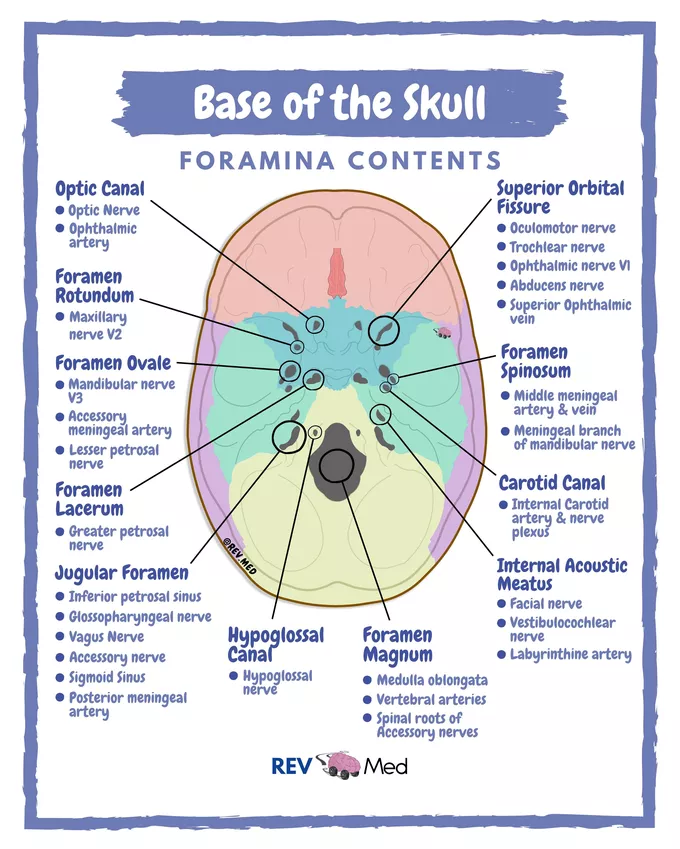

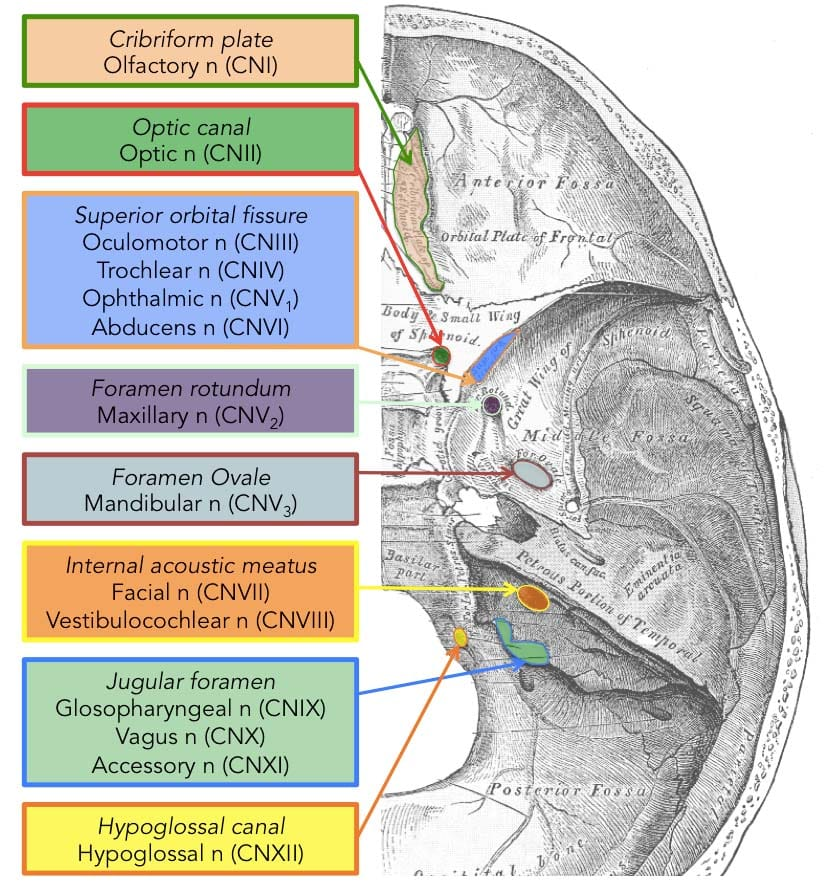

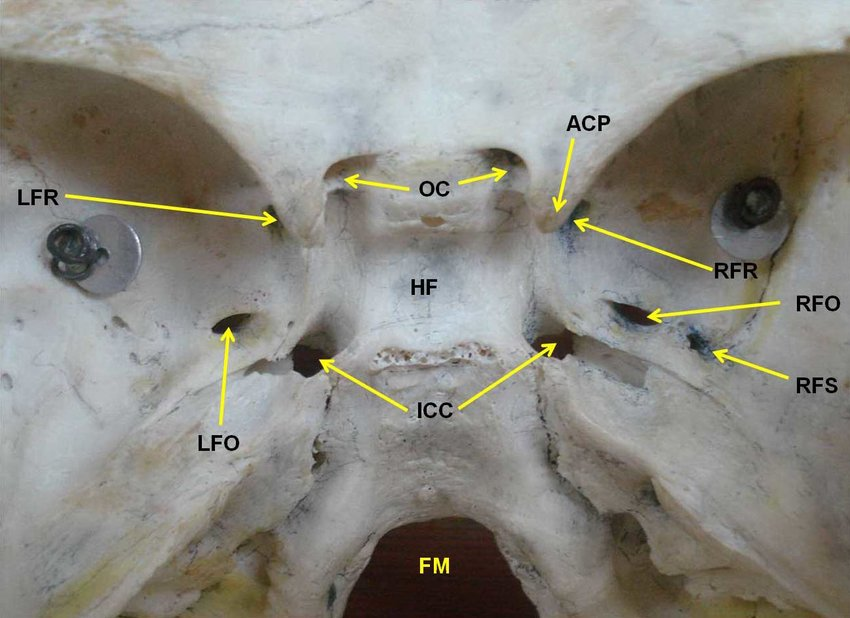

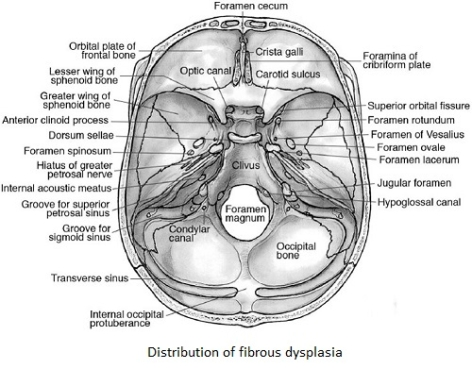

Here are the main cranial foramina categorized by which fossa they are located in:

Anterior Cranial Fossa:

– Foramen cecum

– Olfactory foramina

Middle Cranial Fossa:

– Optic canal

– Superior orbital fissure

– Foramen rotundum

– Foramen ovale

– Foramen spinosum

– Carotid canal

Posterior Cranial Fossa:

– Internal acoustic meatus

– Jugular foramen

– Hypoglossal canal

– Foramen magnum

Q.causes of lytic skull lesions?

Some common causes of lytic (bone destroying) lesions in the skull include:

– Metastatic cancer – Metastases to the skull from lung, breast, prostate, thyroid, kidney cancers are most common. Seen on imaging as rounded lytic lesions with loss of normal bone architecture.

– Multiple myeloma – Malignant plasma cell disorder that can cause “punched-out” lytic bone lesions in the skull.

– Langerhans cell histiocytosis – Rare disorder that can cause multiple lytic skull lesions, particularly in pediatric patients.

– Fibrous dysplasia – Benign disorder causing expansion and thinning of areas of the skull, seen as ground-glass lytic lesions on x-ray.

– Osteomyelitis – Bacterial or fungal infection of the bone can lead to lytic destruction and erosions of the skull.

– Paget’s disease of bone – Chronic disorder that can cause scattered areas of increased bone turnover and lytic lesions in the skull.

– Primary bone cancers like osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma – Very rare in the skull but can appear as aggressive lytic lesions.

– Metabolic disorders like hyperparathyroidism – Can cause generalized bone loss and lytic changes.

Q. Structures passing through carotid canal?

The carotid canal is a bony canal located within the petrous part of the temporal bone in the skull. It contains the internal carotid artery and associated sympathetic nerves.

The main structures that pass through the carotid canal are:

– Internal carotid artery – Ascends through the carotid canal after entering the skull base. A key artery supplying blood to the brain.

– Carotid plexus – Sympathetic nerve fibers entwined around the internal carotid artery.

– Caroticotympanic nerves – Small branches from the carotid plexus supplying the middle ear.

– Deep petrosal nerve – A small branch from the carotid plexus carrying postganglionic sympathetic fibers. Joins the greater petrosal nerve to form the nerve of the pterygoid canal.

Q.Structures passing through foramen magnum?

The contents that pass through the foramen magnum are:

– Medulla oblongata

– Meninges

– Vertebral arteries

– Anterior spinal artery

– Posterior spinal arteries

– Spinal root of accessory nerve (CN XI)

– Dura mater

– Alar ligaments

– Apical ligament of the dens

– Tectorial membrane

– Spinal fluid

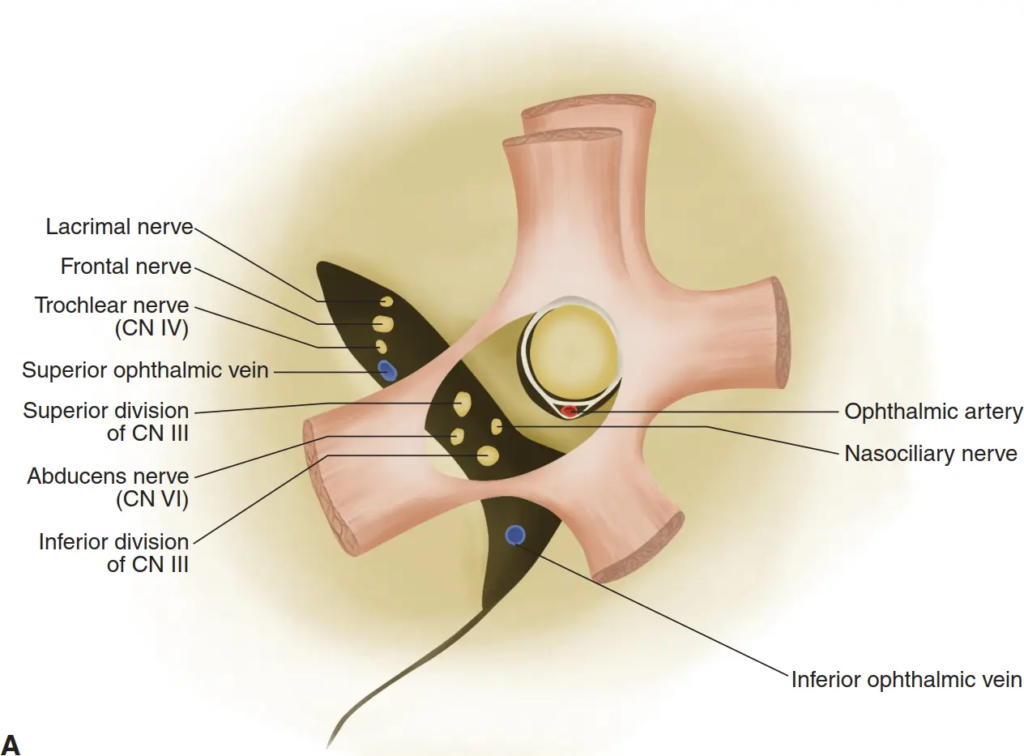

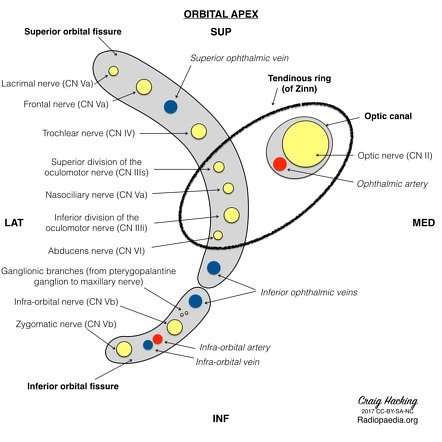

The superior orbital fissure is a major foramen located between the greater and lesser wings of the sphenoid bone. It serves as a passageway between the middle cranial fossa and the orbit.

The important contents that pass through the superior orbital fissure are:

– Lacrimal nerve (branch of ophthalmic division of trigeminal nerve)

– Frontal nerve (branch of ophthalmic division of trigeminal nerve)

– Trochlear nerve (CN IV) – Exits fossa here to enter the orbit

– Superior and inferior divisions of oculomotor nerve (CN III)

– Abducent nerve (CN VI) – Enters fossa here from the orbit

– Ophthalmic vein

– Orbital branches of middle meningeal artery

Additional structures found within the fissure itself:

– Annulus of Zinn – Tendinous ring that surrounds the optic foramen and ophthalmic structures.

Here is a list of the structures that pass through the jugular foramen:

– Glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX)

– Vagus nerve (CN X)

– Accessory nerve (CN XI)

– Inferior petrosal sinus

– Sigmoid sinus

– Meningeal branches of occipital and ascending pharyngeal arteries

– Arnold’s nerve (auricular branch of vagus nerve)

The jugular foramen is a large foramen located between the temporal and occipital bones in the skull base.

Q. Structures passing through foramen lacerum?

The foramen lacerum is an irregular opening located at the base of the skull, inferior to the apex of the petrous temporal bone.

The important contents that pass through or relate to the foramen lacerum are:

– Vidian nerve – Passes through the upper part of the foramen lacerum. It is formed from the union of the greater petrosal nerve and deep petrosal nerve.

– Cartilaginous part of the auditory tube – The pharyngotympanic tube passes just inferior and parallel to the foramen lacerum.

– Internal carotid artery – The lacerum segment of the internal carotid artery courses inferomedial to the foramen lacerum.

– Middle meningeal artery – A branch of the maxillary artery that passes inferior to the foramen lacerum.

– Ascending pharyngeal artery – Passes through the lower part of the foramen lacerum.

– Sympathetic plexus – Carotid plexus sympathetic nerves surround the internal carotid artery near the foramen lacerum.

Q.structures passing through foramen rotundum?

The foramen rotundum is a circular opening located in the sphenoid bone of the middle cranial fossa, just inferior to the apex of the petrous portion of the temporal bone. It allows passage of the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve and associated blood vessels between the middle cranial fossa and the pterygopalatine fossa.

structures that pass through the foramen rotundum:

– Maxillary nerve (V2 division of trigeminal nerve)

– Branches from the internal carotid artery, including the nerve of the pterygoid canal

– Inferior orbital veins

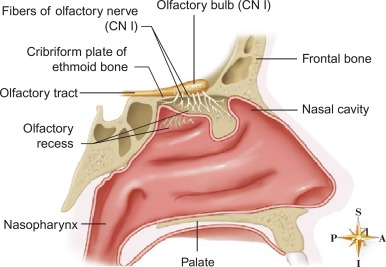

Q. What is cribriform plate and what structures pass through it ?

The cribriform plate is a thin, perforated part of the ethmoid bone that forms the roof of the nasal cavity and a portion of the anterior cranial fossa floor.

The main structures that pass through the holes (foramina) of the cribriform plate are:

– Olfactory nerve fibers (cranial nerve I) – These sensory nerve fibers pass from the olfactory epithelium in the nasal cavity through the cribriform plate foramina to reach the olfactory bulbs on the brain.

– Filaments of the anterior ethmoidal nerve – Branches of this nerve, which provides sensation to the nasal cavity, traverse the cribriform plate.

– Branches of the nasociliary nerve – Sensory and autonomic fibers going to and from the nasal mucosa pass through the cribriform plate.

– Blood vessels – Branches of the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries and veins go through the cribriform plate to supply the nasal cavity.

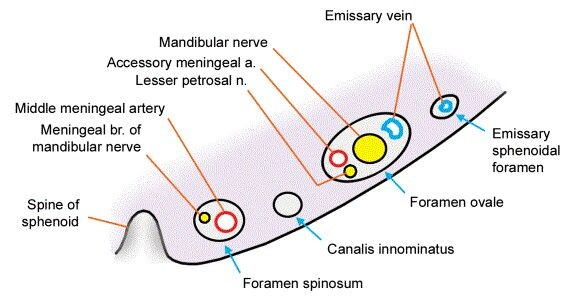

Q. Structures passing through foramen ovale?

The foramen ovale is located on the greater wing of the sphenoid bone and connects the middle cranial fossa to the infratemporal fossa. Knowing the structures passing through it is important for understanding cranial nerve pathways.

The main structures that pass through the foramen ovale are:

– Mandibular nerve (V3) – This is the third division of the trigeminal nerve (CN V) that provides sensory innervation to the lower face.

– Lesser petrosal nerve – This carries postganglionic parasympathetic fibers from the facial nerve to the otic ganglion.

– Accessory meningeal artery – A branch of the middle meningeal artery that supplies the dura mater.

– Emissary vein – Connects the cavernous sinus to the pterygoid plexus of veins.

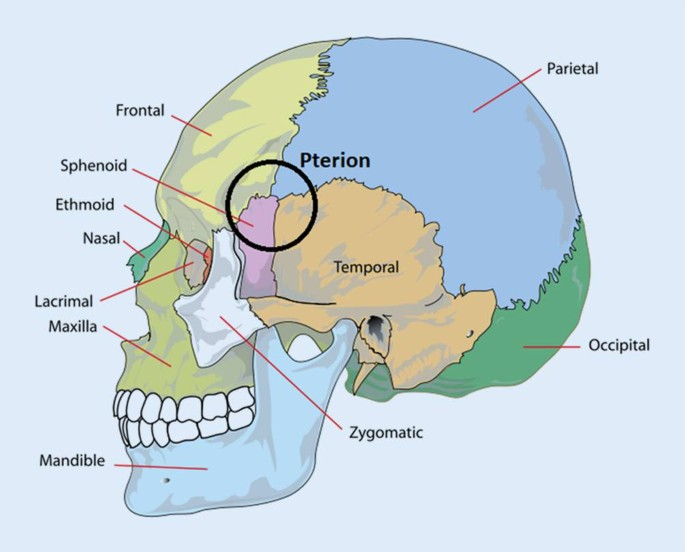

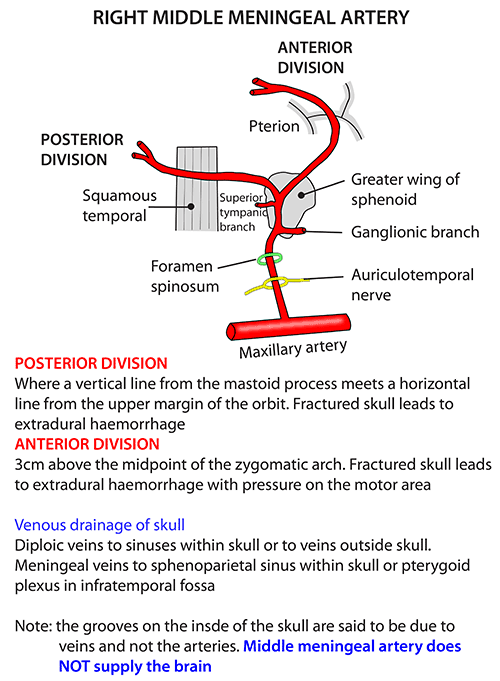

The pterion is an important H-shaped sutural junction in the skull located between the following four bones:

– Frontal

– Parietal

– Temporal

– Sphenoid

The importance of the pterion includes:

– It overlies the anterior branch of the middle meningeal artery. This is why the pterion is a common site for epidural hematomas from head trauma.

– It marks the anterior division of the middle meningeal artery from the main trunk.

– It provides a surgical access point to the anterior and middle cranial fossae as it overlies the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone.

– It allows for palpation of the anterior branch of the middle meningeal artery in some patients.

– It overlies the insula and Broca’s area in the brain, which are important language regions.

some common lytic (bone destroying) lesions that can affect the skull:

– Multiple myeloma – Cancer of plasma cells that causes lytic lesions throughout the skeleton, including the skull. This can lead to “punched-out” lesions on X-ray.

– Metastatic cancers – Cancers like breast, lung, thyroid, kidney and prostate cancer can metastasize to the skull and cause osteolytic lesions.

– Langerhans cell histiocytosis – Disorder that can affect the skull, especially in children, leading to bone destruction.

– Fibrous dysplasia – Benign tumor that causes expansion and thinning of cranial bones. Shows lytic areas on imaging.

– Paget’s disease – Chronic disorder where excessive bone breakdown and regrowth weakens bones like the skull.

– Osteomyelitis – Infection of the bone that can lead to osteolysis if it involves the skull.

– Brown tumors – Lytic lesions seen in hyperparathyroidism from elevated calcium leaching out of bone.

– Hemangioma – Benign vascular tumor that can cause lytic-looking lesions of the skull.

Q. Structures passing through Optic canal?

The optic canal connects the middle cranial fossa to the orbit. The optic canal is a bony canal in the skull that transmits the optic nerve (CN II) and ophthalmic artery.

Specifically, the structures passing through the optic canal are:

– Optic nerve (CN II) – The second cranial nerve that transmits visual information from the retina to the brain.

– Ophthalmic artery – A branch of the internal carotid artery that provides the main blood supply to the eyes and parts of the orbit.

– Sympathetic nerve fibers – Travel along the optic nerve to provide sympathetic innervation to the eyes.

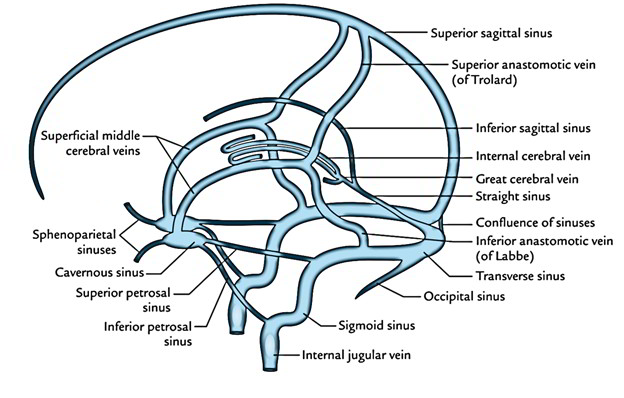

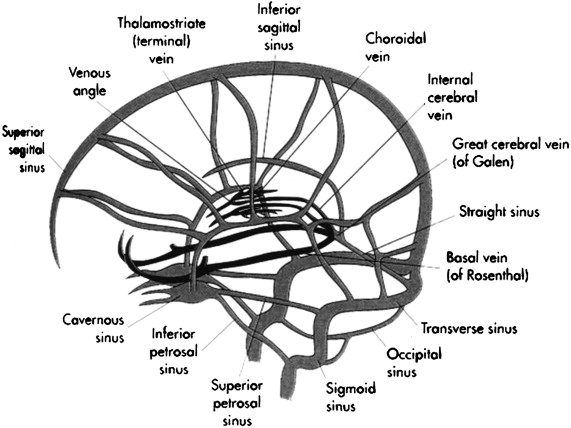

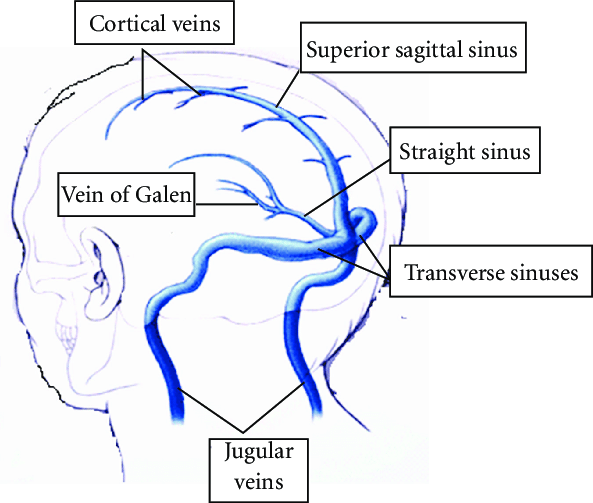

The venous sinuses of the skull can be categorized as:

Paired dural venous sinuses:

– Superior sagittal sinus – Runs along the attached margin of the falx cerebri.

– Inferior sagittal sinus – Runs along the free margin of the falx cerebri.

– Straight sinus – Formed by the union of the inferior sagittal and great cerebral vein.

– Transverse sinuses – Formed at the confluence of sinuses, become the sigmoid sinuses.

– Sigmoid sinuses – Continuation of transverse sinuses, exit the skull as internal jugular veins.

– Cavernous sinuses – On either side of the sella turcica, contain cranial nerves.

– Sphenoparietal sinuses – Paired sinuses connecting the cavernous sinus to superficial middle cerebral veins.

Unpaired dural venous sinuses:

– Occipital sinus – At the internal occipital protuberance between the converging transverse sinuses.

– Confluence of the sinuses – Where the superior sagittal, straight, and occipital sinuses meet.

The sinuses of the skull can be classified based on the cranial fossa they are associated with:

Anterior Cranial Fossa:

– Frontal sinus

– Anterior ethmoidal air cells

Middle Cranial Fossa:

– Sphenoid sinus

– Posterior ethmoidal air cells

Posterior Cranial Fossa:

– Occipital sinus

Infratemporal Fossa:

– Maxillary sinus

Multiple Fossae:

– Middle ethmoidal air cells (anterior and middle fossa)

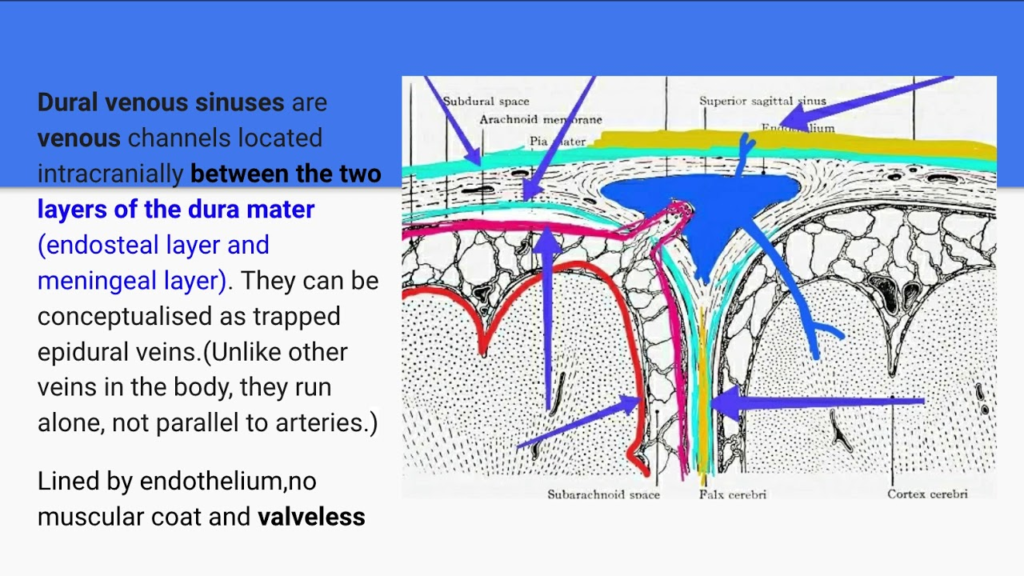

The venous sinuses of the brain are valveless structures. This has important clinical significance:

– Allows bidirectional blood flow in the sinuses. Blood can flow either towards or away from the heart.

– Predisposes to spread of infection. Lack of valves allows easy spread of pathogens through interconnected sinus network.

– Permits spread of thrombus. Clots can propagate bidirectionally through valveless sinuses. Risk of venous sinus thrombosis.

– No protection against backflow and pressure. Sinuses lack valves to prevent venous backflow or rising pressure. Risk of intracranial hypertension.

– Facilitates sampling of cerebral venous blood. Valveless nature enables easy catheterization and sampling of cerebral venous blood for diagnosis.

– Contributes to surgical risks. Surgery around valveless sinuses has risk of air embolism and uncontrolled bleeding due to lack of valves.

– Superior sagittal sinus – Receives most venous drainage from the brain and delivers it to the internal jugular vein.

– Cavernous sinuses – Allow passage of internal carotid arteries and cranial nerves III, IV, V1, V2, and VI. Connects venous systems of the brain and face.

– Transverse sinuses – Act as pathways for venous blood from the brain to return to the heart. Joins the sigmoid sinuses.

– Sigmoid sinuses – Receive blood from transverse and petrosal sinuses and become the internal jugular veins.

– Confluence of sinuses – Critical meeting point of major sinus drainage from the brain.

– Sphenoparietal sinuses – Provide an alternate drainage pathway between cavernous sinus and superficial cerebral veins.

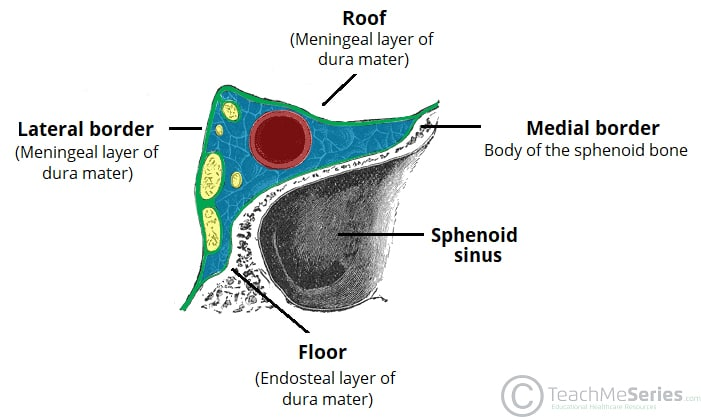

Here are some key anatomical details about the cavernous sinus and important structures within it:

– Paired structure – There is a cavernous sinus on each side of the sella turcica.

– Trabeculated appearance – Internally the cavernous sinus has a lattice-like trabecular structure.

– Lateral wall – Formed by the trigeminal nerve (CN V1, CN V2) and orbit.

– Medial wall – Formed by the pituitary gland, sphenoid bone, and internal carotid artery.

– Anterior – Connects to the orbital fissure and ophthalmic veins.

– Posterior – Joins the petrosal sinuses to form transverse sinus.

– Contains – Cranial nerves III, IV, V1, V2, VI, and the internal carotid artery.

– Receives – Ophthalmic veins, sphenoparietal sinus, superficial middle cerebral vein.

– Drains into – Transverse sinus and internal jugular vein.

– Vital structures – Internal carotid artery, oculomotor (CN III), trochlear (CN IV), trigeminal (CN V), abducens (CN VI) nerves.

– Clinical impact – Cavernous sinus thrombosis can affect all structures within it.

The hypoglossal canal is located in the occipital bone of the skull base. The following structures pass through the hypoglossal canal:

– Hypoglossal Nerve (CN XII) – This is the only structure that passes through the hypoglossal canal. It innervates the muscles of the tongue.

– Meningeal branch of the ascending pharyngeal artery – Travels through the hypoglossal canal to supply the meninges.

– Emissary vein – Connects the vertebral venous plexus to the internal jugular vein. Helps drain blood from the brain.

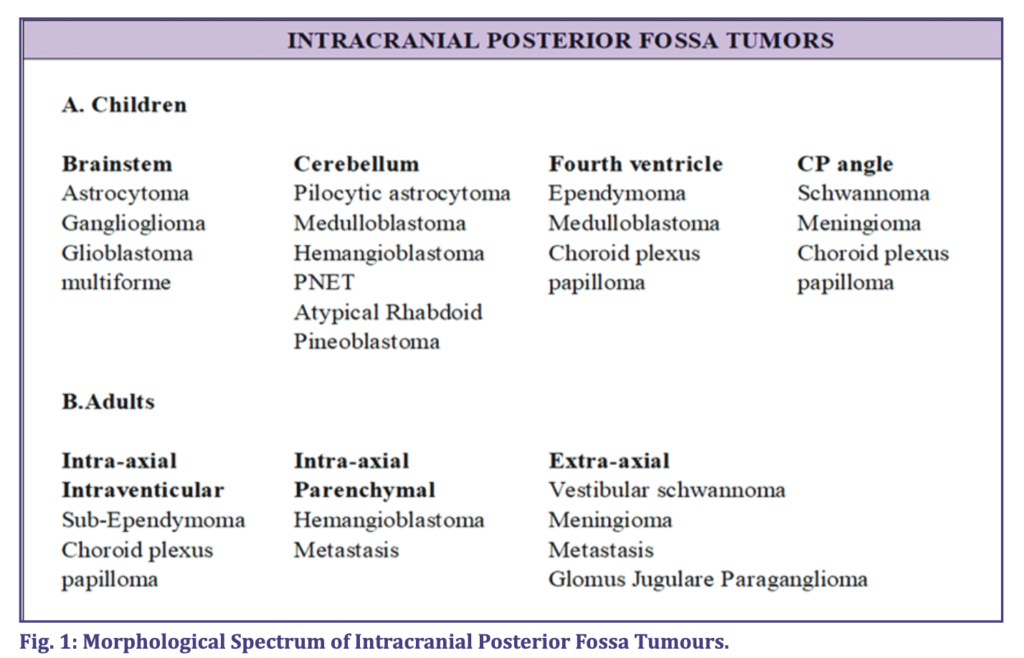

common tumors found in the different cranial fossae:

Anterior Cranial Fossa:

– Meningioma

– Pituitary adenoma

– Craniopharyngioma

– Optic nerve glioma

– Olfactory groove meningioma

Middle Cranial Fossa:

– Acoustic neuroma (vestibular schwannoma)

– Meningioma

– Pituitary adenoma (extending from sella turcica)

– Chordoma

– Chondrosarcoma

Posterior Cranial Fossa:

– Meningioma

– Schwannoma

– Ependymoma

– Medulloblastoma

– Hemangioblastoma

– Vestibular schwannoma (extending from internal auditory canal)

The clivus is an important bony structure located at the skull base in the posterior cranial fossa. Some key points about the clivus:

– Definition: It refers to the central part of the occipital bone that forms the floor of the posterior cranial fossa.

– Location: It is situated behind the dorsum sellae and basilar part of the occipital bone.

– Anatomical boundaries: Formed by the fusion of the basiocciput and basisphenoid bones. Extends from dorsum sellae to foramen magnum.

– Structures related: Borders the sella turcica, pituitary gland, pons, medulla oblongata, and vertebral artery.

– Clinical importance:

1) Tumors like chordoma, chondrosarcoma can arise from the clivus.

2) Fractures of the clivus can cause cranial nerve deficits and CSF leaks.

3) Assessment of clivus blumenbachii angle is used to evaluate platybasia.

Anatomically, the clivus refers to the central portion of the occipital bone that forms the floor of the posterior cranial fossa. It has the following key features:

– Formed by the fusion of two bones – the basiocciput and basisphenoid bones.

– Extends from the dorsum sellae of the sphenoid bone to the foramen magnum.

– Situated posterior to the sella turcica and pituitary fossa.

– Borders the brainstem structures – the pons anteriorly and the medulla oblongata inferiorly.

– The abducens nerves (CN VI) pass laterally in the clivus dural folds along its length.

– The basilar plexus lies inferiorly between the clivus and the pharyngeal tubercle.

– The longus capitis and rectus capitis anterior muscles attach to the clivus.

– The vertebral artery runs in a canal situated near the clivus.

Specifically:

– The clivus is formed by the fusion of two bony parts – the basiocciput and basisphenoid bones.

– Where these two bones meet is a remnant of hyaline cartilage called the spheno-occipital synchondrosis.

– This hyaline cartilage allows growth of the clivus during childhood and ossifies into bone in the late teens/early 20s.

– Premature fusion of the synchondrosis can result in clival abnormalities and impaired skull base growth.

– After ossification, the boundary between the two parts of the clivus is still visible as a faint line on radiographs called the spheno-occipital synchrondrosis.

There are several fontanelles (soft spots) in an infant’s skull that eventually fuse over time:

– Anterior fontanelle – Located on the anterior skull at the junction of the frontal and parietal bones. Closes between 12-18 months.

– Posterior fontanelle – Located on the posterior skull at the junction of the parietal and occipital bones. Closes between 2-3 months.

– Sphenoidal fontanelle – Located at the junction of the sphenoid and frontal bones. Closes within a few months after birth.

– Mastoid fontanelle – Located at the junction of the occipital, temporal and parietal bones. Closes within a few months after birth.

– Anterior median fontanelle – Located in the midline between the frontal bones. Closes around 8-12 months.

– Posterior median fontanelle – Located in the midline between the occipital bones. Closes within a few months after birth.

The anterior fontanelle is the largest and most important for clinical assessment. Premature closure of fontanelles or delayed closure beyond expected timelines can indicate developmental issues.

Q. venous sinuses in different fossa of skull?

– Middle cranial fossa: Contains the cavernous sinuses. These sinuses surround the internal carotid arteries and contain the oculomotor, trochlear, trigeminal (V1, V2) and abducens nerves.

– Posterior cranial fossa:

– Transverse sinuses – Formed by the convergence of the superior sagittal and straight sinuses, drain blood from the posterior portion of the brain.

– Sigmoid sinuses – Continuation of the transverse sinuses, curve inferiorly on each side to become the internal jugular veins.

– Anterior cranial fossa:

– Superior sagittal sinus – Runs lengthwise along the interior surface of the skull, along the attached edge of the falx cerebri. Drains the medial surfaces of the cerebral hemispheres.

– Inferior sagittal sinus – Much smaller, runs along the inferior edge of the falx cerebri. Joins the great cerebral vein to form the straight sinus.

– Sella turcica/Hypophyseal fossa:

– Cavernous sinuses receive intercavernous sinuses (transverse between the two cavernous sinuses) and inferior & superior petrosal sinuses that drain the basilar plexus.

Q.Importance of clivus?

Here are some key points about the importance of the clivus:

– Anatomy: The clivus is a bony part of the skull base, forming the sloped surface at the anterior portion of the posterior cranial fossa. It is formed by the fusion of the basiocciput and basisphenoid bones.

– Structures related to clivus:

– Brainstem and cranial nerves IX-XII pass through the foramen magnum located inferior to the clivus.

– Basilar artery runs along the clivus.

– Dorsum sellae is located superior to the clivus.

– Clinical significance:

– Fractures of the clivus can cause damage to cranial nerves and vascular structures that traverse this area. This can lead to cranial nerve palsies, stroke, or carotid-cavernous fistulas.

– Chordomas are rare tumors that can arise from embryonic remnants of the notochord within the clivus. They can extend into the nasopharynx.

– Clival lesions or platybasia (flattening of the clivus) can cause basilar invagination, leading to compression of the brainstem, cranial nerves, or cerebellum.

– Understanding the anatomy of the clivus allows for surgical access to the brainstem and skull base. Approaches like the transoral approach utilize the anatomical position of the clivus.

Inside the skull, the facial nerve exits the brainstem from the pons as two rootlets that wrap around the abducens nucleus to form the nerve trunk inside the cerebellopontine angle cistern.

Origin – The facial nerve originates from the pons region of the brainstem, with two rootlets (nervus intermedius and motor root) emerging and wrapping around the abducens nucleus.

Intracranial course:

– Enters internal auditory canal (IAC) of temporal bone along with vestibulocochlear nerve

– Forms geniculate ganglion inside IAC – contains cell bodies of taste and secretomotor fibers

– Gives off greater petrosal, nerve to stapedius, and chorda tympani branches

– Exits skull via stylomastoid foramen

Extratemporal course:

– Travels through parotid gland and gives off five major facial branches:

1. Temporal – forehead and scalp

2. Zygomatic – cheek

3. Buccal – cheek

4. Marginal mandibular – lower lip

5. Cervical – neck

The intracranial segments of the facial nerve branches are:

– Greater petrosal nerve – Exits from the geniculate ganglion, carries parasympathetic fibers to the pterygopalatine ganglion via the pterygoid canal.

– Nerve to stapedius – Exits the facial nerve trunk and innervates the stapedius muscle in the middle ear.

– Chorda tympani – Originates from the vertical segment of the facial nerve, carries taste from the anterior 2/3 of the tongue and parasympathetic innervation to the submandibular gland. Exits skull through the petrotympanic fissure.

The main facial nerve trunk continues its course inside the facial canal of the temporal bone. It gives off no further branches while inside the skull.

The extratemporal course involves emerging from the stylomastoid foramen to give rise branches for facial expression – temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular, and cervical.

So in summary, the key intracranial branches of the facial nerve are the greater petrosal, nerve to stapedius, and chorda tympani branching

Q.Cranial nerve in relation to clivus?

Here is a brief overview of the cranial nerves that relate to the clivus:

– Abducens Nerve (CN VI) – Runs along the clivus after emerging from the pons. It passes through Dorello’s canal in the clivus, bounded by the petroclinoid ligament.

– Facial Nerve (CN VII) – The facial nerve enters the internal auditory canal posterior to the clivus. The greater petrosal nerve, a branch of CN VII, grooves the clivus as it courses to the pterygopalatine ganglion.

– Glossopharyngeal (CN IX), Vagus (CN X), Accessory (CN XI) nerves – These nerves exit the jugular foramen, which is situated midway between the lateral end of the clivus and the styloid process.

– Hypoglossal Nerve (CN XII) – This nerve passes forward in the hypoglossal canal, located superior to the occipital condyle under the posterior end of the clivus.

The spheno-occipital synchondrosis is an important growth center in the skull that typically fuses between the ages of 13-19 years. Here are some key points about the ossification timeline of this structure:

– Fusion begins around 11-13 years in girls and 13-15 years in boys.

– Complete fusion usually occurs between 15-19 years in girls and 17-21 years in boys.

– Girls tend to fuse earlier than boys due to earlier onset of puberty.

– Premature complete fusion before age 11 is abnormal and can result in restricted skull growth.

– Delayed fusion beyond 21 years can be normal, but may also indicate growth hormone deficiency or other endocrine disorders if other growth plates have fused.

– The spheno-occipital synchondrosis is one of the last skull sutures to ossify. Only the medial clavicular epiphysis fuses later, at around age 25.

Q. What is Crysta Galli?

Crista galli is a small protrusion of bone located at the midline of the inner surface of the ethmoid bone. The crista galli is a thick, midline, smooth triangular process arising from the superior surface of the ethmoid bone, projecting into the anterior cranial fossa

Here are some key features of the crista galli:

– It projects upward into the anterior cranial fossa, just posterior to the frontal bone.

– The falx cerebri, a fold of dura mater, attaches to the crest of the crista galli.

– It serves as an important anchor point for the falx cerebri as it separates the left and right cerebral hemispheres.

– The perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone and cribriform plates form the lateral boundaries of the crista galli.

– It has a tuberous frontal end and a small vertical spine projecting posteriorly.

– There is a foramen on each side of the spine for olfactory nerves to pass through the cribriform plates.

– The crista galli provides an attachment point for the meningeal layers and nasal septal cartilage.

– It is more prominent and palpable in children, becoming smoother with age as the brain expands.

– The function is to provide structural support and anchor the dura mater and nasal septum at the midline.

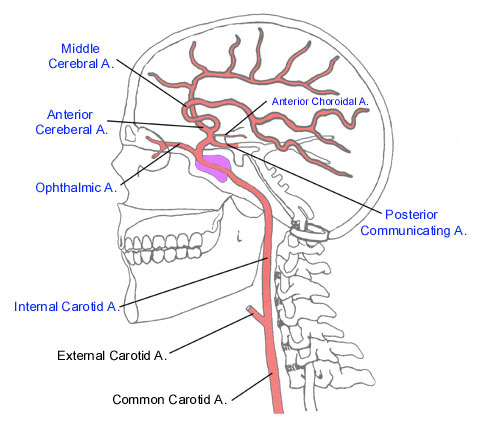

Q. Blood supply of brain?

– The brain receives blood supply from two paired internal carotid arteries and two vertebral arteries which join to form the cerebral arterial circle (of Willis) at the base of the brain.

Internal Carotid Artery:

– Enters the cranial cavity and gives off several branches:

1. Ophthalmic artery – supplies the eye and orbit

2. Anterior cerebral artery – supplies the frontal lobe

3. Middle cerebral artery – supplies the lateral surface of brain (temporal, parietal, occipital lobes)

4. Posterior communicating artery – connects with posterior circulation

Vertebral Arteries:

– Travel through foramina in cervical vertebrae and join intracranially to form the basilar artery.

– Branches of basilar artery supply brainstem, cerebellum, inner ear, posterior-inferior parts of brain.

– Branches include pontine arteries, anterior inferior cerebellar artery, posterior cerebral artery.

Posterior Cerebral Artery:

– Supplies the occipital lobe and inferior surface of temporal and parietal lobes.

– Connects with internal carotid circulation via posterior communicating artery.

Anterior vs Posterior Circulation:

– Anterior circulation is from internal carotids.

– Posterior circulation is from vertebral arteries/basilar artery.

– Communicating arteries connect the two systems.

Internal Carotid Artery:

– Ipsilateral eye/forehead weakness

– Contralateral body weakness and sensory loss

– Aphasia if dominant side affected

Anterior Cerebral Artery:

– Contralateral leg weakness

– Urinary incontinence

– Apathy, depression, personality changes

Middle Cerebral Artery:

– Contralateral face, arm and leg weakness

– Contralateral sensory loss

– Aphasia if dominant hemisphere affected

Posterior Cerebral Artery:

– Contralateral vision cuts

– Contralateral sensory loss in limbs

– Memory deficits

Vertebral Artery:

– Ipsilateral cranial nerve palsies (IX, X, XI)

– Ipsilateral ataxia, vertigo, nystagmus

– Contralateral sensory loss

Basilar Artery:

– Bilateral motor weakness

– Bilateral cranial nerve palsies

– Aphasia if pontine stroke

Cerebellar Arteries:

– Ipsilateral ataxia, dysmetria

– Ipsilateral vertigo, vomiting

– Incoordination on same side as lesion

The intercavernous sinuses are venous structures located between the right and left cavernous sinuses at the base of the brain.

Formation:

– The intercavernous sinuses are formed from the two cavernous sinuses coming together.

– The cavernous sinuses are large, irregular venous channels on either side of the sella turcica. They receive blood from the ophthalmic veins as well as the superficial middle cerebral veins.

– As the right and left cavernous sinuses come together anteriorly and posteriorly, they form the anterior and posterior intercavernous sinuses.

Drainage:

– The intercavernous sinuses drain blood from the cavernous sinuses into the inferior petrosal sinuses.

– Specifically, the anterior intercavernous sinus drains into the inferior petrosal sinuses bilaterally.

– The posterior intercavernous sinus drains into the inferior petrosal sinuses more unilaterally on each side.

– From the inferior petrosal sinuses, blood then drains into the internal jugular veins.

So in summary:

– The intercavernous sinuses form from the union of the right and left cavernous sinuses.

– They provide a channel for venous blood drainage from the cavernous sinuses into the inferior petrosal sinuses and internal jugular veins.

Q.different venouses sinuses of brain , their formation and drainage?

different venous sinuses of the brain, their formation, and drainage:

The venous sinuses are endothelial-lined channels located between the two layers of dura mater that surround the brain. They collect blood from the brain and eventually drain into the internal jugular veins.

The major venous sinuses include:

– Superior sagittal sinus – Located in the attached margin of the falx cerebri. Formed by the convergence of superficial cerebral veins. Drains into the right transverse sinus.

– Inferior sagittal sinus – Formed along the free margin of the falx cerebri. Drains into the straight sinus.

– Straight sinus – Formed at the junction of the falx cerebri and tentorium cerebelli. Drainage from the inferior sagittal and great cerebral vein. Drains into the left transverse sinus.

– Transverse sinuses – Formed at the posterior attached margins of the tentorium cerebelli. The right is usually dominant. Drain into the sigmoid sinuses.

– Sigmoid sinuses – Formed at the lateral margins of the posterior fossa. Curve anteriorly on each side to become the internal jugular veins.

– Occipital sinus – Located along the attached margin of the falx cerebelli. Drains into the confluence of sinuses.

– Cavernous sinuses – Located on either side of the sella turcica. Receive blood from the ophthalmic veins and drain via the petrosal sinuses into the internal jugular vein.

In summary, the cerebral veins join to form large sinuses between layers of dura mater. These venous channels ultimately collect blood from the brain and drain into the internal jugular veins that return blood to the heart. The pattern of convergence optimizes venous drainage of the brain.

Q. Vein of Galen?

– The vein of Galen is a large, short median vein formed by the union of the two internal cerebral veins and the basal veins.

– It receives blood from the deep structures of the brain and is an important landmark in the brain.

– The vein of Galen drains into the straight sinus, which is part of the venous sinuses of the dura mater that drain blood from the brain.

– It provides a pathway for blood return from deep cerebral structures back to the heart via the internal jugular veins.

– Abnormalities in the development of the vein of Galen, such as aneurysmal malformations, can lead to various complications like hydrocephalus, cardiac failure in infants.

– Thrombosis of the vein of Galen can result in hemorrhagic infarction of the deep brain structures it drains.

– The vein of Galen plays a vital role in the venous drainage of the brain along with the other dural sinuses and cerebrovenous systems.

– Imaging of the vein of Galen provides important anatomical information and indications of abnormalities in the deep venous drainage system.

– Overall, the vein of Galen is a clinically important cerebral vein that serves as a major drainage pathway for deep brain structures and can be associated with certain vascular malformations and thrombosis complications if malformed or obstructed.

Q. Blood supply brain?

The brain has a highly organized arterial blood supply that delivers oxygen and nutrients. The two main arteries are the internal carotid arteries and the vertebral arteries.

Internal Carotid Arteries

– Arise from the common carotid arteries on each side of the neck.

– Enter the cranial cavity through the carotid canals in the temporal bone.

– Each internal carotid artery divides into the anterior cerebral artery and the middle cerebral artery.

– Thrombosis causes ischemia in the anterior and middle cerebral artery territories.

– Symptoms include contralateral weakness and sensory loss, aphasia if dominant hemisphere is affected.

– Patient may experience hemiparesis, hemisensory deficit, hemianopia, neglect, and gaze deviations.

Anterior Cerebral Arteries (ACA)

– Supplies the medial surfaces of the cerebral hemispheres.

– Connected to the anterior communicating artery which joins the two ACAs.

– Branches include the anterior frontal arteries, anterior parietal arteries, and medial striate arteries.

– Thrombosis affects medial frontal and parietal regions.

– Symptoms include contralateral leg weakness, urinary incontinence, personality changes, and reduced spontaneous movement.

Middle Cerebral Arteries (MCA)

– Largest branch of the internal carotid arteries.

– Supplies the lateral surfaces of the cerebrum.

– Branches include lateral striate arteries, anterior temporal arteries, and posterior temporal arteries.

– Most common site of stroke. Thrombosis causes large lateral infarcts.

– Symptoms include contralateral hemiparesis, hemisensory loss, hemianopia, aphasia.

Vertebral Arteries

– Arise from the subclavian arteries.

– Ascend through the transverse foramen in each cervical vertebra.

– Enter the cranium through the foramen magnum and join to form the basilar artery.

– Thrombosis can affect the brainstem, cerebellum, and inner ear.

– Symptoms include vertigo, nausea, nystagmus, ipsilateral ataxia, and contralateral weakness.

Basilar Artery

– Formed by the union of the two vertebral arteries.

– Runs along the pons and bifurcates into the two posterior cerebral arteries.

– Branches supply the brainstem, cerebellum, and inner ear.

– Thrombosis causes bilateral ischemia of the brainstem, cerebellum and occipital lobes.

– Symptoms include vertigo, diplopia, bilateral weakness, sensory loss, locked-in syndrome.

Posterior Cerebral Arteries (PCA)

– Formed from the bifurcation of the basilar artery.

– Supplies the occipital lobes, brainstem, and thalamus.

– Connected by the posterior communicating arteries to the internal carotid system.

– Thrombosis causes infarction in the thalamus and occipital lobe.

– Symptoms include contralateral sensory loss, homonymous hemianopia, visual hallucinations.

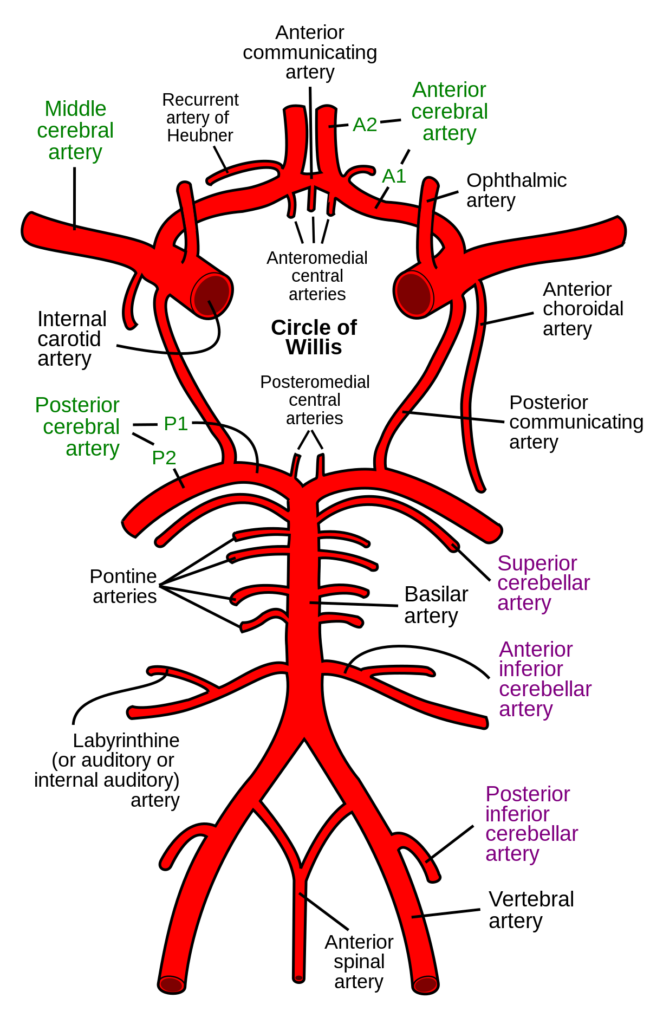

– The circle of Willis is an arterial polygon (circular anastomosis) located at the base of the brain that distributes blood to the brain and surrounding structures.

– It is formed by the two internal carotid arteries and the two vertebral arteries anastomosing with each other and the anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries.

– The key components are:

– Internal carotid arteries (anterior circulation)

– Anterior cerebral arteries

– Anterior communicating artery

– Middle cerebral arteries

– Posterior cerebral arteries (posterior circulation)

– Vertebral arteries

– Basilar artery

– Posterior communicating arteries

– The circle of Willis creates collateral circulation and allows blood flow to be maintained if there is a blockage in one of the arteries.

– It functions as an equalizer of blood pressure between the anterior and posterior portions of the brain and between the two sides of the brain.

– An incomplete circle of Willis is a risk factor for stroke and vascular dementia due to the lack of collaterals.

Q.what are diploic veins and their significance?

The diploic veins are small valveless veins that drain the diploë space in the skull bones. Here are some key points about their anatomy and significance:

– They are located between the inner and outer tables of the cranial bones, in the diploë space.

– The diploë space is filled with spongy bone and bone marrow.

– Diploic veins form an anastomotic network that drains blood from this space.

– They drain into the various venous sinuses of the dura mater, mainly the epidural venous sinuses.

– The frontal, anterior temporal, and posterior diploic veins drain into the supraorbital, sphenoparietal, and transverse sinuses respectively.

– They communicate with the deep veins of the brain through small emissary veins that pass through skull foramina.

– Diploic veins act as an alternate drainage pathway for intracranial venous blood flow.

– They become enlarged and engorged in cases of increased intracranial pressure and venous obstruction.

– On CT/MRI, enlarged diploic veins appear as linear hypersensities in the diploë space and are an indication of increased intracranial pressure.

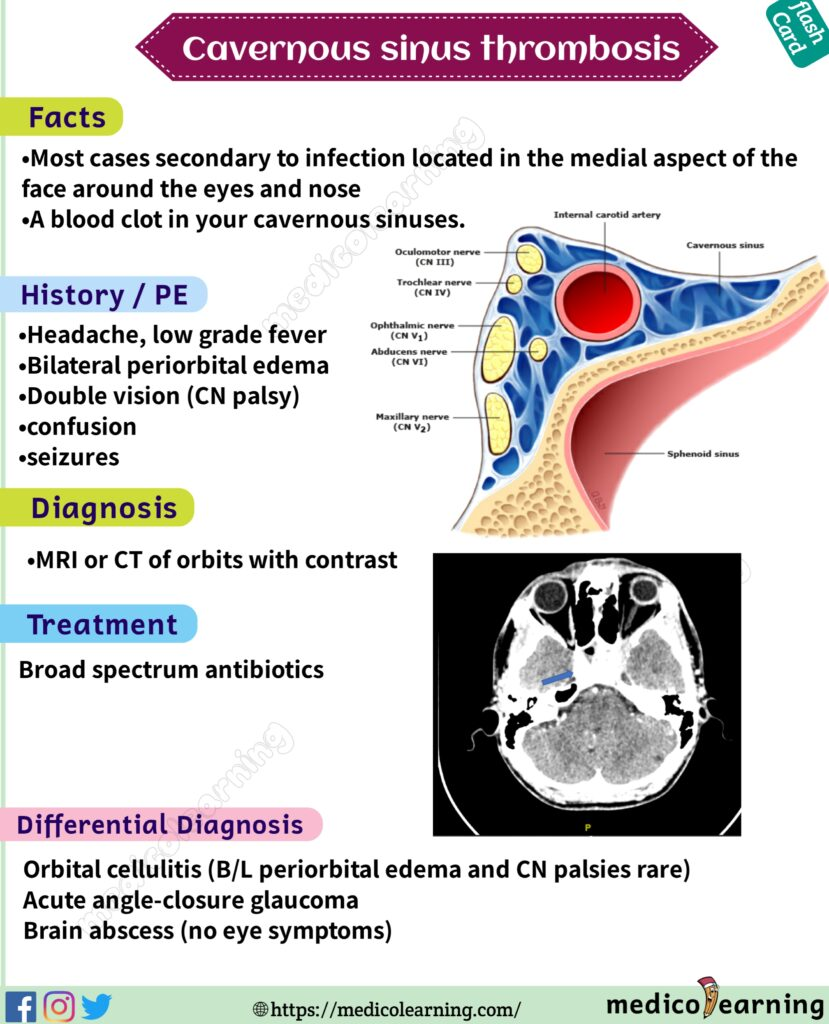

Q.Cavernous sinus structure?

The cavernous sinus is a crucial venous structure located on either side of the sella turcica in the base of the skull. Here are some key points about the cavernous sinus anatomy:

– It is located lateral to the sella turcica and pituitary gland, behind the eye orbits.

– It contains the internal carotid artery and 6th cranial nerve(abducent nerve) as these structures course through the skull.

– It receives blood from the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins, sphenoparietal sinus, and superficial middle cerebral vein.

– It drains posteriorly into the petrosal sinus and then into the internal jugular vein.

– It communicates with the contralateral cavernous sinus via intercavernous sinuses.

– The sinus walls contain filaments of cranial nerves III, IV, V1 and V2, which control eye movement and sensation.

– Important relations include the pituitary gland medial to it, Meckel’s cave with trigeminal nerve laterally, and occulomotor, trochlear, abducens and ophthalmic nerves passing through the sinus.

– It lacks a complete endothelial lining, making it susceptible to spread of infection.

– Cavernous sinus thrombosis is a serious condition where the sinus fills with infected clot.

– Cavernous sinuses are located on either side of the sella turcica and contain the internal carotid artery and cranial nerves III, IV, V1, V2, and VI.

– Cavernous sinus thrombosis involves formation of a blood clot within the cavernous sinus, obstructing venous drainage.

– Common causes are infections of the face, sinuses, ears, or teeth spreading to the cavernous sinus.

– Symptoms include headache, eye swelling and redness, drooping eyelid (ptosis), fixed or dilated pupil, double vision (diplopia), and impaired eye movements.

– Other features can include fever, decreased consciousness, and seizures.

– The infection can spread from the cavernous sinus to other structures, leading to meningitis, cerebral abscess, or brainstem infarction.

– On examination, findings include periorbital edema, proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, cranial nerve palsies (III, IV, V, VI), and chemosis.

– Imaging like CT or MRI shows fluid collection and enlargement of the cavernous sinus, with filling defects from clot formation.

– Prompt antibiotic treatment and sometimes surgical drainage of the sinuses is required to manage cavernous sinus thrombosis.

– Delay in treatment can result in permanent vision loss, stroke, or death due to sepsis.

Q.how csf is formed and circulated?

Formation:

– CSF is produced mainly by the choroid plexus in the ventricles of the brain.

– It is formed by filtration of blood plasma across choroid plexus epithelial cells.

– About 500 ml of CSF is produced per day in healthy adults.

Circulation:

– CSF flows from the lateral ventricles to the third ventricle via the interventricular foramen.

– From the third ventricle, CSF passes through the cerebral aqueduct into the fourth ventricle.

– It then enters the subarachnoid space around the brain and spinal cord via the median aperture and lateral apertures of the fourth ventricle.

– CSF is reabsorbed into venous blood via arachnoid granulations mainly located along the superior sagittal sinus.

– Some CSF is also absorbed via spinal nerve root sheaths and lymph vessels.

– CSF flows in a pulsatile, unidirectional manner around the central nervous system.

– Its circulation provides mechanical protection, chemical stability, and removal of waste products from the brain.

– CSF pressure is measured during a lumbar puncture, with the patient lying on their side.

– Normal CSF opening pressure in adults is 50-180 mm H2O or 70-200 mm CSF.

– In children, the normal range is slightly higher – 80-180 mm H2O.

– Intracranial pressure (ICP) is equivalent to CSF pressure in the absence of any obstruction.

– CSF pressure is kept relatively constant by production and absorption of CSF and normal blood pressure in the brain.

– Elevated ICP (>200 mm H2O) can indicate issues like brain tumors, infection, stroke or trauma.

– Low CSF pressure (<60 mm H2O) can occur due to CSF leakage, dehydration or connective tissue disorders.

– CSF pressure is regulated by hydrostatic and osmotic forces across choroid plexus and arachnoid granulations.

– Conditions disrupting CSF circulation like hydrocephalus can increase CSF pressure.

– CSF pressure is monitored to diagnose and manage intracranial hypertension in neurological conditions.

Cavernous sinus thrombosis can result in periorbital edema and diplopia due to the following mechanisms:

– The cavernous sinus located on each side of the sella turcica contains the ophthalmic veins that drain the eye sockets.

– Thrombosis or clot formation within the cavernous sinus blocks venous drainage from the eyes.

– This venous congestion and damming of blood causes fluid leakage and periorbital edema around the eyes.

– The cranial nerves III, IV, VI that control eye movement also pass through the cavernous sinus.

– The clot and inflammation affects the function of these nerves as they traverse the sinus.

– Specifically, cranial nerve VI palsy results in an impairment of lateral gaze.

– Cranial nerve III palsy leads to ptosis, pupil dilation and eye movement deficits.

– The multiple eye movement deficits lead to double vision or diplopia when the person attempts to look sideways.

– In severe cases, the periorbital edema can be severe enough to cause proptosis or bulging of the eye outward.

– Relief of the sinus obstruction by antibiotics or surgery is required to reduce the venous congestion, edema and cranial nerve inflammation causing these eye signs.

– Facial infections – Sinusitis, dental abscesses, eyelid infections, etc. that spread to the cavernous sinus located behind the orbits and sinuses. This is a common cause. 50%

– Trauma or surgery – Injuries and procedures near the cavernous sinus that introduce infection.

– Hematologic disorders – Conditions like polycythemia that increase blood viscosity and clotting risk.

– Pregnancy/childbirth – Increased risk of clots postpartum.

– Vascular anomalies – Abnormal communications between cavernous sinus and facial veins.

– Immune deficiency – HIV, chemotherapy, etc. that allow infections to spread.

– Inflammatory disorders – Lupus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

– Adjacent infections – Meningitis, osteomyelitis of skull base.

– Medications – Oral contraceptives and hormones that increase clotting.

– Malignancies – Cancers like leukemia that increase thrombosis risk.

– Genetic factors – Prothrombotic mutations.

Revision Cranial fossa?

Forms the floor of the cranial cavity

Separates the brain from other facial structures

3 OverviewFormed by ethmoid, sphenoid, occipital, paired frontal, and paired temporal bones.

4 OverviewSubdivided into 3 regions: the anterior, middle, and posterior cranial fossae.

5 Anterior Cranial Fossa

Most shallow and superior of the three cranial fossaeLies superiorly over the nasal and orbital cavitiesAccommodates the anteroinferior portions of the frontal lobes of the brain

6 Anterior Cranial Fossa: Borders

Anteriorly and laterally bounded by the inner surface of the frontal bonePosteriorly and medially bounded by the limbus of the sphenoid bonePosteriorly and laterally it is bounded by the lesser wings of the sphenoid boneThe floor consists of the frontal bone, ethmoid bone and the anterior aspects of the body and lesser wings of the sphenoid bone

7 Anterior Cranial Fossa : Contents

Frontal crest: acts as a site of attachment for the falx cerebri (a sheet of dura mater that divides the two cerebral hemispheres)Crista galli: midline of ethmoid bone, acts as another point of attachment for the falx cerebriCribriform plate: on either site of the crista galli, supports the olfactory bulb and has numerous foramina that transmit vessels and nerves.Anterior clinoid processes: rounded ends of the lesser wings, serve as a place of attachment for the tentorium cerebelli (a sheet of dura mater that divides the cerebrum from the cerebellum)

8 Anterior Cranial Fossa : Foramina

Cribriform plate: numerous small foramina, transmiting olfactory nerve fibers. 2 larger foramen;Anterior ethmoidal foramen transmits the anterior ethmoidal artery, nerve and veinPosterior ethmoidal foramen transmits the posterior ethmoidal artery, nerve and vein

9 Anterior Cranial Fossa : Clinical Relevance

Cribriform plate: thinnest part, most likely to fractureAnosmiaCSF rhinorrhoea: leakage of CSF into the nasal cavity

10 Middle Cranial FossaAs its name suggests, centrally in the cranial floorButterfly shapedAnteriorly and laterally: lesser wings of the sphenoid boneAnteriorly and medially: limbus of the sphenoid bonePosteriorly and laterally: superior border of the petrous part of the temporal bonePosteriorly and medially: dorsum sellae of the sphenoid boneFloor: the body and greater wing of the sphenoid, and the squamous and petrous parts of the temporal bone.

11 Middle Cranial Fossa: Central Part

Formed by the body of the sphenoid boneContains the sella turcica(turkish saddle), acts to hold and support the pituitary glandTuberculum sellae (horn of the saddle): anterior wall of the sella turcica, and the posterior aspect of the chiasmatic sulcusHypophysial fossa or pituitary fossa (seat of the saddle): a depression in the body of the sphenoid, which holds the pituitary glandDorsum sellae (back of the saddle): posterior wall of the sella turcica, separates the middle cranial fossa from the posterior cranial fossa.

12 Middle Cranial Fossa: Lateral Parts

Formed by the greater wings of the sphenoid bone, and the squamous and petrous parts of the temporal bonesSupport the temporal lobes of the brainThe site of many foramina

13 Foramina of the Sphenoid Bone

Optic canals: optic nerves (CN II) and ophthalmic arteries, connected by the chiasmatic sulcusSuperior orbital fissure: opens anteriorly into the orbit; contains the oculomotor nerve (CN III), trochlear nerve (CN IV), ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve (CN V1), abducens nerve (CN VI), opthalmic veins and sympathetic fibers Foramen rotundum: transmits the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve (CN V2).Foramen ovale: the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve (CN V3) and accessory meningeal arteryForamen spinosum: transmits the middle meningeal artery, middle meningeal vein and a meningeal branch of CN V3

14 Foramina of the Temporal Bone

Hiatus of the greater petrosal nerve: transmits the greater petrosal nerve (a branch of the facial nerve), and the petrosal branch of the middle meningeal arteryHiatus of the lesser petrosal nerve – transmits the lesser petrosal nerve (a branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve).Carotid canal – located posteriorly and medially to the foramen ovale. This is traversed by the internal carotid artery, the deep petrosal nerve also passes through this canalForamen lacerum: At the junction of the sphenoid, temporal and occipital bones, filled with cartilage

15 Clinical Relevance: Pituitary Surgery

The pituitary gland lies in the sella turcica of the sphenoid boneIn cases of a pituitary tumour, it may need to be removed surgically.usually by a endoscopic transsphenoidal approachThe sphenoid sinus is opened and the endoscope passes through to the pituitary glandComplications of pituitary surgery include CSF rhinorrhoea, meningitis, diabetes insipidis, haemorrhage and visual disturbances

16 Posterior Cranial Fossa

Most posterior and deep of the three cranial fossaeAccommodates the brainstem and cerebellumThree bones: the occipital bone and the two temporal bones.Anteriorly and medially: dorsum sellae of the sphenoid boneAnteriorly and laterally: superior border of the petrous part of the temporal bone.Posteriorly: internal surface of the squamous part of the occipital boneFloor: mastoid part of the temporal bone and the occipital bone

17 Posterior Cranial Fossa – Foramina

Internal acoustic meatus: transmits the facial nerve (CN VII), vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII) and labrynthine arteryForamen magnum: transmits the medulla of the brain, meninges, vertebral arteries, spinal accessory nerve (ascending), dural veins and anterior and posterior spinal arteriesJugular foramina: transmits the glossopharyngeal nerve, vagus nerve, spinal accessory nerve (descending), internal jugular vein, inferior petrosal sinus, sigmoid sinus and meningeal branches of the ascending pharyngeal and occipital arteries. Hypoglossal canal: Hypoglossal nerve

18 Clinical Relevance: Cerebellar Tonsillar Herniation

Downward displacement of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnumProduced by a raised intracranial pressure; causes include hydrocephalus, space occupying lesions, and a malformed posterior cranial fossaCerebellar tonsillar herniation results in the compression of the pons and medulla, which contain the cardiac and respiratory centers

Arnold-Chiari malformation involves the downward displacement of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum into the upper spinal canal. It has the following key imaging findings:

– On MRI, the cerebellar tonsils are positioned at least 5mm below the foramen magnum.

– The fourth ventricle appears elongated and tethered as it descends into the foramen magnum.

– There may be crowding at the craniovertebral junction and compression of the CSF pathways.

– Syrinxes or fluid-filled cavities may be seen in the spinal cord as a secondary change.

– brainstem herniation may also be apparent in severe cases.

– Posterior fossa appears small and shallow on imaging.

– MRI provides the definitive imaging but CT can also detect gross tonsillar herniation.

– Dynamic MRI in flexion and extension can assess degree of herniation.

– Upright MRI shows more tonsillar herniation than lying down position.

– Severity is graded based on degree of tonsillar descent relative to foramen magnum.

The dangerous area of the face refers to a region on the face which has a high risk of complications if infected due to its connections to the cranial cavity and brain.

The major features are:

– It is centered on the upper lip, extending from the corners of the mouth to the bridge of the nose.

– Infections here can spread to the cranial cavity via connecting veins and anatomical spaces.

– It contains angular, facial and ophthalmic veins which communicate directly with the cavernous sinus inside the skull.

– Thrombophlebitis of these veins can result in cavernous sinus thrombosis, a medical emergency.

– Infections like herpes, abscesses, or trauma to this area can spread posteriorly to cause meningitis, orbital cellulitis, sinus thrombosis, or brain abscess.

– The area is considered dangerous because the infections can rapidly reach the brain through the connecting venous drainage, made worse by lack of lymph nodes to filter bacteria.

– Immediate and aggressive antibiotic treatment is required for infections in this high-risk facial area to prevent severe complications.

– The angular, facial and ophthalmic veins that drain the dangerous facial area are valveless veins.

– This means that blood and infections can flow bidirectionally in these veins and spread in any direction.

– The angular vein connects to the cavernous sinus directly, while the facial vein connects to the angular vein.

– The ophthalmic vein connects via the superior ophthalmic vein to the cavernous sinus.

– These veins form a large anastomotic network due to their interconnections in the dangerous area of the face.

– The lack of valves combined with the anastomotic connections between these veins underlies the ability for rapid bidirectional spread of infection to the cavernous sinus and intracranial structures.

– Prompt recognition and management of infections in this area are vital to prevent potentially life-threatening complications.

Anatomy of the middle ear and internal acoustic meatus:

Middle Ear:

– Air-filled tympanic cavity located within the temporal bone.

– Contains the three ossicles – malleus, incus, and stapes.

– Ossicles transmit vibrations from the tympanic membrane to the oval window.

– Tympanic membrane forms the lateral boundary.

– Oval window and round window form medial boundaries.

– Eustachian tube connects the middle ear cavity to the nasopharynx.

– Facial nerve and chorda tympani nerve pass through the middle ear.

– Blood supply from internal carotid, maxillary and middle meningeal arteries.

Internal Acoustic Meatus:

– Opening in the posterior surface of the petrous portion of the temporal bone.

– Transmits the facial nerve, vestibulocochlear nerve, labyrinthine artery.

– CN VII passes through with nervus intermedius component.

– Vestibulocochlear nerve divides into cochlear and vestibular parts.

– Also contains superior and inferior vestibular nerves.

– Separated by a vertical crested ridge into anterior and posterior compartments.

– Perforated by small openings for passage of small nerves. (edited)

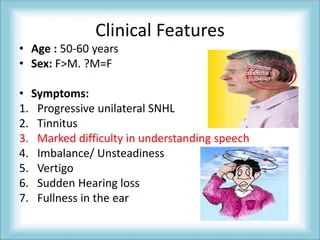

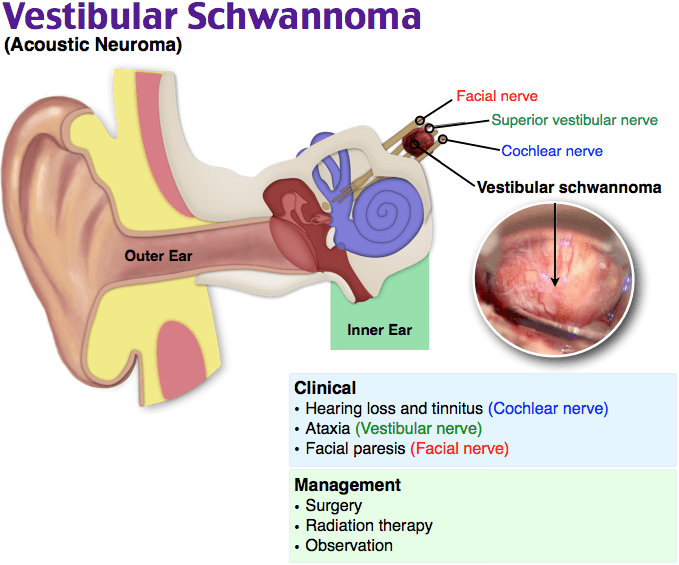

Vestibular schwannoma, also known as acoustic neuroma, is a benign tumor that arises from the Schwann cells of the vestibular nerve.

Origins:

– It originates from the nerve sheath cells (Schwann cells) that cover the vestibular portion of the vestibulocochlear nerve (8th cranial nerve).

– This nerve is responsible for hearing and balance.

– The tumor grows slowly over time and presses against the vestibulocochlear nerve, leading to symptoms.

Clinical Features:

– Unilateral hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo – These occur initially because the tumor compresses the cochlear and vestibular divisions of the vestibulocochlear nerve.

– Headache, facial numbness, weakness – Later symptoms as the tumor grows larger and compresses other nerves.

– Larger tumors can compress the brainstem and cerebellum.

The hyperacusis associated with vestibular schwannoma is actually due to damage or impairment of the stapedius muscle, resulting in stapedius muscle palsy.

The stapedius muscle is the smallest muscle in the body and is attached to the stapes bone in the middle ear. It normally contracts in response to loud sounds, reducing the transmission of sound waves to the inner ear. This protective acoustic reflex prevents excessively loud sounds from damaging the cochlea.

In vestibular schwannoma, the tumor can cause impairment of the facial nerve, which innervates the stapedius muscle. This leads to stapedius muscle palsy and inability to engage the acoustic reflex. As a result, patients experience hyperacusis or abnormal sensitivity to ordinary environmental sounds.

The confluence of sinuses, also known as the confluence of dural venous sinuses, refers to the joining of several major intracranial dural venous sinuses into a single structure.

Specifically, it is the joining of:

– Superior sagittal sinus

– Straight sinus

– Occipital sinus

– Two transverse sinuses

The transverse sinuses drain blood from the back of the head and brain, while the superior sagittal and straight sinuses drain from the front and top of the head.

The confluence of these venous sinuses forms a large venous structure known as the confluence of sinuses or torcular Herophili. It is located in the posterior cranial fossa, near the internal occipital protuberance of the skull.

From here, blood drains from the confluence of sinuses into the sigmoid sinuses and ultimately into the internal jugular veins.

The middle meningeal artery is a branch of the maxillary artery.

Specifically:

– The maxillary artery is the larger terminal branch of the external carotid artery.

– As the maxillary artery passes through the infratemporal fossa, it gives off several branches, including the middle meningeal artery.

– The middle meningeal artery courses upwards through the foramen spinosum of the sphenoid bone and enters the cranial cavity.

– It then travels through the dura mater and supplies blood to the bones and meninges of the brain.

– The middle meningeal artery is known to be injured in temporal bone fractures, leading to epidural hematoma.

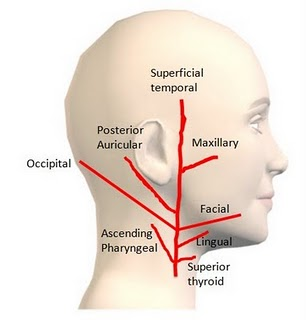

branches of external carotid artery and their supply with classifications

The external carotid artery has several branches that supply structures of the head, neck and face. These branches can be classified into:

Anterior Branches:

– Superior thyroid artery – Supplies thyroid gland, larynx, pharynx

– Lingual artery – Supplies tongue

– Facial artery – Supplies facial muscles, mouth, nose

Posterior Branches:

– Occipital artery – Supplies scalp over occiput

– Posterior auricular artery – Supplies scalp over ear, ear muscles

Terminal Branches:

– Maxillary artery – Supplies deep structures of face, mandible, teeth

– Superficial temporal artery – Supplies scalp over temple

Medial Branches:

– Ascending pharyngeal artery – Supplies pharynx, prevertebral muscles, middle ear

– Middle meningeal artery – Supplies dura mater, calvarial bones

The cavernous sinuses drain blood from several important structures in the brain:

– Orbit – The ophthalmic veins drain blood from the orbit and eye into the cavernous sinuses.

– Brain – Venous blood from the inferior parts of the frontal and temporal lobes drain into the cavernous sinuses.

– Pituitary gland – The inferior hypophyseal veins drain the pituitary gland into the cavernous sinuses.

– Brainstem – Some veins from the midbrain and pons also drain into the cavernous sinuses.

– Facial veins – The inferior ophthalmic vein, sphenoparietal sinus and pterygoid plexus drain blood from the face into the cavernous sinuses.

– Superficial cortical veins – Small veins from the medial sides of the cerebral hemispheres also drain into the cavernous sinuses.

Cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) is a rare but serious condition that occurs when a blood clot forms in the cavernous sinuses – a network of veins that drain blood from the brain and eyes.

Causes

– Infection – CST often starts with an infection in the face or skull such as sinusitis, dental abscess, cellulitis of the face, etc. Infection can spread to the cavernous sinuses through veins.

– Facial trauma

– Neurosurgery

Symptoms and Signs

– Headache and fever – Common early symptoms

– Periorbital edema – Swelling around the eyes

– Proptosis – Bulging of the eyes due to increased pressure

– Ocular palsies – Paralysis of the cranial nerves controlling eye movement, causing diplopia.

– Decreased vision or blindness

– Retro-orbital pain with eye movement

– Dilated, fixed pupil

– Cranial nerve palsies – CN III, IV, VI most commonly affected. Can also affect V and VIII.

– Signs of infection like high WBC count

– Seizures and focal neurological deficits if thrombosis spreads to brain.

Diagnosis is made by MRI/MRV, CT scan or angiography showing clot in cavernous sinus. Treatment involves antibiotics if infection, anticoagulants, and sometimes surgical drainage. Delays can result in permanent vision loss, stroke or death.

Some common benign tumors that can occur in the posterior cranial fossa include:

– Vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuroma) – Schwann cell tumor arising from the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII). Can cause hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo.

– Meningioma – Tumor of the meninges. Often arise from the tentorium cerebelli in the posterior fossa. Can compress cerebellum and brainstem.

– Epidermoid cyst – Congenital cyst lined by stratified squamous epithelium. Derived from ectoderm. Slow growing and can become large before causing symptoms.

– Hemangioblastoma – Vascular tumor arising from blood vessels. Associated with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Often found in the cerebellum.

– Craniopharyngioma – Benign tumor derived from Rathke’s pouch remnants. More common in suprasellar region but can occur in posterior fossa.

– Schwannoma of other cranial nerves – Can arise from CN IX, X, XI.

– Pituitary adenoma – Benign tumor of the pituitary gland. Most located in sella turcica but some posterior fossa extension.

– Low grade glial/astrocytic tumors (WHO Grade I or II) – Often pilocytic astrocytoma or subependymal giant cell astrocytoma.

– Choroid plexus papilloma – Benign tumor of choroid plexus tissue.

– Superior sagittal sinus – Runs along the attached margin of the falx cerebri, from front to back along the medial line of the skull. Connects to right and left transverse sinuses.

– Inferior sagittal sinus – Smaller sinus runs along the free margin of the falx cerebri. Joins the great cerebral vein to form the straight sinus.

– Straight sinus – Runs inferiorly along the junction of the falx cerebri and tentorium cerebelli. Joins the superior sagittal sinus with the confluence of sinuses.

– Transverse sinuses – Run laterally along the attached margins of the tentorium cerebelli on each side. Curve down to join the sigmoid sinuses.

– Sigmoid sinuses – S-shaped, run forward then down on each side. Receive transverse sinus and become internal jugular veins.

– Cavernous sinuses – Irregular venous networks on either side of the sella turcica, around the pituitary gland. Connect to each other, join the inferior and superior petrosal sinuses.

– Occipital sinus – Small sinus along the attached margin of the falx cerebelli, opens into confluence of sinuses.

– Confluence of the sinuses – Where the superior sagittal, straight, and transverse sinuses meet at the internal occipital protuberance.

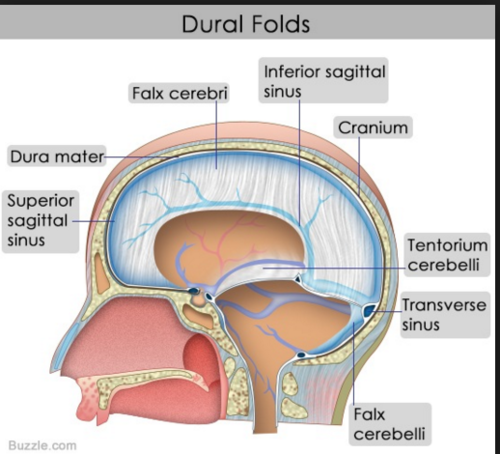

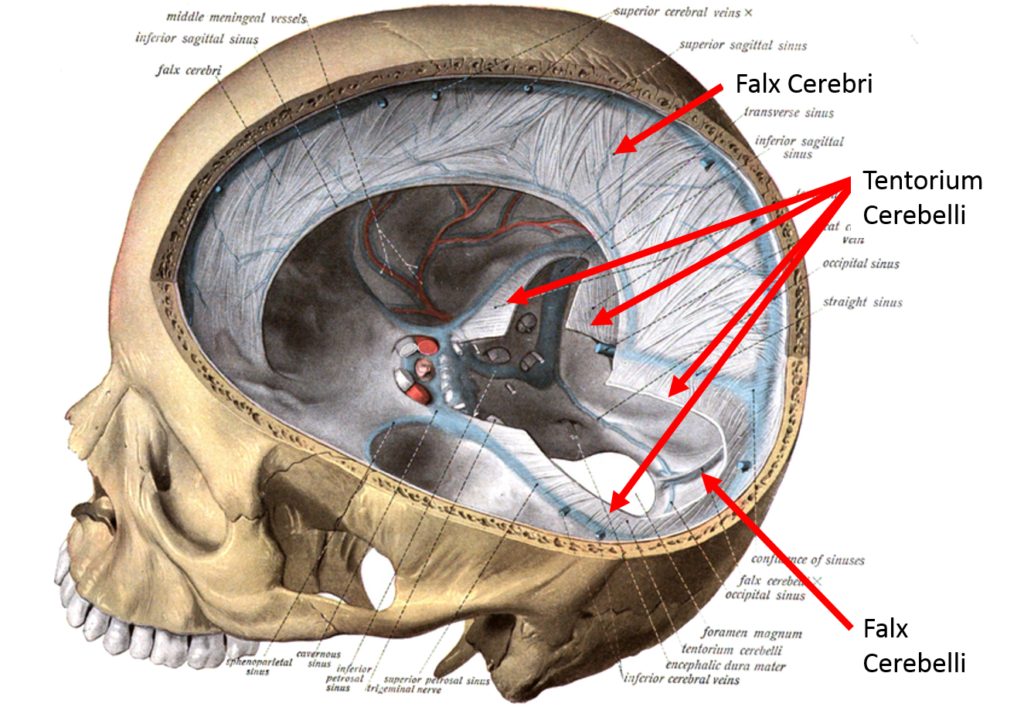

Here are the major dural folds and partitions in the brain?

– Falx cerebri – Attached to the skull vault along the longitudinal fissure, separates the left and right cerebral hemispheres.

– Tentorium cerebelli – Separates the cerebrum from the cerebellum and brainstem. Covers the posterior cranial fossa.

– Falx cerebelli – Vertical partition between the cerebellar hemispheres. Attached to posterior surface of foramen magnum.

– Diaphragma sellae – Covers the pituitary gland within the sella turcica. Has opening for infundibulum.

– Falx inguinalis – Vertical partition in the inguinal canal. Attaches to the pubic crest and lacunar ligament.

– Sinuses – Channels for venous blood to drain from brain. Located between layers of dura mater.

– Superior sagittal sinus – Runs along falx cerebri.

– Transverse, sigmoid sinuses – Along tentorium cerebelli.

– Occipital sinus – Along falx cerebelli.

– Cavernous sinuses – On either side of the sella turcica.

So the major dural folds include vertical partitions like the falx cerebri and cerebelli, the horizontal tentorium cerebelli, and the diaphragma sellae. Venous sinuses like the sagittal and transverse run along these folds.

Superior sagittal sinus – Runs along falx cerebri. Drainage: Primarily to the right transverse sinus, with some drainage to the confluence of sinuses.

– Inferior sagittal sinus – Runs along free edge of falx cerebri. Drainage: Joins great cerebral vein to form straight sinus.

– Straight sinus – Runs along the junction of falx cerebri and tentorium cerebelli. Drainage: Continues as left transverse sinus.

– Transverse sinuses – Run along the attached margins of tentorium cerebelli. Drainage: Curve inferiorly and continue as sigmoid sinuses.

– Sigmoid sinuses – S-shaped, run forward then down on each side. Drainage: Become internal jugular veins on each side.

– Occipital sinus – Runs along falx cerebelli. Drainage: Joins the confluence of sinuses.

– Cavernous sinuses – On either side of sella turcica. Drainage: Connect to each other, join inferior/superior petrosal sinuses.

– Confluence of sinuses – Meeting of sagittal/straight/transverse sinuses. Drainage: Primarily into the right transverse sinus.

Superior sagittal sinus:

– Receives blood from superficial cerebral veins

– Drains predominantly into the right transverse sinus

– Also drains into the confluence of sinuses

Inferior sagittal sinus:

– Receives blood from veins of corpus callosum

– Joins with great cerebral vein to form straight sinus

Straight sinus:

– Formed by junction of inferior sagittal and great cerebral vein

– Continues posteriorly as the left transverse sinus

Transverse sinuses:

– Receive blood from superficial cerebellar veins

– Right transverse sinus receives blood from superior sagittal sinus and confluence

– Left transverse receives blood from straight sinus

– Both transverse sinuses curve inferiorly to become sigmoid sinuses

Sigmoid sinuses:

– Drain blood from transverse sinuses

– Become continuous with internal jugular veins

Occipital sinus:

– Runs along falx cerebelli

– Drains into confluence of sinuses

Cavernous sinuses:

– Receive blood from ophthalmic veins, sphenoparietal sinus, superficial middle cerebral vein

– Connect to each other via intercavernous sinuses

– Drain into inferior and superior petrosal sinuses

Confluence of sinuses:

– Meeting point of superior sagittal, straight, and transverse sinuses

– Blood drains predominantly into right transverse sinus

The stylomastoid foramen is an opening located between the styloid and mastoid processes of the temporal bone. Here are the important structures that pass through the stylomastoid foramen:

– Facial nerve (CN VII) – This is the main structure that passes through the stylomastoid foramen. The facial nerve exits the skull through this opening after looping around the nucleus in the facial canal.

– Stylomastoid artery – Branch of the posterior auricular artery that enters the cranium through the stylomastoid foramen to supply the facial nerve, middle ear, and mastoid air cells.

– Auricular branch of vagus nerve (Arnold’s nerve) – Sensory branch of the vagus nerve that passes through the stylomastoid foramen to supply part of the outer ear.

– Venous drainage – Small veins from the tympanic cavity, facial nerve canal and dura mater may drain through the stylomastoid foramen into the external ju

csf flow in detail with all foramen?

Choroid plexus:

– Produces CSF in the lateral, third, and fourth ventricles

Foramen of Monro – Interventricular foramen

– Connects lateral ventricles to third ventricle

– Allows CSF flow from lateral to third ventricle

Foramen of Magendie – Median aperture

– Located at the lower posterior part of the fourth ventricle

– Main passageway for CSF exit from ventricles into subarachnoid space

Foramina of Luschka – Lateral apertures

– Located at sides of fourth ventricle

– Additional openings for CSF to exit fourth ventricle

Subarachnoid space

– Site of CSF circulation and reabsorption

– CSF flows over brain and spinal cord

Arachnoid granulations

– Projections of arachnoid membrane into dural venous sinuses

– Allow CSF reabsorption into bloodstream

Foramen ovale

– Opening in sphenoid bone of middle cranial fossa

– Site for CSF absorption into pterygoid plexus

CSF is produced by the choroid plexus in the lateral, third, and fourth ventricles.

Flow through ventricles:

– lateral ventricles > interventricular foramen (of Monro) > third ventricle

– third ventricle > cerebral aqueduct (of Sylvius) > fourth ventricle

Flow from fourth ventricle:

– Paired lateral apertures (of Luschka) > pontine cisterns

– Median aperture (of Magendie) > cisterna magna

Subarachnoid space flow:

– Basal cisterns > subarachnoid space over brain and spinal cord

– Arachnoid granulations > drainage into dural venous sinuses

The transverse sinuses are called so because they run transversely, side to side across the back of the cranium. Specifically:

– They are located along the attached margins of the tentorium cerebelli on each side.