Triangles of Neck & Contents

A 25 years old girl presents to your surgical out-door with the complain of gradual increase of a non-tender swelling in the middle of the anterior part of her neck over the period of 6 months. On examination you notice mass moves upwards during swallowing.

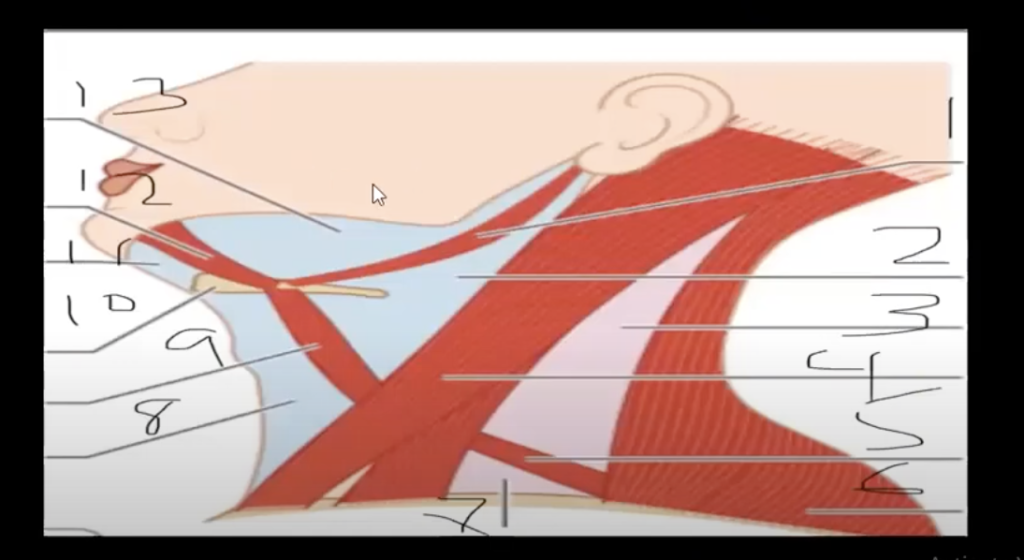

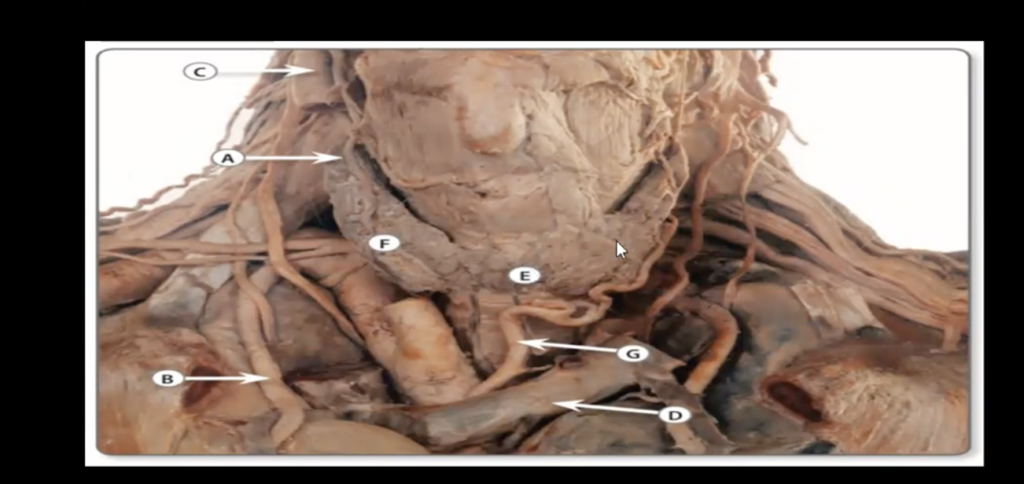

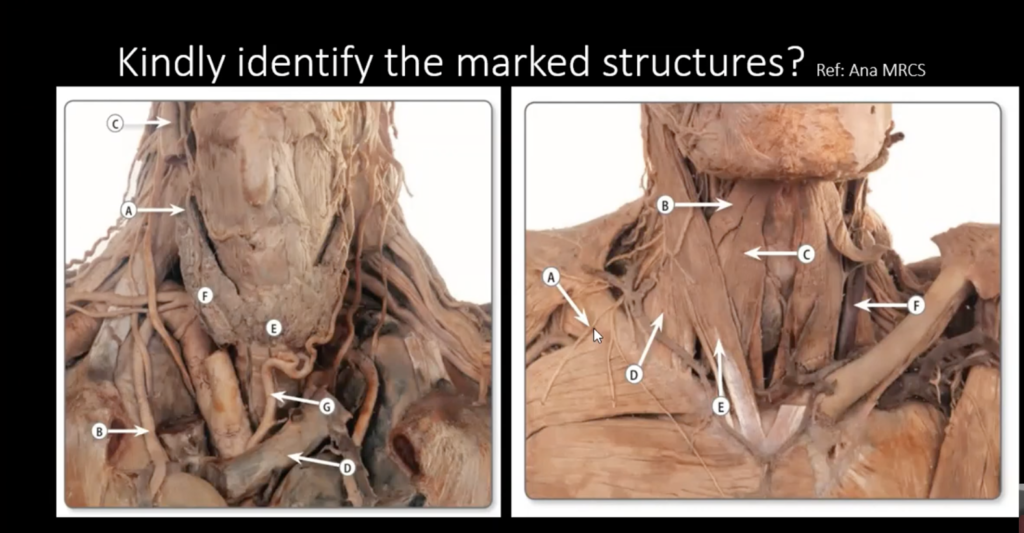

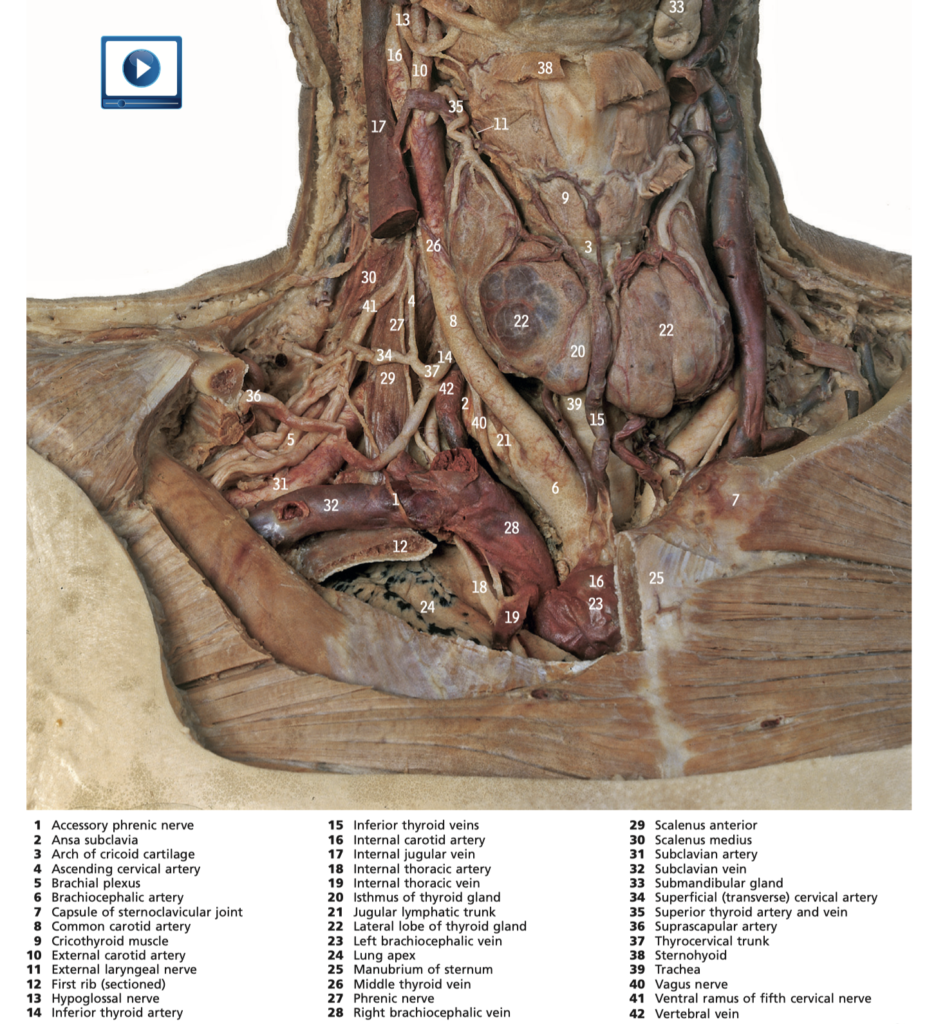

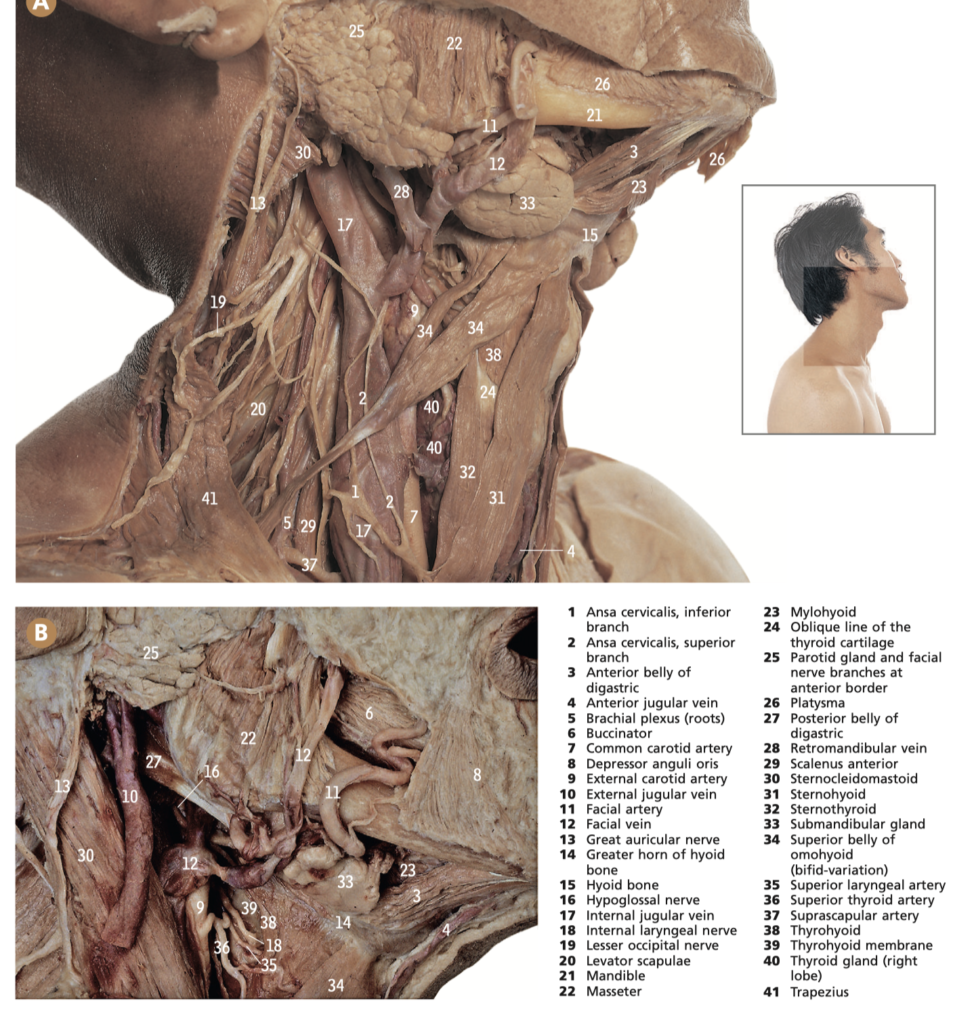

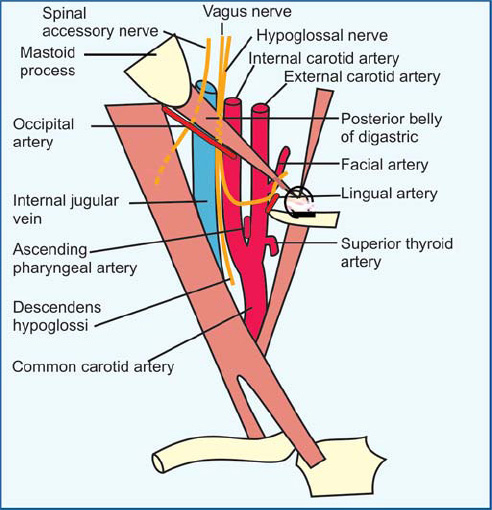

Consider this surgical anatomy station where you will be asked to identify the marked structures and hereby your knowledge will be evaluated ?

Q. Identify the marked areas?

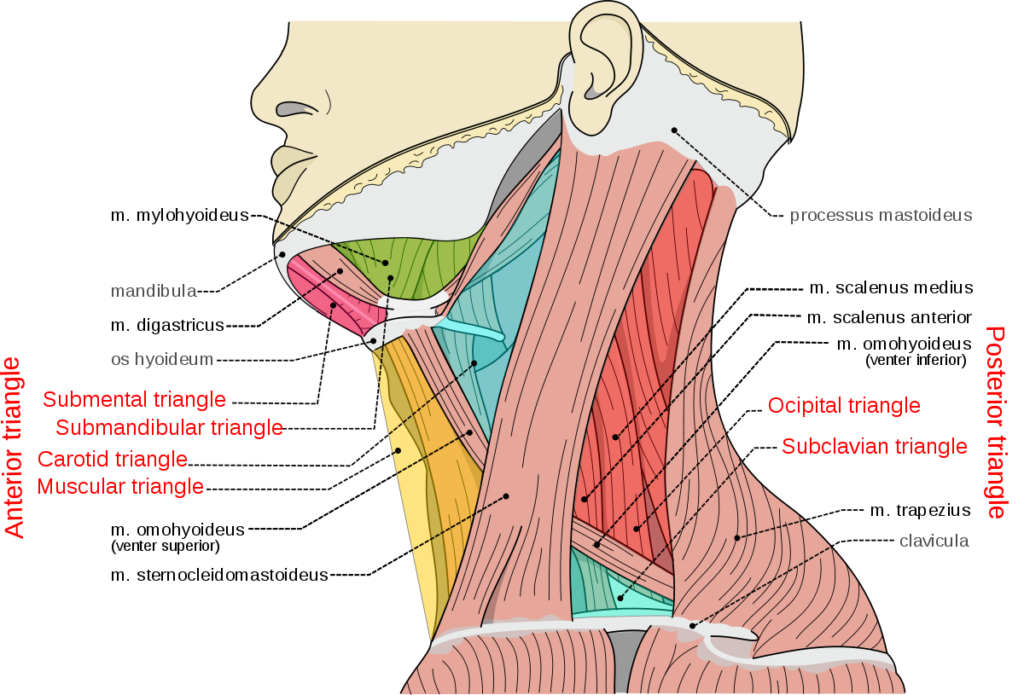

The triangles of the neck are six anatomical regions defined by their boundaries, contents, and divisions. They are important because they contain various structures such as blood vessels, nerves, and glands. Here is a more detailed description of each triangle, its boundaries, contents, and divisions:

- Anterior Triangle:

- Boundaries: The anterior triangle is bounded by the anterior midline of the neck, the lower border of the mandible, and the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

- Contents: The anterior triangle contains the submandibular gland, submental lymph nodes, common carotid artery, internal jugular vein, vagus nerve, hypoglossal nerve, lingual nerve, and facial artery.

- Divisions: The anterior triangle is further divided into four smaller triangles: submental triangle, submandibular triangle, carotid triangle, and muscular triangle.

- Posterior Triangle:

- Boundaries: The posterior triangle is bounded by the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the anterior border of the trapezius muscle, and the middle third of the clavicle.

- Contents: The posterior triangle contains the accessory nerve (CN XI), brachial plexus, cervical plexus, external jugular vein, subclavian artery and vein, transverse cervical artery, and suprascapular artery.

- Divisions: The posterior triangle is further divided into two smaller triangles: occipital triangle and supraclavicular triangle.

- Submental Triangle:

- Boundaries: The submental triangle is located under the chin and is bounded by the anterior belly of the digastric muscle and the hyoid bone.

- Contents: The submental triangle contains submental lymph nodes, submental artery and vein, and mylohyoid nerve.

- Submandibular Triangle:

- Boundaries: The submandibular triangle is located below the mandible and is bounded by the inferior border of the mandible, the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle, and the stylohyoid muscle.

- Contents: The submandibular triangle contains the submandibular gland, submandibular lymph nodes, facial artery, lingual artery, hypoglossal nerve, and submental artery and vein.

- Carotid Triangle:

- Boundaries: The carotid triangle is located on the side of the neck and is bounded by the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the superior belly of the omohyoid muscle.

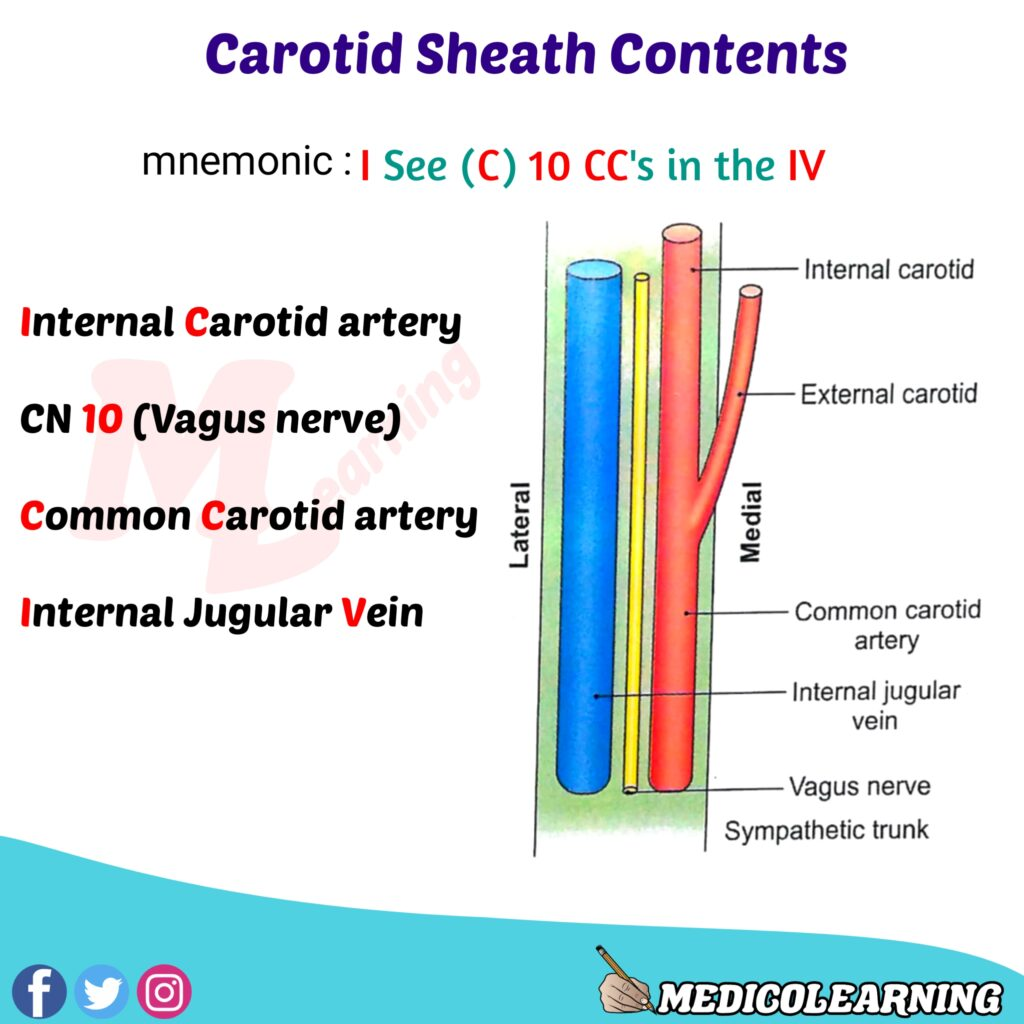

- Contents: The carotid triangle contains the common carotid artery, internal jugular vein, vagus nerve, hypoglossal nerve, sympathetic trunk, carotid body and sinus, and deep cervical lymph nodes.

- Muscular Triangle:

- Boundaries: The muscular triangle is located on the side of the neck and is bounded by the superior belly of the omohyoid muscle, the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the median plane of the neck.

- Contents: The muscular triangle contains the infrahyoid muscles, thyroid gland, parathyroid glands, recurrent laryngeal nerve, and inferior thyroid artery and vein.

Q. significance of posterior triangles of neck?

Neurovascular structures: The posterior triangle contains important neurovascular structures such as the accessory nerve (CN XI), brachial plexus, cervical plexus, and the transverse cervical artery and vein. These structures are at risk during various surgical procedures, including neck dissections, and injuries to these structures can result in significant morbidity.

Lymphatic drainage: The posterior triangle contains lymph nodes that drain lymphatic fluid from the scalp, neck, and upper extremities. These lymph nodes can be affected by various conditions such as infections, tumors, and inflammatory diseases.

Surgical access: The posterior triangle provides access to various structures in the neck, including the carotid artery, subclavian artery and vein, and the brachial plexus. This makes the posterior triangle an important region for surgical exposure and access during various surgical procedures such as neck dissections, thyroidectomies, and cervical spine surgeries.

Clinical conditions: Several clinical conditions can affect the posterior triangle, including tumors, lymphadenopathy, and infections. These conditions can present with various symptoms such as neck pain, swelling, and restriction of neck movements.

Anatomical landmarks: The boundaries of the posterior triangle can serve as important anatomical landmarks for identifying structures in the neck. For example, the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is used to locate the accessory nerve, and the anterior border of the trapezius muscle is used to locate the cervical plexus.

Q. list all the contents of each triangles?

The contents of the triangles of the neck vary depending on the specific triangle. Here is a brief overview of the contents of each triangle:

- Anterior triangle: This triangle contains the following structures:

- Submandibular gland

- Submental lymph nodes

- Common carotid artery

- Internal jugular vein

- Vagus nerve

- Hypoglossal nerve

- Lingual nerve

- Facial artery

- Posterior triangle: This triangle contains the following structures:

- Accessory nerve (CN XI)

- Brachial plexus

- Cervical plexus

- External jugular vein

- Subclavian artery and vein

- Transverse cervical artery

- Suprascapular artery

- Submental triangle: This triangle contains the following structures:

- Submental lymph nodes

- Submental artery and vein

- Mylohyoid nerve

- Submandibular triangle: This triangle contains the following structures:

- Submandibular gland

- Facial artery

- Lingual artery

- Hypoglossal nerve

- Submandibular lymph nodes

- Submental artery and vein

- Carotid triangle: This triangle contains the following structures:

- Common carotid artery

- Internal jugular vein

- Vagus nerve

- Hypoglossal nerve

- Sympathetic trunk

- Carotid body and sinus

- Deep cervical lymph nodes

- Muscular triangle: This triangle contains the following structures:

- Infrahyoid muscles

- Thyroid gland

- Parathyroid glands

- Recurrent laryngeal nerve

- Inferior thyroid artery and vein

It is important to note that there may be variations in the contents of each triangle, and some structures may be absent or present in different individuals. Additionally, certain pathologies or conditions may affect the structures within these triangles and alter their contents.

Q. origin and insertion and nerve supply of all muscles involved in these triangles?

There are several muscles that are involved in the triangles of the neck. Here is a list of these muscles along with their origin, insertion, and nerve supply:

- Sternocleidomastoid muscle:

- Origin: The sternocleidomastoid muscle originates from the sternum and clavicle.

- Insertion: The muscle inserts on the mastoid process of the temporal bone and the superior nuchal line of the occipital bone.

- Nerve supply: The sternocleidomastoid muscle is innervated by the accessory nerve (CN XI).

- Trapezius muscle:

- Origin: The trapezius muscle originates from the occipital bone, ligamentum nuchae, and the spinous processes of C7-T12 vertebrae.

- Insertion: The muscle inserts on the spine of the scapula, acromion, and the lateral third of the clavicle.

- Nerve supply: The trapezius muscle is innervated by the accessory nerve (CN XI).

- Digastric muscle:

- Origin: The anterior belly of the digastric muscle originates from the digastric fossa of the mandible, while the posterior belly originates from the mastoid process of the temporal bone.

- Insertion: Both bellies of the muscle insert on a common intermediate tendon that attaches to the hyoid bone.

- Nerve supply: The anterior belly is innervated by the mylohyoid nerve (a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve – CN V3), while the posterior belly is innervated by the facial nerve (CN VII).

- Omohyoid muscle:

- Origin: The superior belly of the omohyoid muscle originates from the intermediate tendon, while the inferior belly originates from the scapula.

- Insertion: The muscle inserts on the hyoid bone.

- Nerve supply: The omohyoid muscle is innervated by the ansa cervicalis, which is a loop of nerves formed by branches of the cervical spinal nerves C1-C3.

- Infrahyoid muscles (Sternohyoid, Omohyoid, Sternothyroid, Thyrohyoid):

- Origin: The infrahyoid muscles have various origins, including the sternum, clavicle, scapula, and thyroid cartilage.

- Insertion: The muscles insert on the hyoid bone or the thyroid cartilage.

- Nerve supply: The infrahyoid muscles are innervated by the ansa cervicalis.

- Scalene muscles (Anterior, Middle, Posterior):

- Origin: The scalene muscles originate from the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae (C2-C7).

- Insertion: The muscles insert on the first and second ribs.

- Nerve supply: The anterior and middle scalene muscles are innervated by the cervical spinal nerves (C4-C6), while the posterior scalene muscle is innervated by the cervical spinal nerve (C8) and the first thoracic spinal nerve (T1).

- Laryngeal muscles (Thyroarytenoid, Cricothyroid, Posterior cricoarytenoid, lateral cricoarytenoid, oblique and transverse arytenoid muscles):

- Origin: The laryngeal muscles have various origins, including the thyroid and cricoid cartilages.

- Insertion: The muscles insert on the arytenoid cartilages and the vocal folds.

- Nerve supply: The laryngeal muscles are innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which is a branch of the vagus nerve (CN X).

It is important to note that some of these muscles may have additional functions or attachments beyond the triangles of the neck, and that there may be variations in the nerve supply and attachments of these muscles in different individuals.

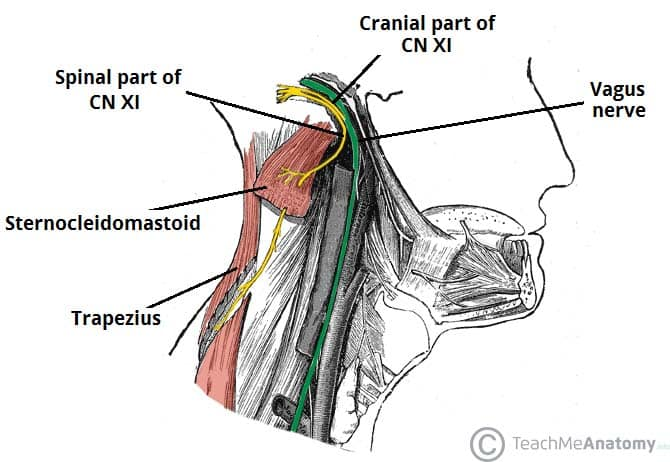

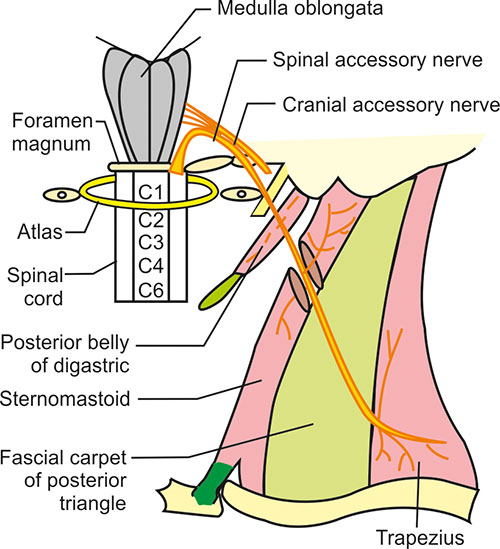

Q. spinal accessory nerve and its supply and injury details

Spinal accessory nerve (CN XI) has the following anatomy and clinical significance:

The spinal accessory nerve (CN XI) is a motor nerve that innervates the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. It originates from the spinal cord segments C1-C5 and exits the skull through the jugular foramen along with the glossopharyngeal (CN IX) and vagus (CN X) nerves.

The spinal accessory nerve supplies the following muscles:

- Sternocleidomastoid muscle: The spinal accessory nerve supplies the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which is responsible for rotating the head to the opposite side and flexing the neck.

- Trapezius muscle: The spinal accessory nerve supplies the trapezius muscle, which is responsible for elevating, retracting, and rotating the scapula.

Injury to the spinal accessory nerve can occur due to various causes such as trauma, surgical procedures, or tumors. The symptoms of spinal accessory nerve injury depend on the degree and location of the injury. Here are some of the common symptoms associated with spinal accessory nerve injury:

- Weakness or paralysis of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles, which can cause difficulty in rotating the head, flexing the neck, and raising the shoulder.

- Shoulder droop or winging, which occurs due to weakness of the trapezius muscle and can result in reduced shoulder stability and function.

- Pain and discomfort in the neck and shoulder region, which can occur due to compensatory muscle tension and altered posture.

- Difficulty in raising the arm above the head, which can occur due to reduced stability and function of the shoulder joint.

Treatment for spinal accessory nerve injury depends on the severity and location of the injury. Mild cases may resolve on their own with time and physical therapy, while more severe cases may require surgery or other interventions.

Q. course of spinal accessory nerve?

The spinal accessory nerve (CN XI) is a motor nerve that originates from the spinal cord and has a complex course through the neck and shoulder region. Here is the course of the spinal accessory nerve:

- Origin: The spinal accessory nerve originates from the spinal cord segments C1-C5 in the upper cervical region.

- Exit: The spinal accessory nerve exits the skull through the jugular foramen, which is a bony opening located at the base of the skull.

- Course in the neck: After exiting the skull, the spinal accessory nerve descends along the internal jugular vein in the carotid sheath. It then enters the sternocleidomastoid muscle and divides into several branches that innervate the muscle fibers.

- Course in the shoulder: The spinal accessory nerve then passes through the posterior triangle of the neck and enters the trapezius muscle. It divides into several branches that innervate the muscle fibers of the trapezius muscle.

- Termination: The spinal accessory nerve ultimately terminates in the upper fibers of the trapezius muscle.

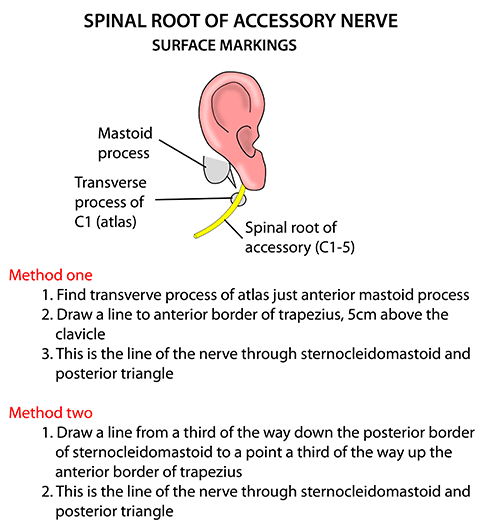

Q.surface marking of spinal accessory nerve ( rule of third)?

One of the methods for surface marking of the spinal accessory nerve is the “rule of thirds”. Here’s how it works:

- Divide the sternocleidomastoid muscle into thirds: Using the fingers, divide the sternocleidomastoid muscle into three equal parts: upper, middle, and lower thirds.

- Identify the point of intersection with the trapezius muscle: At the point where the upper third of the sternocleidomastoid muscle intersects with the trapezius muscle, the spinal accessory nerve is located.

- Trace the nerve posteriorly: From the point of intersection, trace the spinal accessory nerve posteriorly towards the trapezius muscle.

- Confirm the location of the nerve: The spinal accessory nerve can be confirmed by asking the patient to shrug their shoulders or rotate their head against resistance. This will cause contraction of the trapezius muscle, which is innervated by the spinal accessory nerve

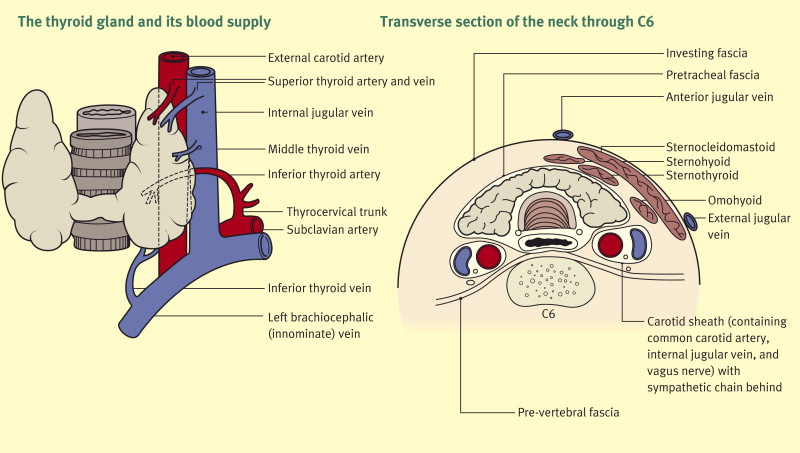

Q. structures at the level of C6?

The following important structures are located at the level of the C6 vertebra:

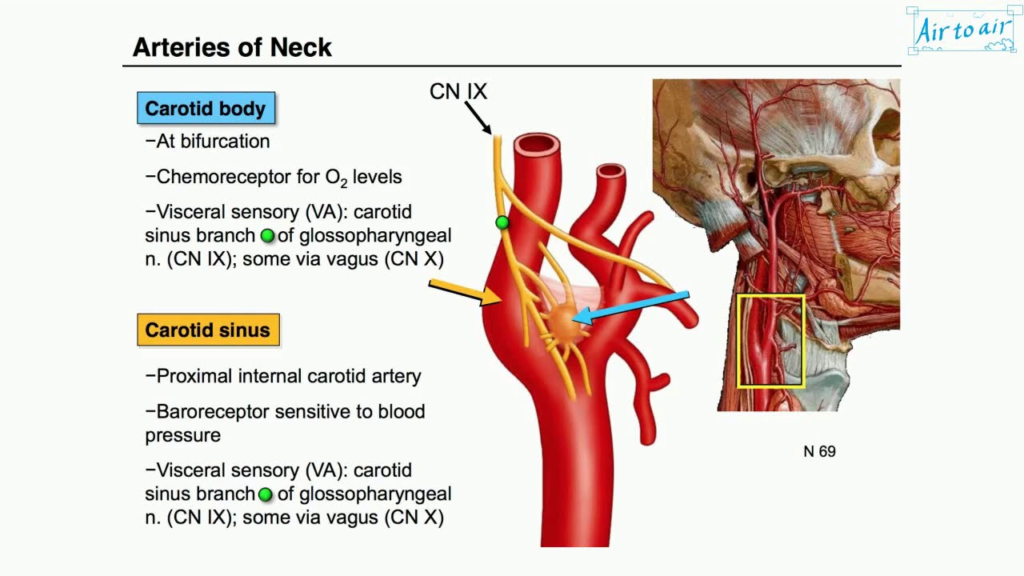

1. Carotid sinus: The carotid sinus is a dilation of the internal carotid artery at its origin just above the bifurcation of the common carotid artery. It contains baroreceptors sensitive to arterial blood pressure changes. The carotid sinus is located posterior to the anterior border of sternocleidomastoid at the level of C6.

2. Carotid bifurcation: The common carotid artery bifurcates into the internal and external carotid arteries at the level of C6. The internal carotid continues cranially into the skull, while the external carotid supplies the face, scalp and neck.

3. Ansa cervicalis: The ansa cervicalis is a loop of nerves formed by the ventral rami of C1-C3. It descends anterior to the carotid sheath and provides motor innervation to the infrahyoid strap muscles of the neck. The ansa cervicalis crosses the common carotid artery at C6.

4. Carotid sheath: The carotid sheath contains the common carotid artery, internal jugular vein and vagus nerve. It is located lateral to the visceral fascia in the neck with the common carotid artery lying most medially, then the internal jugular vein and vagus nerve laterally.

5. Vagus nerve: Within the carotid sheath, the vagus nerve descends into the thorax to provide parasympathetic innervation to the viscera. It gives off branches including the superior laryngeal nerve before passing posterior to the internal jugular vein at C6.

6. Ansa cervicalis branches: Branches from the ansa cervicalis innervate the infrahyoid muscles at C6, including the sternohyoid, sternothyroid, thyrohyoid and superior belly of omohyoid.

7. Chassaignac’s tubercle: The transverse process of C6 vertebra, known as Chassaignac’s tubercle, is a useful superficial anatomical landmark located in the posterior triangle of the neck. The spinal accessory nerve passes just superior to this tubercle.

8. Superficial cervical lymph nodes: Along the posterior border of sternocleidomastoid, superficial lymph nodes draining the face, neck, scalp and pharynx are located at the level of C6.

Many important neurovascular structures relay at or pass through the level of C6 in the neck. An understanding of the anatomy at this level is essential for both clinical examination of the neck as well as guidance during surgical procedures to avoid inadvertent damage to critical structures.

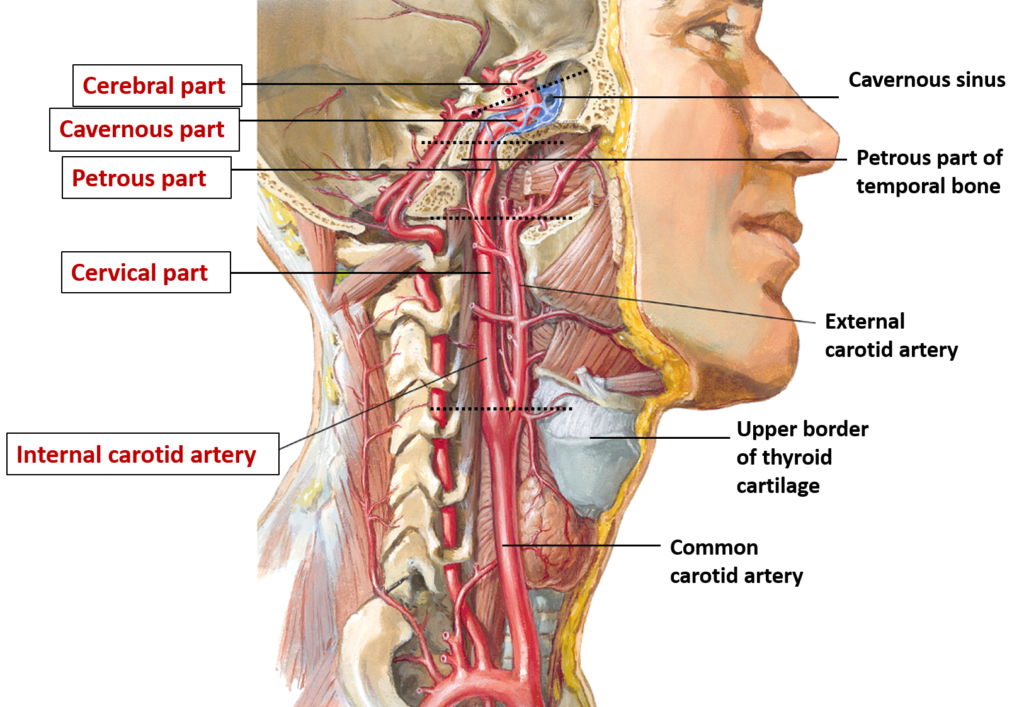

Q. Through where does internal carotid artery enter brain?

The internal carotid artery enters the base of the skull and supplies the brain as follows:

1. The internal carotid artery originates at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery in the neck, at the level of the 4th cervical vertebra. It has no branches in the neck.

2. The internal carotid enters the carotid canal in the temporal bone and travels forwards and medially. In the carotid canal, it gives off its first branch – the petrous branch to the middle ear.

3. The internal carotid then emerges from the temporal bone into the cranial cavity via the foramen lacerum. It is accompanied through the foramen lacerum by the sympathetic plexus around it and the meningeal branch of maxillary artery.

4. In the middle cranial fossa, the internal carotid gives off the following branches:

– Vidian artery: Accompanies the vidian nerve through the pterygoid canal

– Caroticotympanic artery: Supplies the middle ear

– Artery of pterygoid canal: Supplies the tensor veli palatini muscle

5. The internal carotid then passes through the cavernous sinus lying lateral to the pituitary gland. In the cavernous sinus, it gives off the meningohypophyseal arteries which supply the pituitary gland and parts of the meninges.

6. The internal carotid pierces the dura at the foramen lacerum and enters the subarachnoid space. It then divides into the anterior and middle cerebral arteries which supply blood to most of the supratentorial brain.

– The anterior cerebral artery supplies the medial surface of the frontal and parietal lobes.

– The middle cerebral artery is the largest branch and supplies the lateral surface of the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes including the motor and sensory cortices.

7. At the level of its bifurcation within the subarachnoid space, the internal carotid also gives rise to the posterior communicating artery which helps form the posterior circulation of the brain.

The internal carotid artery has no branches in the neck. It gives off several small branches in the cranial cavity and major branches including the anterior, middle and posterior cerebral arteries to supply the brain. Blockage or rupture of the internal carotid can lead to stroke due to loss of blood supply to critical areas of the brain.

Q.Id the marked structures?

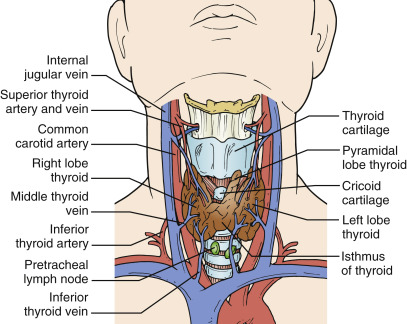

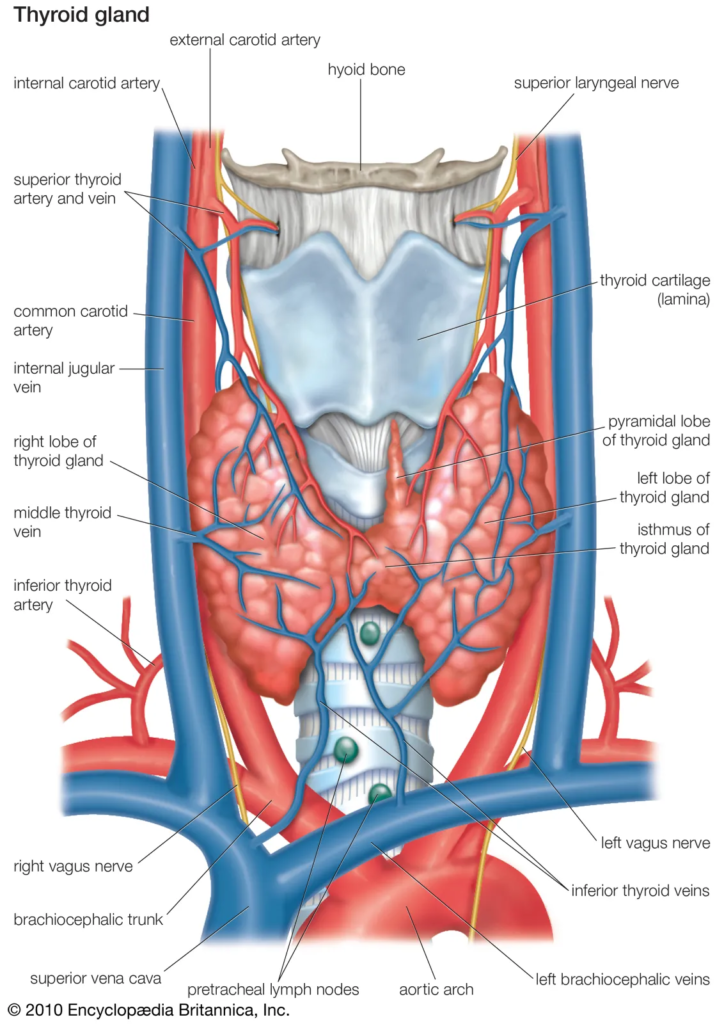

Q. Blood supply of thyroid?

The thyroid gland receives its blood supply from the following sources:

1. Superior thyroid artery: Arises from the external carotid artery in the neck. It descends anterior to the internal carotid artery and posterior to the infrahyoid strap muscles. The superior thyroid artery supplies the upper part of the thyroid lobes and the upper parathyroid glands.

2. Inferior thyroid artery: Arises from the thyrocervical trunk of the subclavian artery. It ascends anterior to the vertebral artery and posterior to the carotid sheath. The inferior thyroid artery supplies the lower part of the thyroid lobes and adjacent parathyroid glands.

3. Thyroid ima artery: An inconstant artery that arises from the brachiocephalic trunk or aortic arch. It ascends in front of the trachea to supply the upper part of the thyroid gland. Reported in up to 65% of individuals.

4. Parathyroid arteries: Small arteries that arise from the inferior thyroid arteries or directly from the thyrocervical trunk to supply the parathyroid glands. Maintaining blood supply to the parathyroid glands is important during thyroid surgery to avoid hypoparathyroidism.

5. Laryngeal arteries: Branches from the superior and inferior thyroid arteries also supply blood to the larynx and upper trachea. The close anatomical relationship between the thyroid gland and laryngo-tracheal structures means they are often involved together in goitres and malignancies.

Venous drainage of the thyroid gland is via the superior, middle and inferior thyroid veins. The superior and middle veins drain into the internal jugular vein, while the inferior vein drains into the brachiocephalic vein.

The arterial supply of the thyroid gland is from branches of the external carotid artery (superior thyroid) and subclavian artery (inferior thyroid, thyroidea ima). The veins drain into the internal jugular and brachiocephalic veins. Understanding the blood supply of the thyroid gland is important when performing investigations like thyroid scintigraphy, and during surgery to avoid hemorrhage and damage to adjacent structures. Ligation of critical arteries and veins may be required in treatment of certain thyroid diseases.

Q. mode of spread of thyroid cancers?

The major thyroid cancers spread as follows:

1. Papillary thyroid cancer: Spreads primarily via lymphatic metastasis to regional cervical lymph nodes. This results in lymph node enlargement which is important for diagnosis and staging.

2. Follicular thyroid cancer: Usually spreads via the bloodstream, metastasizing to distant sites such as the lungs and bones. While follicular cancer can spread to lymph nodes, hematogenous spread is more characteristic. This results in lung metastasis and bone lesions rather than prominent lymphadenopathy.

3. Poorly differentiated cancers: Spread readily by both lymph node invasion as well as distant hematogenous metastasis. Aggressive disease and poor prognosis.

4. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: Rapid spread locally into neck structures as well as distant hematogenous metastasis. Poorly differentiated and anaplastic cancers behave the most aggressively.

5. Medullary thyroid cancer: Spreads more commonly through blood vessels rather than lymphatics. Liver, lungs and bones are frequent metastatic sites. Lymph node spread still occurs in about 50% of cases, however.

6. Thyroid lymphoma: Diffuse involvement of thyroid gland as well as local and distant spread. Hematological malignancy that behaves differently from epithelial thyroid cancers.

So in summary, while most thyroid cancers can spread to some degree via both lymphatic and hematogenous routes, the patterns of predominance are:

– Papillary: Primarily lymphatic

– Follicular: Primarily hematogenous

– Poorly differentiated and anaplastic: Rapid spread by both lymph and blood vessels

– Medullary: More commonly hematogenous

– Lymphoma: Systemic hematological spread

Q. where cricothyroidectomy is done?

A cricothyroidotomy is performed through the cricothyroid membrane in the median part of the neck. This membrane spans between the cricoid cartilage below and thyroid cartilage above.

Anatomy relevant to cricothyroidotomy:

1. Cricoid cartilage: The only complete ring in the trachea. It sits below the thyroid cartilage and cricothyroid membrane, at the commencement of the trachea. The cricothyroidotomy incision passes through the upper part of the cricoid cartilage.

2. Thyroid cartilage: Consists of two laminae that fuse anteriorly at an acute angle to form the laryngeal prominence (Adam’s apple). The cricothyroid membrane spans between the inferior border of the thyroid cartilage and the cricoid cartilage.

3. Cricothyroid membrane: A dense fibroelastic membrane that connects the cricoid and thyroid cartilages. It is spanned by the cricothyroid muscles that act to change vocal cord tension. A cricothyroidotomy incision passes vertically through the middle portion of the cricothyroid membrane to access the airway below.

4. Arteria cricothyroidea: A small branch from the superior thyroid artery that supplies the cricothyroid membrane. It must be ligated or retracted during cricothyroidotomy to limit bleeding.

5. Vena cricothyroidea: The venous equivalent draining from the cricothyroid membrane into the internal jugular vein. Care must also be taken to limit venous bleeding during cricothyroidotomy.

6. Cricothyroid muscles: Span between the cricoid cartilage and thyroid cartilage, with attachments on either side of the cricothyroid membrane. They act to rotate the thyroid cartilage which alters vocal cord tension for phonation. These muscles are separated during cricothyroidotomy.

A cricothyroidotomy provides emergency airway access when the upper airway is obstructed. An incision is made vertically through the cricothyroid membrane between the cricoid ring below and thyroid cartilage above. Care must be taken to avoid damage to the cricothyroid arteries and veins, and separation rather than cutting of the cricothyroid muscles is preferred.A cricothyroidotomy is a lifesaving procedure performed as a last resort in a “can’t intubate, can’t oxygenate” scenario.

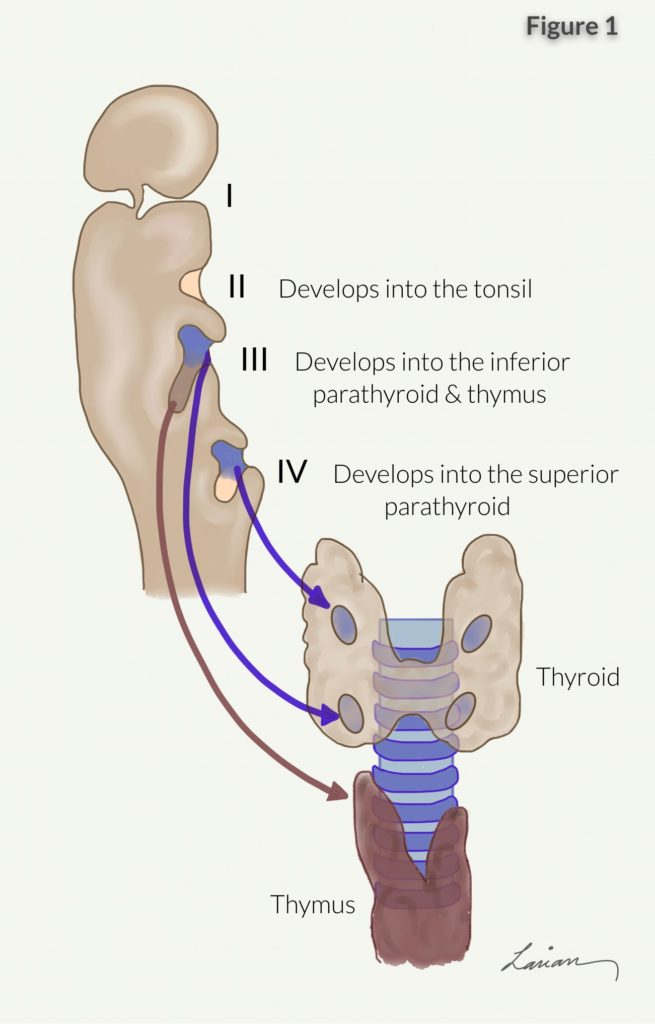

Q. how many parathyroid galand s and there proper location

There are typically four parathyroid glands located near the thyroid gland in the neck:

1. Superior parathyroid glands: Usually two glands located on the posterior surface of the upper thyroid lobes, near the junction of the upper and middle thirds of the thyroid gland. They are situated adjacent to the recurrent laryngeal nerves.

2. Inferior parathyroid glands: Usually two glands located on the posterior surface of the lower thyroid lobes, immediately lateral or inferior to the inferior thyroid artery. They are near the inferior thyroid vein and recurrent laryngeal nerve.

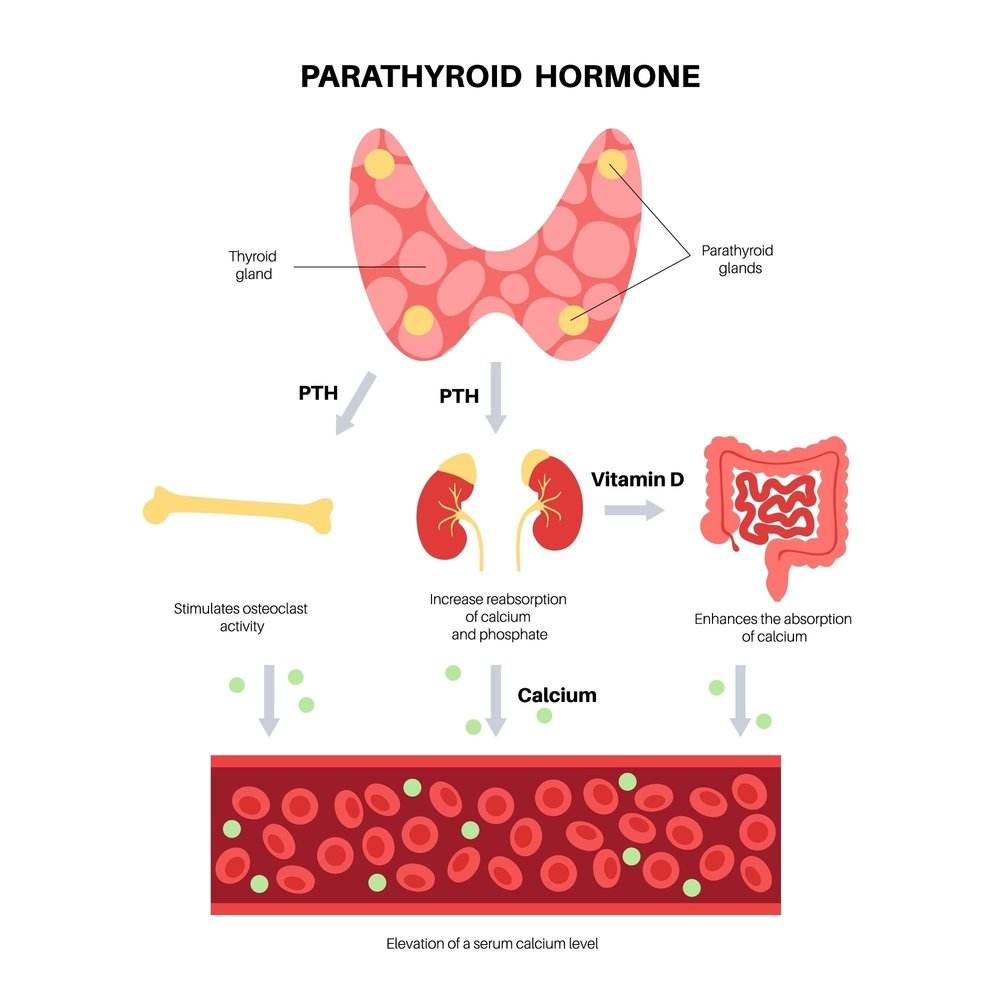

The parathyroid glands regulate calcium homeostasis in the body. They produce parathyroid hormone (PTH) which acts to increase serum calcium levels when detected as too low. The parathyroids respond to feedback from the calcium-sensing receptor.

In some cases, there may be additional or ectopic parathyroid glands:

– Supernumerary glands: Extra parathyroid glands (5 or more) which develop separately and function normally. Reported in up to 13% of individuals.

– Ectopic glands: Occur when one or more parathyroid glands fail to migrate to their usual location during development. Can occur anywhere along the path of descent from the base of the skull to the neck. Mediastinum and thymus are common sites.

– Hyperplastic glands: Enlargement of existing parathyroid glands due to excess stimulation over time. Associated with long standing hypocalcemia and secondary hyperparathyroidism.

The parathyroid glands are tiny, measuring only 3 to 8 mm, and vary in number and position between individuals. Their migration during development from the branchial arches sometimes results in ectopic locations, commonly in the thymus or anterior mediastinum.

Q. attachment of cricothyroid membrane?

The cricothyroid membrane attaches the cricoid cartilage below to the thyroid cartilage above. Specifically:

1. The inferior border of the cricothyroid membrane attaches to the superior border of the cricoid cartilage. The cricoid cartilage forms a complete ring at the commencement of the trachea, so the cricothyroid membrane seals off the airway above this level.

2. The superior border of the cricothyroid membrane attaches to the inferior border of the thyroid cartilage. The thyroid cartilage consists of two laminae that fuse anteriorly at an acute angle to form the laryngeal prominence.

3. On either side, the cricothyroid membrane spans laterally to attach to the inner surfaces of the cricoid and thyroid cartilages. These lateral attachments help stabilize the membrane.

4. The posterior portion of the cricothyroid membrane is attached to the anterior wall of the lower pharynx. This attachment provides further support and suspension for the laryngeal structures above.

5. The cricothyroid muscles attach on either side of the cricothyroid membrane. Though not directly attached to the membrane itself, the muscles provide support and also act to rotate the thyroid cartilage which alters vocal cord tension.

The dense, fibroelastic cricothyroid membrane provides an attachment point and support for structures involved in phonation and airway protection:

1. It attaches and helps suspend the thyroid cartilage which houses the vocal cords. Movements of the thyroid cartilage contribute to controlling vocal cord tension.

2. It seals off the subglottic airway below the level of the vocal cords, while still allowing mobility of the larynx required for speech and swallowing.

3. It provides an attachment point for the cricothyroid muscles on either side, which act to rotate the thyroid cartilage.

4. It protects the airway from foreign material entering from the esophagus behind.

The attachments of the cricothyroid membrane help maintain its position spanning between the cricoid and thyroid cartilages. Damage or weakness of these attachments can compromise its ability to provide support for phonation and airway protection. Surgical procedures like cricothyroidotomy also disrupt these attachments, though they can heal once the procedure site is closed.

Q.cartilages of larynx?

The cartilages of the larynx include:

1. Thyroid cartilage: The largest cartilage of the larynx. It consists of two laminae fusing anteriorly at an acute angle to form the laryngeal prominence (Adam’s apple). The thyroid cartilage protects the vocal cords and supports other laryngeal structures.

2. Cricoid cartilage: The only complete ring-shaped cartilage of the larynx. It forms the inferior wall of the larynx, with the esophagus passing behind it. The cricoid cartilage attaches to the first tracheal ring and provides support for the glottis above.

3. Arytenoid cartilages (paired): Pyramid-shaped cartilages located at the posterosuperior corners of the cricoid cartilage. The arytenoid cartilages provide attachment and mobility for the vocal cords. They rotate and glide during abduction and adduction of the vocal cords.

4. Corniculate cartilages (paired): Small conical cartilages located at the apices of the arytenoid cartilages. They continue the curve of the arytenoids posteriorly. The corniculate cartilages have little known function but are considered vestigial structures.

5. Cuneiform cartilages (paired): Tiny rod-shaped cartilages located in the aryepiglottic folds. They are not always present. The cuneiform cartilages have little known purpose but are thought to provide support for the aryepiglottic folds.

6. Epiglottis: Leaf-shaped elastic cartilage behind the tongue and hyoid bone. The epiglottis covers the glottis during swallowing to direct food into the esophagus. It is attached to the inner surface of the thyroid cartilage and provides lid-like protection of the airway entrance.

The laryngeal cartilages provide a rigid framework for the walls and entrance of the larynx:

– The thyroid, cricoid and epiglottis cartilages form the anterior, lateral and posterior walls respectively.

– The arytenoid and corniculate cartilages provide mobility and support for the vocal cords.

– The cuneiform cartilages have a minor supporting role in the aryepiglottic folds.

The cartilages allow laryngeal mobility required for speech, swallowing and airway protection. Damage or calcification of the cartilages can impair laryngeal function, necessitating procedures like epiglottidoplasty, arytenoidectomy or laryngeal cartilage fracture repair to restore movement or widen the airway.

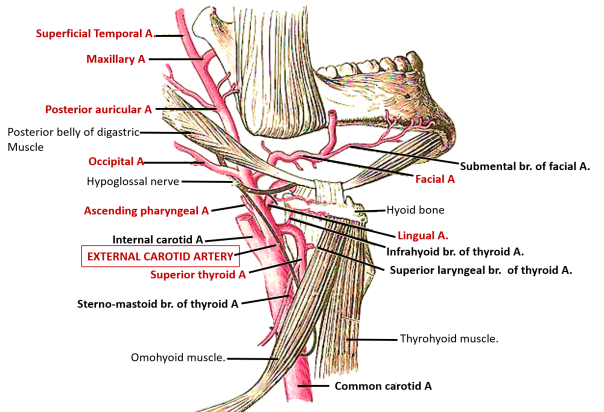

Q. External carotid artery and its branches?

The external carotid artery arises from the common carotid artery just above the bifurcation at the level of the upper border of the thyroid cartilage. It supplies blood to the neck, face and cranium.

The major branches of the external carotid artery include:

1. Superior thyroid artery: Supplies the upper thyroid lobe and infrahyoid neck muscles. It arises just below the greater cornu of the hyoid bone.

2. Lingual artery: Supplies the tongue. It arises just above the superior thyroid artery and courses medially to the tongue.

3. Facial artery: Supplies the face. It arises just above the lingual artery, loops over the inferior border of the mandible and ascends to the corner of the eye and nose.

4. Ascending pharyngeal artery: Supplies the pharynx. It is a long slender branch that ascends behind the pharynx.

5. Occipital artery: Supplies the posterior scalp. It arises posterolateral to the external carotid artery and ascends to the occiput.

6. Posterior auricular artery: Supplies the ear and posterosuperior neck. It arises just above the facial artery and ascends behind the ear.

7. Superficial temporal artery: The smaller terminal branch which supplies the lateral scalp. It arises within the parotid gland and ascends in front of the ear to the scalp.

8. Maxillary artery: The larger terminal branch which supplies the lower face, upper jaw and dura mater. It arises behind the neck of the mandible and enters the face through the mandibular notch.

The external carotid artery also gives off several smaller branches to surrounding neck muscles, parotid gland, larynx and mandible.

The major branches can be grouped according to their site of origin:

– High in the neck: Superior thyroid, lingual and facial arteries

– Middle in the neck: Ascending pharyngeal artery

– Posterosuperiorly: Occipital and posterior auricular arteries

– Terminal branches: Superficial temporal and maxillary arteries

The external carotid artery provides the main blood supply to the face, scalp, pharynx and upper aerodigestive tract. Occlusion of the external carotid artery may lead to reduced blood flow in these areas, necessitating collateral circulation from the internal carotid and vertebral arteries. The external carotid artery is also commonly used as vascular access during certain head and neck surgeries.

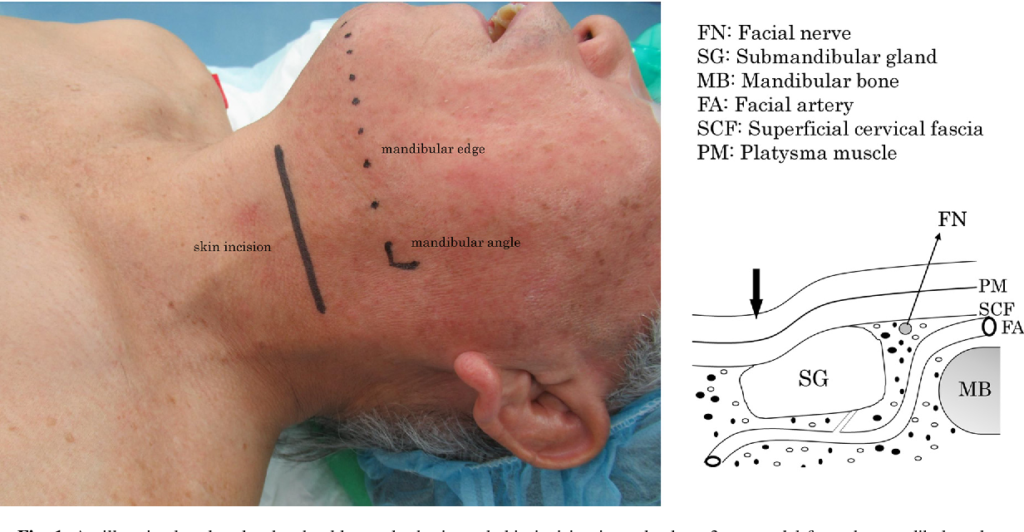

Q. nerve damage submandibular excision?

Removal of the submandibular gland (submandibulectomy) carries a risk of damage to nearby nerves. The nerves at risk include:

1. Marginal mandibular nerve: Supplies motor innervation to the muscles of lower lip depression (depressor labii inferioris). It emerges from beneath the lower border of the mandible near the midline and courses outward beneath the platysma. Damage to this nerve can cause asymmetry of the lower lip. Care must be taken when dissecting near the lower mandible during submandibulectomy.

2. Cervical branch of facial nerve: Emerges from the parotid gland and curves around the lower border of the mandible. It provides motor innervation to the muscles of facial expression in the upper neck. Injury to this branch can cause partial facial paralysis in the upper neck, with weakness of neck muscle contraction and inability to wrinkle the skin. The nerve should be identified and retracted during dissection near the angle of the mandible.

3. Lingual nerve: Provides sensation to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue and floor of mouth. It is at risk as it lies on the medial surface of the submandibular gland, closely applied to the hyoglossus muscle. Damage to the lingual nerve can cause loss of taste and sensation in the tongue and mouth, and impaired tongue mobility. Careful dissection and traction on the submandibular gland is required to visualize and protect the lingual nerve during submandibulectomy.

4. Hypoglossal nerve: Supplies motor innervation to most tongue muscles. It crosses deep to the posterior portion of the submandibular gland, so is less likely to be damaged compared to the lingual nerve. However, excessive retraction or inadvertent ligation/cautery medial to the gland could injure the hypoglossal nerve, causing ipsilateral tongue weakness and atrophy. The path of this nerve should be considered if dissection extends posterior to the submandibular gland.

5. Inferior alveolar nerve: Enters the mandibular foramen to supply sensation to the lower teeth, gingivae and chin area. Only at risk if the submandibulectomy extends posteriorly near the mandibular foramen, which would not normally be the case. Damage can lead to dental anesthesia of the lower teeth.

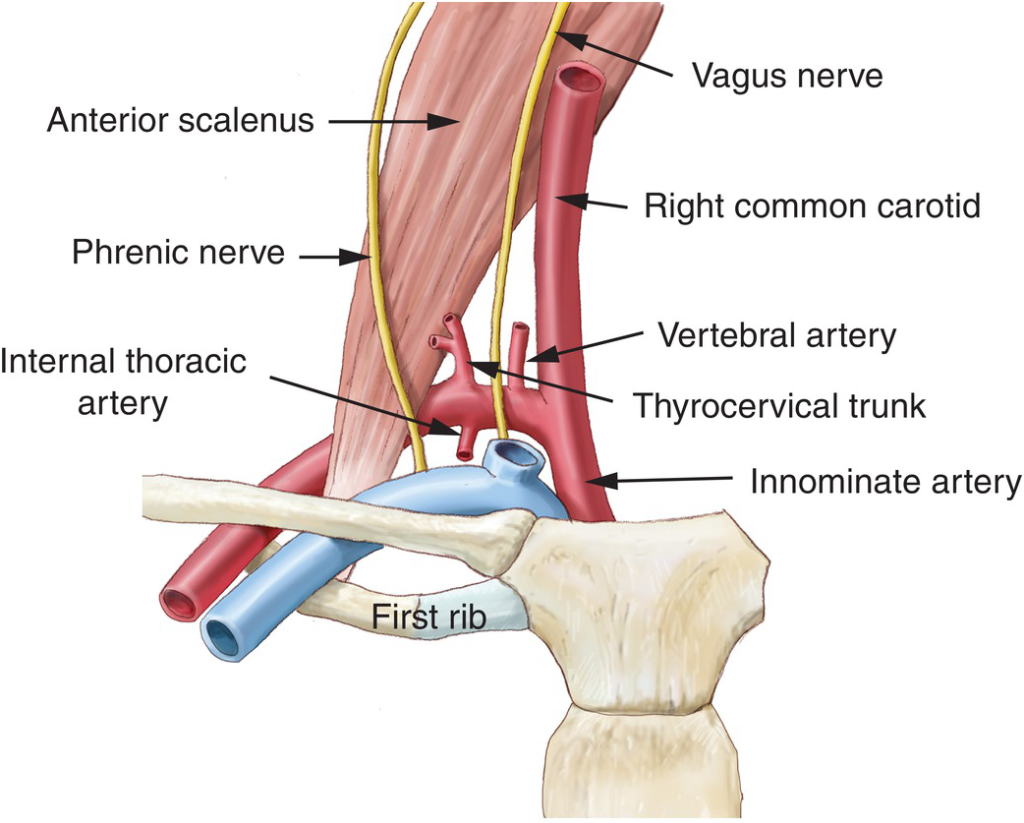

Q. Origin of subclavian vein and artery?

The subclavian vein and artery both originate from the brachiocephalic vein and trunk respectively.

Specifically:

Subclavian vein:

– Originates from the confluence of the internal jugular vein and vertebral vein at the root of the neck. This point is called the jugulovertebral venous junction.

– Descends posterior to the clavicle in the superior mediastinum before joining the internal jugular vein to form the brachiocephalic vein.

– Receives tributaries draining the shoulder, thorax and upper limb including the external jugular vein, internal thoracic vein, lateral thoracic vein and axillary vein.

– Passes anterior to the scalene muscles and first rib in the root of the neck. The phrenic nerve crosses anterior to the subclavian vein at this level.

– Drains blood from the head, neck, thorax and upper limb into the superior vena cava via the brachiocephalic veins. Occlusion of the subclavian vein causes backflow and congestion in these areas.

Subclavian artery:

– Originates from the brachiocephalic trunk behind the upper part of the manubrium. The brachiocephalic trunk bifurcates into the right common carotid and subclavian arteries.

– Arches over the first rib to descend into the axilla behind the clavicle, where it becomes the axillary artery.

– Passes behind the scalenus anterior and medius muscles in the root of the neck, with the phrenic nerve crossing in front of it.

– Supplies blood to the shoulder, thorax, spinal cord, brainstem and upper limb. Occlusion causes ischemia in these regions including vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

– Gives off three main branches: 1) Vertebral artery – ascends through foramina in cervical vertebrae to supply the posterior circulation, 2) Internal thoracic artery – descends behind the sternum, 3) Thyrocervical trunk – branches further to supply neck and shoulder.

In summary, the subclavian vein and artery originate immediately lateral to the first rib at the root of the neck, passing between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. The subclavian vein drains the head, neck and upper limb, while the subclavian artery supplies these regions as well as the thorax and vertebral circulation. Their relative anatomy at this level is important when performing procedures such as subclavian catheterization, angioplasty or fracture reduction in the neck and shoulder.

Q. Safe incision for submandibular gland ?

Safe incision for submandibulectomy (removal of submandibular gland) should avoid nearby nerves while allowing adequate exposure. The recommended incision is:

– A curved incision 2-3 cm below and parallel to the lower border of the mandible. This avoids the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve that crosses beneath the mandible.

– Extending from the lower border of the mandible at its midpoint to just anterior to the angle of the mandible. This avoids the upper cervical branch of the facial nerve curving around the mandible as well as the facial vessels.

– Raising subplatysmal flaps superiorly to the lower border of the mandible and inferiorly to the level of the hyoid bone. This lifts the platysma off nearby nerves, allowing them to be identified and protected during deeper dissection.

– Performing deeper dissection to visualize and protect the lingual nerve on the medial aspect of the gland, and hypoglossal nerve crossing posteriorly. The lingual nerve is closely applied to the gland and at highest risk of damage. Dissecting in a plane beneath the gland can protect these nerves.

– Ligating the connecting duct (Wharton’s) close to the gland to minimize damage to surrounding tissue. The lingual nerve often adheres closely to Wharton’s duct, so ligating as distally as possible reduces manipulation of this area.

– Closing the incision in layers after removal of the gland. Ensure hemostasis and that all anatomical layers are approximated accurately to minimize contour irregularity.

This incision and careful dissection technique helps maximize surgical access while reducing risks to nearby nerves (marginal mandibular, cervical facial branch, lingual, hypoglossal) and blood vessels that could be damaged during submandibulectomy. With adherence to these steps, injury to surrounding structures can be minimized for safe removal of the submandibular gland.

Key points:

1. Curved incision 2-3 cm below and parallel to mandible

2. Extends from midline to just anterior to mandibular angle

3. Raise subplatysmal flaps to access deeper area

4. Identify and protect nearby lingual, hypoglossal and facial nerves

5. Ligate Wharton’s duct distally to avoid lingual nerve damage

6. Close incision accurately in layers

Q. Origin of subclavian vein and artery?

The subclavian vein and artery both originate from the brachiocephalic vein and trunk respectively.

Specifically:

Subclavian vein:

– Originates from the confluence of the internal jugular vein and vertebral vein at the root of the neck. This point is called the jugulovertebral venous junction.

– Descends posterior to the clavicle in the superior mediastinum before joining the internal jugular vein to form the brachiocephalic vein.

– Receives tributaries draining the shoulder, thorax and upper limb including the external jugular vein, internal thoracic vein, lateral thoracic vein and axillary vein.

– Passes anterior to the scalene muscles and first rib in the root of the neck. The phrenic nerve crosses anterior to the subclavian vein at this level.

– Drains blood from the head, neck, thorax and upper limb into the superior vena cava via the brachiocephalic veins. Occlusion of the subclavian vein causes backflow and congestion in these areas.

Subclavian artery:

– Originates from the brachiocephalic trunk behind the upper part of the manubrium. The brachiocephalic trunk bifurcates into the right common carotid and subclavian arteries.

– Arches over the first rib to descend into the axilla behind the clavicle, where it becomes the axillary artery.

– Passes behind the scalenus anterior and medius muscles in the root of the neck, with the phrenic nerve crossing in front of it.

– Supplies blood to the shoulder, thorax, spinal cord, brainstem and upper limb. Occlusion causes ischemia in these regions including vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

– Gives off three main branches: 1) Vertebral artery – ascends through foramina in cervical vertebrae to supply the posterior circulation, 2) Internal thoracic artery – descends behind the sternum, 3) Thyrocervical trunk – branches further to supply neck and shoulder.

In summary, the subclavian vein and artery originate immediately lateral to the first rib at the root of the neck, passing between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. The subclavian vein drains the head, neck and upper limb, while the subclavian artery supplies these regions as well as the thorax and vertebral circulation. Their relative anatomy at this level is important when performing procedures such as subclavian catheterization, angioplasty or fracture reduction in the neck and shoulder.

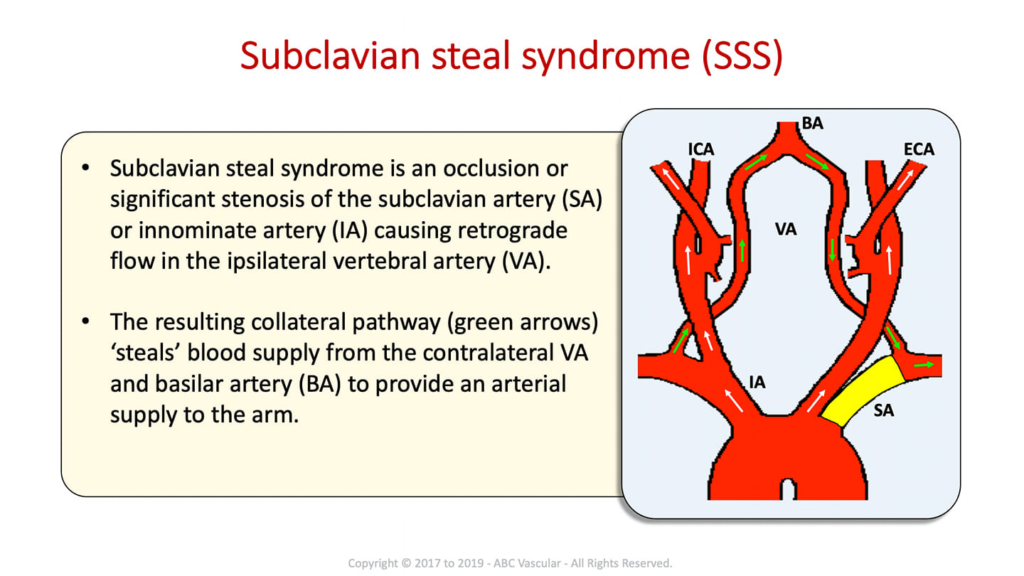

Q. Define subclavian steal syndrome?

Subclavian steal syndrome refers to a condition where blood flow is ‘stolen’ from the vertebral artery to the distal subclavian artery due to proximal subclavian stenosis or occlusion. This can lead to neurologic symptoms from vertebrobasilar insufficiency including dizziness, dysarthria, syncope and visual changes.

Details of subclavian steal syndrome:

1. It is caused by stenosis or occlusion of the proximal subclavian artery, most often due to atherosclerosis. This reduces blood flow to the arm and also reverses flow in the ipsilateral vertebral artery.

2. The vertebral artery normally supplies the posterior circulation of the brain including the cerebellum, brainstem, occipital lobes and inner ear. Reverse flow in the artery ‘steals’ blood away from these structures.

3. Symptoms occur on exertion or extending the arm since increased arm blood flow demand worsens the flow reversal in the vertebral artery. Lying down or lowering the arm can relieve symptoms.

4. Physical exam may detect reduced or absent pulses in the affected arm, BP difference in both arms, and an audible bruit over the subclavian artery. Neurologic signs include limb ataxia, dysarthria, nystagmus and visual field defects.

5. Diagnosis is by CT angiography, MR angiography or duplex ultrasound. This confirms subclavian stenosis and detects reversed vertebral artery flow. An arteriogram may also be required before intervention.

6. Treatment options include endovascular stenting of the subclavian stenosis to improve forward flow, carotid-subclavian bypass surgery or vertebral artery revascularization procedures to restore normal vertebral circulation.

7. Lifestyle modifications include avoiding extremes of arm exertion, keeping BP well controlled and stopping smoking to prevent disease progression. Antiplatelet therapy may be commenced if not surgically managed.

Subclavian steal syndrome is a treatable cause of posterior circulation ischemia. Awareness of its clinical features aids prompt diagnosis and referral to specialists for further management. Surgery or stenting achieves good outcomes with resolution of symptoms and restoration of normal vertebrobasilar circulation in most cases.

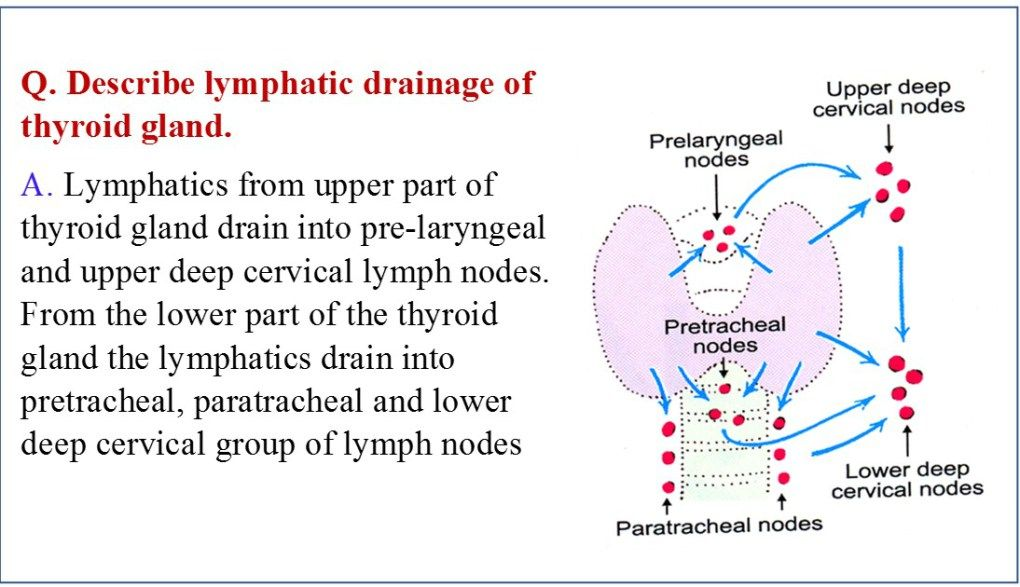

Q. Lymphatic drainage of thyroid?

The thyroid gland has an extensive lymphatic drainage. Knowledge of the lymphatic pathways is important for identification of lymph node spread in thyroid malignancies.

The lymphatic drainage of the thyroid gland is:

1. Superior thyroid nodes: Located at the superior poles of the thyroid lobes. They lie along the superior thyroid veins and drain the upper parts of the thyroid gland.

2. Middle thyroid nodes: Lie along the middle thyroid veins, draining the middle parts of the thyroid lobes. They are the most frequently involved site of nodal spread in papillary thyroid carcinoma.

3. Inferior thyroid nodes: Located at the lower poles of the thyroid, draining the inferior parts of the lobes. They lie along the inferior thyroid veins.

4. Pretracheal nodes: Lie along the recurrent laryngeal nerves and trachea. They drain the isthmus and posterolateral parts of both lobes. Also commonly involved in thyroid cancer spread.

5. Paratracheal nodes: Located in the paratracheal space adjacent to both sides of the trachea. They drain most of both thyroid lobes and isthmus. represent the primary site of nodal metastases after middle thyroid nodes.

6. Lateral neck nodes: Comprise the internal jugular nodes along the internal jugular vein, and posterior triangle nodes posterior to SCM. Metastases to these nodes tend to occur later via lymphatic permeation. Indicates more advanced disease.

7. Mediastinal nodes: Thoracic inlet nodes located at thoracic outlet, anterior mediastinal nodes along proximal trachea and brachiocephalic nodes at tracheal bifurcation. Involvement of these distal nodes suggests lymphatic spread across normal lymph node basins. Prognosis is generally poor.

The pattern of nodal spread is usually stepwise, to adjacent nodes then progressing down the lymphatic chain to more distant nodes. Lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel node biopsy helps map lymphatic drainage in individual patients to guide the extent of nodal dissection required. Routine removal of mediastinal nodes is not recommended unless there is proven involvement.

Q. parathyroid development and relation to thyroid?

1. Origin: The parathyroid glands develop from the endoderm of the third and fourth pharyngeal pouches. The superior parathyroids arise from the fourth pharyngeal pouch, while the inferior parathyroids arise from the third pharyngeal pouch.

2. Migration: The parathyroid buds separate from the pharynx and migrate inferiorly along with the developing thyroid gland. The superior parathyroids descend further and eventually come to lie adjacent to the upper thyroid lobes. The inferior parathyroids migrate a shorter distance to lie near the lower thyroid poles.

3. Blood supply: The parathyroid glands derive their blood supply from adjacent thyroid arteries. The superior parathyroids are supplied by the superior thyroid arteries, while the inferior parathyroids receive blood from the inferior thyroid arteries. This shared blood supply means that damage to the thyroid vasculature during surgery risks devascularizing the parathyroid glands.

4. Nerve supply: Parathyroid glands receive sympathetic innervation from the same network of nerves that supply the thyroid, i.e. superior, middle and inferior cervical ganglia. Damage to these sympathetic pathways can temporarily impair parathyroid function. Parathyroids themselves lack sensory innervation.

5. Attachment to thyroid: The parathyroid glands come to lie adjacent to the thyroid but remain separate glands. They are attached to the posterior thyroid capsule, but do not fuse with thyroid tissue. The close proximity means parathyroids can be incidentally excised, damaged or devascularized during thyroid surgery if not properly identified and preserved.

The parathyroid glands come to rest on the posterior capsule of the thyroid gland. They are attached to and ensheathed by the posterior thyroid capsule, but their secretory epithelial cells remain separated from thyroid follicular cells.

6. Thyroid hormone effects: Thyroid hormone has inhibitory effects on parathyroid function and gland development. Neonatal hypothyroidism leads to parathyroid hyperplasia due to lack of this inhibitory regulation. Treatment with levothyroxine normalizes parathyroid growth and secretory activity.

Q. Surface anatomy of thyroid gland?

The thyroid gland is a butterfly-shaped organ located in the neck. Here are the key surface anatomy features of the thyroid gland:

1. Location: It lies against the lower part of the larynx and upper trachea. The thyroid cartilage and cricoid cartilage lie just above the upper poles of the thyroid gland.

2. Shape: The thyroid gland has two lobes connected by an isthmus. The right and left lobes on either side appear rounded, while the isthmus crossing the midline is narrower. The gland may appear larger in women, during pregnancy or in Graves’ disease.

3. Borders:

– Superior border – Felt as a ridge below the thyroid cartilage, more prominent when swallowing.

– Inferior border – Extends down to the level of the 5th or 6th tracheal ring.

– Side borders – Lie adjacent to the carotid sheaths containing the common carotid arteries, internal jugular veins and vagus nerves. The borders feel rounded and smooth.

4. Size: A normal gland is about 2 inches in length, 1.5 inches wide and 0.3 inches thick, in women. It is slightly smaller in men. Difficult to determine exact size through palpation alone.

5. Consistency: The thyroid gland feels firm, rubbery in texture and evenly tapered. Any hard lumps or nodules felt within the gland may require further investigation as it can indicate thyroid cancer or nodules.

6. Mobility: The thyroid glides freely on underlying tissues during swallowing. It rises slightly at the level of the larynx before descending back down. Lack of mobility may indicate thyroid inflammation or malignancy.

7. Other features: Tracheal tug is a downward pull felt while swallowing due to the thyroid gland moving against the trachea. This feature is often more noticeable in goiter or hypothyroidism. The carotid pulse may also be felt lateral to the gland.

Q. Thyroid surgery complications early and late?

Thyroid surgery, like any major procedure, carries risks of both early and late complications:

Early complications (within 30 days of surgery):

1. Recurrent laryngeal nerve damage: Causing hoarseness, dysphagia or airway obstruction. Usually transient but can be permanent. Bilateral damage is a surgical emergency.

2. Superior laryngeal nerve damage: Causing weak, hoarse voice and altered laryngeal sensation. Often recover over weeks to months.

3. Hemorrhage: Mild bleeding is common but severe, life-threatening hemorrhage can occur, especially if surgery was technically difficult. May require emergency surgery to control.

4. Wound infection: Especially if drains, tracheostomy or large dead space. Presents with pain, swelling, dehiscence or pus discharge. Requires antibiotics and possibly drainage.

5. Hypocalcemia: Due to hypoparathyroidism from damage or devascularization of parathyroid glands. Causes tingling, muscle spasms, seizures or arrhythmia. Usually transient but may need calcium/Vit D replacement.

6. Hypoparathyroidism: Inability to maintain calcium homeostasis long-term due to loss of or damage to parathyroid glands. Requires life-long medical therapy.

7. Tracheomalacia: Softening or collapse of trachea due to loss of thyroid gland support. Causes cough, stridor or respiratory distress. Rare and often only temporary. tracheostomy may be required.

8. Seroma: Fluid collection within dead space of surgery site. Usually resorbs spontaneously but may become infected or require drainage if persistent or symptomatic.

Late complications:

1. Hypothyroidism: Inadequate thyroid hormone due to decreased functional tissue from surgery. Requires daily levothyroxine replacement.

2. Hyperthyroidism: If too much thyroid tissue remains, causing Graves’ like symptoms. May need anti-thyroid drugs or radioactive iodine therapy.

3. Hypertrophic/keloid scarring: Thickened, raised scar that can become cosmetically displeasing. More common in younger individuals with darker skin types. Steroid injections or excision may improve appearance.

4. Chyle leak: From thoracic duct injury. Causes neck swelling, fluid collection and nutritional deficiency. Usually managed conservatively but may require lymphangiography and embolization.

5. Adhesions: Causing difficulty swallowing, choking, neck discomfort or limited mobility. May require repeat surgery to lyse adhesions in severe cases.

Q. Identify the structures?

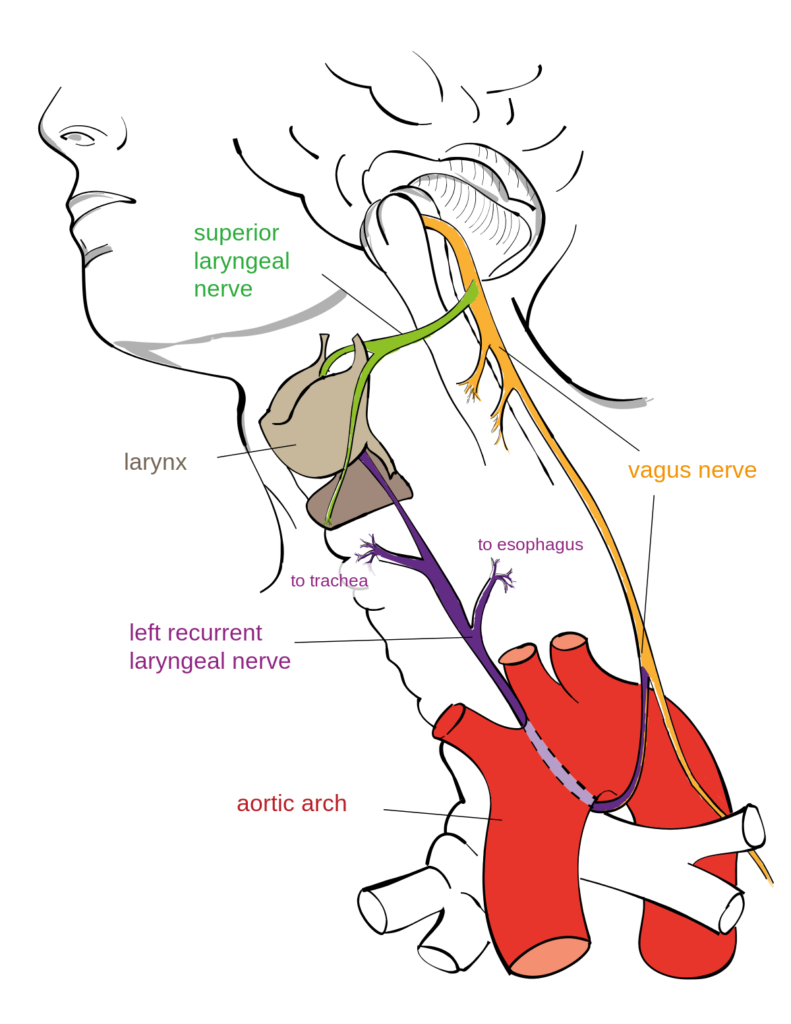

Q.Nerves that can get damaged on thyroid surgery?

The major nerves at risk of damage during thyroid surgery are:

1. Recurrent laryngeal nerve: Provides motor innervation to all intrinsic laryngeal muscles except cricothyroid. Damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve during thyroid surgery can cause:

– Hoarseness: Due to vocal cord paralysis and impaired phonation. Often temporary but can be permanent.

– Dysphagia: Difficulty swallowing from lack of vocal cord adduction. Usually mild but can lead to aspiration in severe cases.

– Airway obstruction: Bilateral damage causes bilateral vocal cord paralysis and risk of airway compromise. Tracheostomy may be required.

The risk of damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve can be minimized by:

– Careful identification of the nerve during dissection near the tracheoesophageal groove.

– Ligation and division of thyroid vasculature away from the nerve.

– Avoidance of excessive traction or use of diathermy near the nerve.

– Intraoperative nerve monitoring using endotracheal tube electrodes during high-risk surgery.

2. Superior laryngeal nerve: Provides sensation above the vocal folds and motor supply to cricothyroid. Damage causes:

– Altered/reduced sensation in the supraglottic larynx. Usually well tolerated with few symptoms.

– Weak, hoarse voice from impaired cricothyroid function. Voice fatigue may occur with prolonged use.

The external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve is at highest risk, often traversing the superior thyroid pedicle. Careful dissection and ligation away from the nerve can help prevent damage.

3. Sympathetic nerves: Follow the superior and inferior thyroid arteries. Damage causes unilateral ptosis, miosis and facial flushing (Claude Bernard Horner syndrome) due to interrupted sympathetic supply. Usually a temporary and minor complication.

Q.what is the relation of parathyroid with pretracheal fascia?

1. The pretracheal fascia is a thin layer of connective tissue that covers the trachea and surrounds the thyroid gland. It provides an anatomical barrier separating the thyroid and airway anteriorly from the esophagus posteriorly.

2. The superior parathyroid glands develop from the fourth pharyngeal pouch and descend to lie on the posterior surface of the upper thyroid lobes, surrounded by the pretracheal fascia. They remain embedded within this fascial layer, covered on both anterior and posterior surfaces.

3. The inferior parathyroid glands develop from the third pharyngeal pouch and usually come to rest next to the lower thyroid poles, also enveloped within the pretracheal fascia. However, the inferior glands have a more variable position and are sometimes found within the thymus gland or posterior to the esophagus, still covered by fascial layers.

4. The close association with the pretracheal fascia means that the parathyroid glands can be difficult to identify during thyroid surgery. They often appear as indistinct round or oval masses embedded within or adherent to the fascia. Careful dissection is required to mobilize and preserve the glands, or determine if they have been excised.

5. Damage to or removal of the pretracheal fascia puts the parathyroid glands at risk during thyroidectomy. If the fascial layer is disrupted or incised, the glands may retract making them harder to locate and preserve. It also increases the chance of devascularizing the glands by damaging small arteries that pierce the fascia to supply the parathyroids.

6. In some cases, parathyroid glands may be intentionally autotransplanted by excising them together with the surrounding fascia and inserting the block of tissue into a muscle pocket. This technique is used when preservation of the glands in situ is not possible, to maintain parathyroid function.

Q.accessory nerve, what does it supply, what happens when it is paralyzed, how to test these muscles ?

1. The accessory nerve supplies the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and trapezius muscles. It provides essential motor innervation for head/neck movement and shoulder function.

2. Damage to the accessory nerve results in:

– Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) palsy: Impaired head/neck flexion, rotation and lateral flexion away from the affected side. The head is pulled towards the paralyzed side by unopposed antagonists. Test by asking the patient to flex, rotate and tilt their head against resistance.

– Trapezius palsy: Difficulty elevating, retracting and depressing the scapulae. Impaired ability to abduct and extend the arms overhead. Test by asking the patient to shrug their shoulders, and abduct/extend their arms against resistance. Observe for scapular winging, drooping and asymmetry.

3. When the accessory nerve is paralyzed, patients experience:

– Neck weakness interfering with contralateral head/neck flexion and rotation. The head is pulled to the affected side.

– Impaired shoulder abduction and difficulty raising arms above the head. ‘Shrugging’ ability is lost.

– Prominent scapular protrusion and drooping. The scapulae appear ‘winged’ when arms are abducted.

4. Accessory nerve palsy is often unilateral and caused by:

– Surgical damage (e.g. radical neck dissection, lymph node biopsy)

– Trauma/stretching of the nerve (e.g. whiplash injury, compression)

– Severe cases may require nerve grafting. Milder injuries can recover over weeks-months with physical therapy and scapular bracing.

5. Clinical diagnosis is made through evaluation of SCM/trapezius strength– – Test by asking the patient to shrug shoulders, abduct arms overhead or push hands against a wall. Observe for winging of the scapulae, drooping of the shoulder or weakness. Needle EMG helps confirm loss of motor innervation.

Q. difference in origin of right and left RLNs?

1. The right RLN branches from the right vagus nerve at the root of the neck and loops under the right subclavian artery before turning upwards. This path under the subclavian artery puts the right RLN at greater risk of damage during thyroidectomy and other surgeries of the right neck.

2. The left RLN branches from the left vagus nerve beneath the aortic arch before ascending in the neck. Despite its shorter course, the left RLN is also at risk during mediastinal surgeries, thoracic aneurysm repair and some thyroidectomies.

3. Due to its longer, more oblique course under the subclavian artery, damage to the right RLN often results in delayed vocal cord paralysis. As the nerve is stretched but not immediately transected, vocal cord function may be initially spared but deteriorate over 24-72 hours. Left RLN injury typically causes immediate paralysis due to its more direct course.

4. The incidence of transient vocal cord paresis is higher with right RLN injuries (15-30%) compared to the left side (3-8%). Transection or permanent damage also tends to be more common on the right. Recovery depends on whether the nerve can remain in continuity or requires grafting/regeneration.

5. Right RLN injury is more often associated with hoarseness, particularly when shouting or singing at high intensity. Left RLN damage typically causes breathiness, low volume and inability to project the voice. Bilateral paresis results in the most severe and complex voice impairment, requiring urgent medialization procedures.

6. With unilateral damage, the contralateral normal RLN prevents life-threatening airway obstruction by abducting the unopposed vocal cord. Bilateral injuries place the patient at risk of glottic closure and require emergency tracheostomy.

Q.Why do inferior parathryoids go down into thymus?

There are a few reasons why inferior parathyroid glands may descend into or behind the thymus gland:

1. Shared embryological origin: The inferior parathyroid glands and thymus both develop from the third pharyngeal pouch. During early development, the inferior parathyroid buds remain closely associated with the thymus primordium before separating to ascend towards the developing thyroid gland. In some cases, this separation may be incomplete, resulting in parathyroid tissue that remains within or behind the thymus.

2. Variable migration: The inferior parathyroid glands have a more variable migration pattern during development compared to the superior glands. While the superior parathyroids typically descend a short distance to lie near the upper thyroid poles, the inferior glands can descend a more variable distance before reaching their final position. Occasionally, their migration may halt behind or within the thymus instead of continuing to the lower thyroid poles.

Q. What physiological problems after total thyroidectomy (hypothyroidism and hypoparathyroidism?

Total thyroidectomy, removal of the entire thyroid gland, results in two major physiological problems:

1. Hypothyroidism: With complete removal of thyroid tissue, there is no residual functioning gland to produce thyroid hormones (T3 and T4). This results in hypothyroidism with symptoms of:

– Fatigue and low energy

– Increased sensitivity to cold

– Weight gain

– Depression or mood changes

– Muscle aches, cramps or weakness

– Constipation

– Dry skin and hair

– Impaired concentration or memory

Treatment requires daily administration of levothyroxine (T4) hormone medication to replace natural production and correct the hormone deficiency. Careful monitoring and adjustment of dosage is needed to optimize treatment.

2. Hypoparathyroidism: The parathyroid glands are intimately associated with the thyroid gland, so are at risk of damage or accidental removal during total thyroidectomy. Loss of parathyroid function results in hypoparathyroidism with symptoms of:

– Hypocalcemia: Low blood calcium levels which can cause tingling fingers, muscle spasms or cramps, abdominal pain, anxiety, and seizures in severe cases.

– Hyperphosphatemia: High blood phosphate due to reduced calcium excretion in urine. Usually does not cause symptoms but may indicate the underlying problem.

– Low or undetectable parathyroid hormone levels.

Treatment involves high dose calcium and vitamin D supplementation to increase blood calcium levels in the absence of parathyroid hormone. Care needs to be taken to avoid over-supplementation and hypercalcemia. Some cases may require parathyroid autotransplantation to restore gland function.

Other issues following total thyroidectomy include:

– Difficulty swallowing or hoarseness due to damage of laryngeal nerves. Typically temporary but may be permanent.

– Hypertrophic or keloid scarring which can be cosmetically displeasing. More common in younger individuals.

– Adhesions causing neck discomfort, choking sensation or limited mobility. May require lysis to relieve symptoms.

Q. what does PTH do ?

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is secreted by the parathyroid glands. It plays a crucial role in regulating blood calcium levels and bone metabolism:

1. PTH increases blood calcium levels by:

– Releasing calcium from bone: PTH stimulates osteoclasts to break down bone and release calcium into the bloodstream. This is known as bone resorption.

– Increasing calcium absorption in the kidneys: PTH causes the kidneys to retain more calcium that would otherwise be excreted in urine. It also activates vitamin D which promotes intestinal calcium absorption.

– Increasing calcium reabsorption in the kidneys: The kidneys filter large amounts of calcium, but normally excrete over 99% of the filtered load. PTH stimulates calcium reabsorption so more is conserved.

– Mobilizing calcium from the intestines: PTH indirectly activates vitamin D which enhances the absorption of dietary calcium in the intestines so less is lost in stool.

2. PTH decreases blood phosphate levels by:

– Increasing phosphate excretion in urine: PTH causes more phosphate to be filtered and excreted in urine rather than reabsorbed in the kidneys. This lowers overall blood phosphate levels.

– Decreasing intestinal phosphate absorption: Elevated PTH indirectly inhibits the absorption of phosphate from foods in the intestines. Less is taken up into the bloodstream so blood levels fall.

3. PTH regulates bone turnover by activating both osteoclasts to resorb bone, and osteoblasts which form new bone. This constant activation and balance between bone resorption and formation helps reshape and strengthen the skeleton. Excessive or unregulated PTH secretion leads to conditions like osteoporosis.

4. PTH secretion is normally tightly regulated based on blood calcium levels. When calcium levels rise, less PTH is released. When blood calcium decreases, more PTH is secreted to restore balance until normal levels are achieved again. This negative feedback loop helps maintain calcium homeostasis.

The common carotid artery bifurcates into the internal and external carotid arteries at the level of the superior border of the thyroid cartilage in the neck. This corresponds to the level of the 4th cervical vertebra, also called C4.

The key points about the carotid bifurcation are:

1. It is a landmark during neck surgeries to locate structures like the recurrent laryngeal nerve, superior thyroid artery, etc. The nerve and artery ascend close to the common carotid, so the bifurcation indicates their approximate level.

2. It usually occurs at the upper border of the thyroid cartilage, which is at the same level as the disks between the 3rd and 4th cervical vertebrae or C3-4 level. This can be located by palpating the prominence of the thyroid cartilage during neck extension.

3. The internal carotid artery arises from the bifurcation and has no branches in the neck. It ascends vertically in the carotid sheath posterior to the external carotid artery. The external carotid gives multiple branches that supply the face, scalp, neck and meninges.

4. The superior thyroid artery usually arises at or just below the level of bifurcation. It supplies the thyroid gland and infrahyoid muscles. The lingual and facial arteries originate from the external carotid artery just above the bifurcation.

5. The carotid sinus baroreceptor reflex mechanism is located at the origin of the internal carotid artery. The carotid sinus contains specialized baroreceptors that sense mean arterial pressure. Carotid sinus massage at the bifurcation can stimulate these baroreceptors resulting in bradycardia and fall in blood pressure.

6. Atherosclerotic plaques tend to form at or just below the carotid bifurcation, causing carotid artery stenosis. This is because the velocity of flow changes and turbulence develops at the bifurcation, damaging the arterial endothelium. Significant stenosis warrants treatment like carotid endarterectomy to prevent stroke.

7. The nodose ganglion of the vagus nerve lies just below the carotid bifurcation, between the internal jugular vein and internal carotid artery. The root of the vagus nerve is behind the ganglion and sheath.

8. Lymph nodes located at the level of bifurcation include the peribifurcation, superior thyroid, and jugulodigastric nodes which can be sites of metastasis in head and neck cancers.

To summarize, the carotid bifurcation is an important surgical landmark in the neck located at C3-4 level. Multiple neurovascular structures converge here, so a thorough knowledge of the anatomy and its variations is essential for safe surgery in this region.

Hoarseness of voice often occurs in bronchial carcinoma due to injury of the recurrent laryngeal nerves. The reasons for this are:

1. The recurrent laryngeal nerves ascend in the tracheoesophageal groove very close to the posterior wall of the bronchi. Bronchogenic carcinoma arising from the bronchi can directly infiltrate, compress or invade the recurrent laryngeal nerves. This causes vocal cord paralysis and hoarseness of voice which may be the first presenting symptom of lung cancer.

2. The recurrent laryngeal nerves are also close to the tracheobronchial lymph nodes. Enlarged cancerous lymph nodes can compress the nerves leading to hoarseness. Metastasis to the lymph nodes indicates advanced disease.

3. Tumor spread to the azygous vein or esophagus can also damage the recurrent laryngeal nerves during their retroesophageal course, resulting in vocal cord palsy. This usually occurs later in the disease process.

4. Tumors of the lung apex or superior sulcus (Pancoast tumor) can invade the brachial plexus and stellate ganglion in the thoracic inlet. Damage to the sympathetic nerves causes Horner’s syndrome and damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerves within the plexus leads to hoarseness of voice.

5. Secondary erosion of adjacent vertebral bodies by the tumor can compress or infiltrate the recurrent laryngeal nerves as they ascend in the neck, before entering the chest. This can also occur from subsequent vertebral metastasis.

6. Lymphadenopathy at the lung root or paratracheal nodes secondary to the bronchogenic carcinoma can distort or obstruct the subclavian arteries. The recurrent laryngeal nerves loop around these arteries, so distortion or occlusion compromises the blood supply to the nerves leading to their dysfunction.

In summary, hoarseness of voice in bronchogenic carcinoma most often results from direct damage to one or both recurrent laryngeal nerves from tumor infiltration, compression by enlarged lymph nodes, secondary invasion of surrounding structures like esophagus or vertebrae or compromised vascular supply. Treatment may include radiation therapy for symptomatic relief, chemotherapy, resection of primary tumor or lymph nodes, or surgical decompression of the recurrent laryngeal nerves. Prognosis depends on the stage at which hoarseness develops and degree of nerve injury.

When the facial artery is injured or ligated, collateral circulation develops gradually to maintain blood supply to the facial tissues. The main collateral pathways include:

1. Opposite facial artery: The contralateral facial artery provides collateral supply to the midface by anastomosing with septal and nasal branches of the injured artery. This helps minimize ischemia to the nose, upper lip and mid cheeks.

2. Superficial temporal artery: It anastomoses with the transverse facial artery and other branches of the external carotid system to provide collateral flow to the lower face, chin and lateral cheeks. Communication between the frontal and supraorbital arteries also help supply the forehead and anterior scalp.

3. Internal carotid system: The distal branches of the internal carotid artery like ophthalmic, infraorbital and dorsal nasal arteries anastomose with branches of external carotid to supply the medial canthus, root of nose, upper lip and dorsum of nose. The ophthalmic artery also provides collateral flow to the occipital artery to supply the posterior scalp.

4. Vertebral artery: The occipital artery which arises from the vertebral system sends collateral branches to supply the posterior scalp, auricle and posterosuperior aspect of the cheek. This minimizes ischemia to the scalp and external ear following facial artery ligation.

5. Submental and submandibular arteries: They collateralize with the inferior labial and mandibular branches of the facial artery to provide blood flow to the chin, lower lip and angle of the mouth.

6. Posterior auricular artery: It supplies the posterosuperior ear, posterior scalp and angle of the mandible. Septal branches from the external carotid communicate with nasal branches of the facial artery.

7. Intramuscular anastomoses: Within the cheek muscles like buccinator and risorius, there are arteriole-venule shunts that maintain circulation even with loss of major arterial supply. This prevents muscle necrosis until collaterals develop.

To summarize, following facial artery injury, a rich network of collateral vessels develop from the contralateral facial artery, internal and external carotid systems as well as vertebral artery to restore circulation to the face. Intramuscular anastomoses also provide interim blood flow until major collaterals are established. This explains why permanent damage is rare in most cases of facial artery ligation provided there is no associated trauma or infection. Adequate hydration, head elevation and monitoring are recommended during this period.

The nerve lateral to the trachea is the recurrent laryngeal nerve. It is a branch of the vagus nerve that provides motor innervation to the larynx and sensory input to the laryngopharynx.

Key points about the recurrent laryngeal nerve:

• It arises from the vagus nerve in the root of the neck. The right recurrent laryngeal nerve loops around the right subclavian artery while the left nerve loops under the aortic arch. This is of clinical importance during thyroid or cardiac surgeries.

• It ascends in the tracheoesophageal groove, close to the lateral wall of the trachea. The esophagus separates it from the pleura and lungs.

• It provides motor innervation to all the intrinsic muscles of the larynx except cricothyroid. This includes the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle which is responsible for abducting the vocal cords. Damage to the nerve can cause vocal cord paralysis.

• It supplies sensory innervation to the mucosa of the laryngopharynx, piriform recess and vocal folds. Damage leads to loss of sensation in these areas.

• It is susceptible to damage or compression by thyroid disease, tumors in the root of the neck or aortic aneurysms. This can lead to hoarseness of voice or difficulty breathing.

• The left recurrent laryngeal nerve is more prone to damage during surgery due to its longer course under the aortic arch. Surgeons need to meticulously identify the nerve during thyroidectomies or anterior neck surgeries to prevent inadvertent damage.

• Bilateral damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve can cause acute respiratory obstruction due to vocal cord paralysis and requires an emergency tracheostomy.

• The recurrent laryngeal nerve is identified on CT/MRI as a small round structure lateral to the trachea, separated from it by a fat plane. It can be traced back proximally to the vagus nerve and subclavian or aortic arch.

In summary, the recurrent laryngeal nerve provides motor and sensory supply to the larynx. Its proximity to the trachea and long retroesophageal course makes it susceptible to damage, leading to dysfunction of the vocal cords and larynx. Care must be taken to identify and preserve it during neck surgeries.

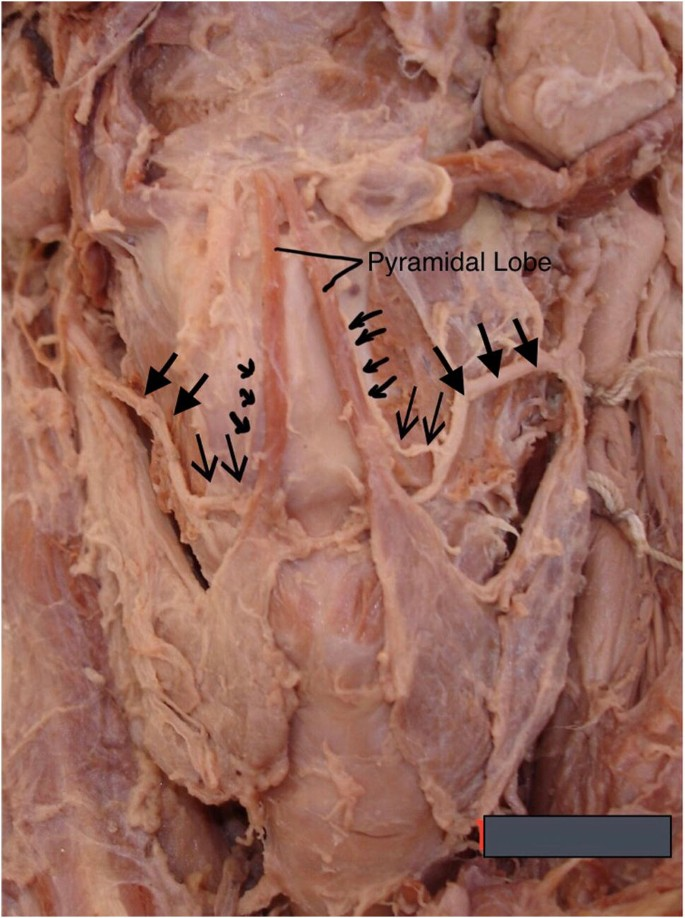

The pyramidal lobe of the thyroid gland is a small projection of thyroid tissue extending upwards from the upper pole of either lobe of the thyroid gland. It is present in about 50% of people. It may contain functional thyroid tissue and is important during thyroid surgeries to avoid leaving behind remnant tissue.

Key points about the pyramidal lobe:

• It is made of normal thyroid tissue and may contain thyroid follicles.

• It arises from the upper pole of either thyroid lobe, usually the left lobe.

• It has a pyramidal or conical shape and projects upward in the midline.

• It is a vestige of the thyroglossal duct during embryonic development. The thyroglossal duct normally disappears but remnants may persist as the pyramidal lobe.

• It is present in about 50% of the population according to autopsy studies. The incidence varies in different ethnic groups and maybe slightly higher in women.