Giant Cell Arteritis

Stem: 60 F, temporal pain/ skull tenderness on mastication , transient vision loss.

Q. What is GCA?

• Pathology: GCA involves a granulomatous arteritis, primarily affecting large and medium arteries. The inflammation destroys the elastic lamina and thickens the intima of arteries. Multinucleated giant cells are present, along with macrophages, dendritic cells, CD4+ T cells, B cells and cytokines like IL-6, IL-17 and IL-21.

• Epidemiology: Incidence of 18-30/100,000 in those over 50 years. Higher risk in Scandinavian and Northern European populations. Women affected twice as often, suggesting possible hormonal influences. Genetics also contribute, with higher concordance in identical twins.

• Clinical features:

– Headaches (usually temporal area), scalp tenderness. Worsen with jaw movement/chewing.

– Visual symptoms (diplopia, amaurosis fugax, acute vision loss). Due to occlusion of ophthalmic or central retinal arteries.

– Claudication of jaw muscles or tongue. Pain while talking or swallowing.

– Systemic symptoms like fever, anorexia, weight loss.

– PMR in ~50% with shoulder/pelvic girdle pain and stiffness.

• Diagnosis:

– ESR >50 mm/hr; CRP >3.0 mg/L. Normochromic, normocytic anemia. Platelet count may be elevated. LFT(ALP) also

– Temporal artery biopsy showing transmural granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells. Halo or compression sign on ultrasound.

– MRI/MRA or CTA may show artery wall thickening or stenosis but biopsy remains gold standard.

• Treatment: High dose glucocorticoids (40-60 mg prednisone daily) to induce remission and prevent vision loss. Then slow taper over months to 2-5 mg/day maintenance. Relapse common, may require long term low dose steroids. Immunosuppressants used in refractory cases.

• Prognosis: With treatment, 70% recover vision and 75-90% 5-year survival. Relapses occur in 30-50% of patients, usually within 2 years of diagnosis. Major causes of death are cardiovascular or malignancy related to long term steroid use.

Most serious complication is occlusion of the ophthalmic artery(ICA)

• Follow up: ESR/CRP 1-2 months after diagnosis and with each taper. Annual PPD. Bone density screening. Ophthalmology review for any visual symptoms. Temporal artery biopsy site checked. Cardiovascular risk factors monitored and managed.

Q. Which part of vessel is affected most ?

In Giant Cell Arteritis, the tunica media layer of arteries is primarily affected. Key points:

• The tunica media normally contains smooth muscle cells, elastic fibers and connective tissue. It provides elasticity and contractility to arteries.

• In GCA, the elastic laminae in the tunica media become fragmented. This results in a loss of elasticity and weakening of the arterial wall.

• A granulomatous inflammation develops in the tunica media, consisting of:

– Multinucleated giant cells: Formed by fusion of macrophages, contain multiple nuclei. Give GCA its name.

– Macrophages: Release inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 that drive inflammation.

– CD4+ T cells: Predominant lymphocyte, activated by macrophages. Release cytokines (IL-17, IL-21) that recruit other inflammatory cells.

– Dendritic cells: Present arterial wall antigens to T cells, activating them.

– B cells: Produce autoantibodies against arterial wall antigens that may contribute to inflammation.

• This inflammatory infiltrate expands into the intima, causing intimal hyperplasia (thickening) which can occlude the vessel lumen.

• Temporal artery biopsy shows this granulomatous panarteritis most prominently in the tunica media. The internal elastic lamina becomes fragmented, and the media is replaced by inflammatory cells. The intima also becomes thickened.

• While the temporal artery is commonly biopsied, GCA can affect all arteries of the head and neck, as well as the aorta and its major branches. Any medium to large artery may be involved.

• With treatment, inflammation subsides but damaged arteries remain weakened. This contributes to the risk of aneurysm formation or rupture even after inflammation resolves.

So in summary, the hallmark histopathology of GCA involves destruction of the tunica media, including fragmentation of elastic laminae, and development of an inflammatory panarteritis. The temporal artery is a convenient site to diagnose this via biopsy, but GCA represents a systemic arteritis that can affect all large and medium arteries. Treatment focuses on controlling this inflammation to limit damage, but arteries remain permanently affected.

Q. One simple blood test to prove ?

An elevated Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) is useful in supporting a diagnosis of Giant Cell Arteritis. Key points:

• The ESR is a simple blood test that measures the rate at which red blood cells settle in a test tube. It is a non-specific marker of inflammation.

• In GCA, the ESR is almost always markedly elevated, typically >50 mm/hour. Very high ESRs >100 mm/hour are common.

• An elevated ESR alone does not confirm the diagnosis, as any cause of inflammation can raise the ESR. However, a normal ESR makes the diagnosis of GCA very unlikely.

• The ESR rises due to increased plasma fibrinogen and immunoglobulins in inflammation. These cause the red cells to stack and settle more rapidly.

• The ESR correlates with disease activity in GCA. It falls with treatment as inflammation is controlled by steroids. It may rise again if inflammation returns during steroid taper.

• Monitoring the ESR during follow up helps determine if steroids can be reduced or if the dose needs to remain stable or increased. A rise in ESR signals the need to slow or postpone a planned taper.

• Other markers that are often elevated in GCA include C-reactive protein (CRP), platelet count, and anemia of inflammation. These also fall with successful treatment.

• Temporal artery biopsy remains the gold standard for definitively diagnosing GCA. Elevated inflammatory markers like ESR and CRP support the diagnosis and are used to monitor disease activity and response to treatment.

• Normalization of the ESR and CRP, in addition to symptom improvement, indicates that remission has very likely been achieved, allowing more rapid tapering of steroids.

So in summary, the ESR is typically markedly elevated in GCA and is a useful initial test in suspected cases. An elevated ESR alone does not confirm the diagnosis but a normal ESR makes GCA very unlikely. The ESR is monitored along with CRP to help determine disease activity, response to steroids, and pace of steroid taper. An elevated ESR should prompt more rapid diagnosis and treatment to prevent vision loss and other complications in cases where symptoms and pathology strongly suggest GCA.

Q. Mechanism by which corticosteroids cause osteoprosis?

Corticosteroids like prednisone cause osteoporosis through several mechanisms:

1. Direct inhibition of osteoblast formation and activity: Osteoblasts are cells that build new bone. Steroids inhibit the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblast precursors into mature osteoblasts. They also reduce osteoblast production of osteoid, the organic matrix of bone.

2. Direct stimulation of bone resorption by osteoclasts: Osteoclasts are cells that break down bone. Steroids activate osteoclasts, increasing the rate of bone resorption. This imbalance between bone formation and resorption results in bone loss over time.

3. Reduced intestinal calcium absorption: Steroids inhibit calcium absorption in the gut by acting on vitamin D and intestinal cells. Less calcium is taken up from the diet, resulting in lower calcium levels in the blood. This stimulates the release of parathyroid hormone which breaks down bone to maintain blood calcium.

4. Increased renal calcium excretion: Steroids act on the kidneys to increase excretion of calcium into the urine. This contributes to lower blood calcium levels and stimulation of bone resorption.

5. Inhibition of sex steroids: Steroids reduce the production of gonadal sex steroids like estrogen in women and testosterone in men. Estrogen in particular is important for maintaining bone density in women. Lower estrogen levels lead to accelerated bone loss.

6. Reduced growth hormone: Steroids inhibit the release of growth hormone from the pituitary. Growth hormone stimulates bone growth and regeneration. Lower levels therefore reduce these effects, contributing to bone loss.

The mechanisms summarized above all act together to significantly impact bone remodeling and tilt the balance toward bone loss and osteoporosis development with long term corticosteroid use. The rate and severity of bone loss depends on factors like:

• Dose and duration of steroid therapy

• Underlying condition being treated

• Patient age and menopause status

• Initial bone density

• Use of calcium, vitamin D and antiresorptive drugs

To minimize osteoporosis, lowest effective steroid doses are used, calcium and vitamin D are supplemented, and antiresorptive drugs are often provided for those at high risk. Monitoring of bone density is also recommended to detect significant bone loss over time.

Q. Side effects of steroids will you need to counsel patient about?

When prescribing corticosteroids like prednisone, it is important to counsel patients about potential side effects and how to minimize them. Key points to discuss include:

• Acne, oily hair and skin: Can be managed with over-the-counter treatments. Wash frequently with mild cleanser.

• Blurred vision and cataracts: Report any vision changes to doctor. Cataract surgery may be needed long term.

• Glaucoma: Steroids can increase eye pressure. Monitor with regular eye exams, especially if personal or family history of glaucoma.

• Easy bruising and wound healing: Take care to avoid injuries. Inform doctors doing procedures that patient is on steroids.

• Hypertension: Monitor blood pressure regularly. Antihypertensives may be needed to control high blood pressure.

• Diabetes: Monitor blood sugars frequently, especially when starting or increasing steroids. Oral medications or insulin may be required to control hyperglycemia.

• Increased appetite and weight gain: Diet and exercise can help limit weight gain. Referral to nutritionist for diet advice may be useful.

• Hirsutism: Excess body and facial hair growth is temporary but distressing for some women. Hair removal treatments can be tried. Resolves once steroids stopped.

• Insomnia and restlessness: Avoid steroids in evening when possible. Sedatives can be used short term but dependence risk with long term use. Melatonin or lifestyle changes may help establish better sleep schedule.

• Muscle weakness: Monitor for difficulty climbing stairs, rising from chairs, etc. Physical therapy or walking aids may provide assistance. Condition usually improves once steroids reduced or stopped but may take many months.

• Osteoporosis: Calcium, vitamin D and bisphosphonates are often used prophylactically to prevent bone loss. Monitor with DEXA scans and manage risk factors like low body weight, smoking, etc.

• Stomach irritation: Proton pump inhibitors or H2 blockers commonly co-prescribed with steroids to reduce risk of ulcers and GI bleeds, especially with high doses or long term use.

• Mood changes: Can include depression, irritability, euphoria or mood swings. Usually temporary but psychological support may help for some patients. Symptoms often improve with steroid dose reduction.

• Fluid retention: Limit salt and monitor weight. Diuretics may be needed short term for severe fluid retention, especially around chest or heart. Leg swelling common and elevation, compression stockings can provide relief.

Patients should understand side effects are often temporary, but some may persist long term or require treatment. Close monitoring and follow up, especially when first starting or increasing steroids, can help detect side effects early and manage them properly to improve tolerability and reduce complications. Dose should be lowest possible to control the underlying condition.

Q. Lady then has a fall and fractures her hip. What are the likely causes in this situation?

In an elderly woman, osteoporosis is the most likely underlying cause of a hip fracture from a fall. Key points:

• Osteoporosis refers to weak and porous bones due to loss of bone mineral density and disruption of bone microarchitecture. It makes bones more fragile and susceptible to fracture.

• Postmenopausal women are at highest risk due to decreased estrogen levels which accelerate bone loss. Other risk factors include:

– Age over 65 years: Risk increases with age as bone loss outpaces bone formation.

– Low body weight: Less mechanical stress on bones slows new bone formation.

– Family history: Genetics account for up to 85% of bone density and osteoporosis risk.

– Sedentary lifestyle: Weight-bearing exercise stimulates bone formation and growth. Inactivity promotes bone loss.

– Excessive alcohol or smoking: Both accelerate bone loss and the breakdown of bony matrix.

– Vitamin D deficiency: Needed for calcium absorption and bone mineralization. Supplements are often advised.

– Hyperthyroidism or hyperparathyroidism: Excessive bone resorption and turnover weakens bone. Treatment addresses the hormonal disorder.

• In the setting of severe osteoporosis, the minimal trauma from a fall can cause bones to fracture. The hip (femur) is a common site of fracture as it supports much of the body’s weight.

• Hip fractures in the elderly often require surgery to stabilize the bone and enable early mobilization, as prolonged bed rest can have detrimental health effects. Recovery depends on severity but may be prolonged over months.

• Following a hip fracture, diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis is important to prevent future fractures. This includes:

– Bone density testing by DEXA scan. Goal is to determine level of bone loss and fracture risk.

– Calcium and vitamin D supplementation. Bisphosphonates like alendronate are first-line.

– Follow up bone density testing. To monitor treatment response and determine if/when drug therapy changes are needed based on bone loss stabilization or continuing decline.

– Fall prevention. Reducing falls is key since bones remain weakened. Physical therapy, medication review, home safety evaluation, and exercise programs can all help lower fall risk.

Q. What is pathological fracture?

A pathological fracture occurs when abnormal or diseased bone breaks following minimal or no trauma. Key points:

• Pathological fractures develop due to an underlying bone disease that has weakened the bone, such as:

– Osteoporosis: Reduced bone density and disrupted microarchitecture make bone more prone to fracture.

– Metastatic bone disease: Cancerous tumors in the bone destroy normal bone tissue and predispose to fracture.

– Paget’s disease: Excessive bone breakdown and formation results in bone that is structurally disorganized and weaker.

– Osteomalacia: Deficiency of vitamin D and calcium leads to decreased mineralization of bone matrix, resulting in soft and pliable bones that fracture easily.

• Fractures can occur during normal activities of daily living like walking, bending or twisting that would not normally break a healthy bone. Severe fractures can even occur spontaneously without trauma.

• The risk of pathological fracture depends on the severity of bone loss or damage, and which bones are affected. Vertebral compression fractures are most common with osteoporosis, while long bone fractures more often occur with cancers that metastasize to bone.

• Diagnosis is made through history, physical exam and imaging studies:

– X-rays show the fracture line and characteristics of the underlying bone disease like osteopenia, lytic lesions or bone destruction.

– DEXA scan measures bone density to diagnose conditions like osteoporosis.

– CT or MRI provide detailed views of bone anatomy and patterns of destruction from metastases or infections.

– Blood tests determine levels of calcium, phosphorus and bone markers to distinguish different bone diseases.

• Treatment focuses on the underlying bone disease and preventing future fractures:

– Osteoporosis: Bisphosphonates, denosumab, teriparatide to improve bone density and strength. Calcium and vitamin D.

– Bone metastases: Radiation therapy, surgery and/or internal fixation of the fracture. Systemic therapy for the cancer.

– Paget’s disease: Bisphosphonates or denosumab to slow bone turnover. Surgery if deformity or fracture.

– Osteomalacia: High dose vitamin D and calcium to remineralize bone. Treatment of the underlying cause of deficiency.

So in summary, pathological fractures occur in diseased bones that have become weak, often fracturing due to minimal trauma or normal stresses. Diagnosis and treatment should focus on determining and managing the underlying bone disease, in addition to standard fracture care. Improving bone density and strength, controlling bone destruction from metastases and correcting nutritional deficiencies can help lower fracture risk.

Q. Other causes of pathological fracture?

There are many causes of pathological fractures other than osteoporosis. Some key ones include:

• Skeletal metastases: Cancer that has spread to the bones can weaken them and increase fracture risk. Common primary cancers include breast, prostate, lung and kidney. Fractures often occur spontaneously or with minimal trauma.

• Paget’s disease of bone: Excessive bone resorption and formation leads to disorganized, weakened bone structure. Most common in pelvis, spine, skull, femur. Increased fracture risk.

• Multiple myeloma: Uncontrolled proliferation of plasma cells within bone marrow cavities causes lytic bone lesions, bone pain, and fractures. Usually involves spine and pelvis.

• Rickets and osteomalacia: Deficiencies in vitamin D and calcium impair bone mineralization, leading to soft, weak bones prone to deformity and fracture. More common in children (rickets) but can occur in adults (osteomalacia).

• Hyperparathyroidism: Excess PTH causes increased bone resorption, bone loss and weakness. Fracture risk is 2-3 times higher, especially in vertebrae, ribs and femoral neck.

• Radiation therapy: Destroys bone cells and inhibits new bone formation in the radiation field. Can increase fracture risk by up to 67% depending on site and dose. May occur years after initial treatment.

• Long term steroid use: Glucocorticoids inhibit bone formation and increase resorption. Significant dose and duration dependent increased fracture risk at multiple sites, including vertebral compression fractures common.

• Osteogenesis imperfecta: Genetic collagen defect impairs bone matrix formation and mineralization. Four types ranging from mild to lethal. Even mild forms have increased fracture frequency, especially in long bones and spine.

• Other causes: Renal osteodystrophy (from chronic kidney disease), immobilization, neurogenic causes (from paralysis), chemotherapy, hyperthyroidism and hypogonadism can also contribute to bone weakening and increased pathological fracture risk.

The underlying disease, affected bones, clinical course, and radiologic findings help determine the cause of pathological fractures from multiple potential aetiologies. Targeted treatment of the primary bone condition, in addition to fracture management, can help stabilize bone health and lower future fracture risk. Careful monitoring and follow up is also needed due to the possibility of multiple fractures or complications.

Q. What is osteoporosis?

• Osteoporosis is a metabolic bone disease characterized by decreased bone mineral density (BMD) and deterioration of bone microarchitecture, leading to increased bone fragility and susceptibility to fractures.

• Diagnosis is based on BMD at least 2.5 standard deviations below the mean peak bone mass for young adults (T-score of -2.5 or lower) measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan.

• Common symptoms include back pain from compression fractures, loss of height over time and bone deformities. Fragility fractures of the hip, spine and wrist are often the first signs, even without preceding symptoms.

• Normal calcium, phosphorus and alkaline phosphatase levels help rule out other bone disorders. Vitamin D deficiency is common and should be corrected.

• Treatment options include:

› Bisphosphonates: Inhibit bone resorption, such as alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate and zoledronic acid.

› Hormone therapy: Estrogen therapy for women can prevent further bone loss and reduce fracture risk.

› Denosumab: Monoclonal antibody that inhibits osteoclast formation and function.

› Teriparatide: Recombinant parathyroid hormone that stimulates new bone formation. Used for severe osteoporosis.

› Strontium ranelate: Trace element that both builds bone and inhibits resorption. Not available in some countries.

› Lifestyle changes: Adequate calcium/vitamin D, exercise, limited alcohol/smoking, fall prevention.

• Follow up includes repeat BMD testing, usually within 2 years of treatment initiation and every 2 years thereafter to monitor treatment response and fracture risk. Medication or dosage adjustments are made based on bone density changes.

• Prevention through diet, exercise, lifestyle and risk factor management beginning in childhood and continued lifelong provides the optimal means of maintaining bone strength and independence as we age. But it’s never too late to adopt bone-healthy habits.

Osteoporosis is a serious but preventable and manageable disease with a range of treatment options for slowing or stopping progression. Comprehensive care coordinated among providers and patient participation through lifestyle approaches offer the best solutions for fracture prevention at all life stages.

Q.Causes of osteoporsis in this case ?

there are several significant risk factors for osteoporosis in this case:

1. Female sex: Women have lower peak bone mass and experience accelerated bone loss in the years following menopause due to decreased estrogen levels. Postmenopausal women have a high risk of osteoporosis and fractures.

2. Menopause: The drop in estrogen after menopause causes rapid bone loss of up to 20% in the 5 to 10 years after menopause. This contributes significantly to osteoporosis risk in older women.

3. Age over 60: The risk of primary osteoporosis increases with age as bone loss outpaces bone formation. The prevalence of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures rises steeply in both men and women age 60 and older.

4. Long term steroid use: Chronic use of corticosteroids inhibits bone formation and increases bone resorption, leading to osteoporosis and fragility fractures, especially with higher doses and longer durations of use. Even low dose inhaled steroids may increase risk when used long term.

5. Other possible contributors:

• Genetics: A family history of osteoporosis or fractures also increases risk. Certain populations are more prone to bone loss and fracture.

• Low BMI: Thin or small-boned body frames provide less support for bone density and structure. Weight gain, when underweight, may help reduce osteoporosis risk.

• Inactivity: Lack of regular exercise or immobility from medical conditions can accelerate bone loss due to disuse and deterioration. Weight-bearing and resistance exercise mitigate this and build bone strength.

• Falls: Previous fractures from falls, especially from heights, contribute to vulnerability for future fractures in the setting of weakened bone. Fall prevention and balance/strength exercise help reduce the likelihood of falls and re-fractures.

• Medical causes: Other conditions like overactive parathyroid, coeliac disease, and hyperthyroidism need to be investigated as potential contributors to secondary osteoporosis. Management of these conditions may help stabilize bone loss.

Q. Pathophysiology of osteoporosis?

The key points include:

1. Osteoporosis is a metabolic bone disease characterized by decreased bone mineral density (BMD) and deterioration of bone microarchitecture. This results in increased bone fragility and susceptibility to fractures.

2. The hallmarks are loss of bone matrix and disruption of trabecular bone connectivity and orientation, leading to bone that is less dense, less rigid and more porous.

3. There are 3 main mechanisms underlying development of osteoporosis:

• Failure to achieve optimal peak bone mass during growth: Genetics and lifestyle factors like diet, exercise and hormone levels during development determine peak bone mass. Insufficient bone accumulation leaves less reserve available later in life.

• Excessive bone resorption from osteoclast over activity: Imbalance between bone resorption and formation, especially with aging and in postmenopausal women, causes bone loss at a rate that outpaces new bone development.

• Impaired bone formation from osteoblast deficiency: Conditions such as aging, inflammation, medications (like glucocorticoids) and immobility can inhibit bone formation by osteoblasts. This also contributes to bone fragility.

4. Most rapid phase of trabecular bone loss occurs in the first 3 to 5 years of menopause when estrogen deficiency accelerates bone resorption. Loss of cortical bone predominates later in life in both men and women.

5. Age-related bone loss begins around age 30-40, even before menopause, as bone formation slows down and resorption continues at the same pace. This leads to a gradual decline in BMD over many years.

6. Multiple factors, including hormones, cytokines, growth factors and mechanical loading, regulate the tightly coupled bone resorption by osteoclasts and bone formation by osteoblasts during remodeling. Imbalance in any regulators can contribute to osteoporosis development.

Q. Risk factors osteoporsis ?

Many important risk factors for osteoporosis and fractures:

• Female sex: Women have lower peak bone mass and more rapid bone loss after menopause. Estrogen deficiency is a major contributor to osteoporosis in women.

• Thin/small frame: Less bone mass to start with and less support for maintaining bone density over time. Low body weight, especially BMI <19, is a risk factor.

• Age over 50: Bone loss and microarchitectural deterioration accelerate after age 50 in both men and women. Risk rises substantially with advancing age.

• Family history: Genetic factors can determine peak bone mass and rate of bone loss. Maternal history of hip fracture, in particular, increases risk.

• Ethnicity: Osteoporosis and fracture rates tend to be higher in European and Asian populations. Hispanic and blacks also face risks, though lower than in whites.

• Smoking: Accelerates bone loss and inhibits calcium absorption. Both current and long-term past smoking are detrimental to bone health.

• Steroid use: Long term corticosteroid therapy inhibits bone formation and increases bone resorption. Risk is dose and duration dependent.

• Heparin: Long term use of heparin anticoagulants can lead to osteoporosis, in part because it interferes with vitamin K and bone mineralization.

• Excessive alcohol: Alcohol disrupts bone remodeling, inhibits bone cell activity and nutrient absorption, and promotes parathyroid hormone. More than 2 drinks/day raises risk.

• Low calcium/vitamin D: These key nutrients are essential for building and maintaining strong bones. Deficiency, especially vitamin D, contributes significantly to higher osteoporosis risk.

• Sedentary lifestyle: Lack of weight bearing exercise causes loss of bone density due to disuse. Inactivity both earlier in life and currently adds risk. Regular exercise prevents this and builds stronger bones.

• Other factors: Gastrointestinal problems, rheumatoid arthritis, hyperthyroidism, chemotherapy, and long term PPIs or SSRI antidepressants may also foster bone loss and increase osteoporosis risk.

Q. Lady subsequently needs a surgery. What are concerns for this lady undergoing operation?

1. Long term steroid use: Patients on chronic corticosteroid therapy may need perioperative stress dose steroids to prevent adrenal insufficiency during the stress of surgery and anesthesia. Failure to supplement can lead to an Addisonian crisis which is a medical emergency.

2. Undiagnosed adrenal insufficiency: In patients with unrecognized or untreated adrenal failure from conditions like Addison’s disease, the adrenals may not produce enough cortisol to respond to surgical stress. This can also precipitate a life-threatening Addisonian crisis if not properly managed.

3. Abrupt discontinuation of steroids: Stopping steroid therapy abruptly can lead to secondary adrenal insufficiency due to adrenal gland suppression. During surgery and recovery, the adrenals may not recover quickly enough to meet increased cortisol demands, resulting in crisis.

To address these concerns, several precautions should be taken:

1. Review the patient’s usual steroid regimen and dosing. Administer stress dose steroids (e.g. hydrocortisone 100 mg IV q8h) perioperatively based on steroid potency and duration of use.

2. For patients on long term steroids, especially > 5-10 mg prednisone equivalent daily for months, give a bolus of IV hydrocortisone during surgery induction and continue scheduled IV or oral steroids post-op.

3. Have intravenous or preoperative ‘just in case’ steroids and fluids available for poorly controlled Addison’s disease or adrenal suppression patients at high risk of crisis.

4. Carefully monitor for signs of adrenal insufficiency like hypotension, nausea, weakness and altered mental status which can progress rapidly if not treated. Immediately give IV hydrocortisone if crisis develops.

5. Educate patient to never abruptly stop or miss scheduled steroid therapy, especially prior to procedures. Proper communication with all care providers about exact steroid regimen is crucial.

6. For elective surgery, if possible, aim for morning procedure when cortisol levels are naturally highest to minimize demand on potentially impaired adrenal function.

7. Where adrenal function uncertain or reserves depleted, screening may include AM cortisol, ACTH stim test or other adrenal function studies, if feasible and findings could alter management.

With proper preparation and precautions taken, risk of life-threatening adrenal crisis can be minimized for patients with potential adrenal impairment undergoing surgery and anesthesia. A planned, monitored approach is essential given the severe consequences of insufficient response to surgical stress in this population.

Q . What precautions to prevent this. ?

Precautions to prevent an Addisonian crisis in this patient undergoing surgery:

1. Increase steroid dose prior to surgery: For patients on long term steroids, the usual maintenance dose should be increased in the perioperative period based on the potency and duration of their regimen. This is to provide additional cortisol to meet the increased demands of surgical stress.

2. Convert to IV hydrocortisone: Oral steroids should be temporarily switched to IV hydrocortisone (e.g. 100 mg IV q8hrs) on the day of surgery to ensure adequate absorption and effect. IV administration allows for more rapid adjustment of doses as needed in the perioperative and immediate post-operative period.

3. Thorough history and communication: Take a complete medical history with full details of the patient’s usual steroid therapy. Communicate with the surgeon, anesthesiologist, intensive care staff and all relevant providers about the patient’s adrenal status and steroid dosing needs to minimize the risk of errors or omissions, especially during transitions of care.

4. Close monitoring in higher care unit: For high risk patients or complex surgeries, admission to an intermediate or intensive care unit for close post-operative monitoring may be warranted. More frequent cortisol levels, vital signs and clinical review can identify a crisis early.

5. Emergency supplies and management at hand: Have injectable hydrocortisone, IV fluids and other supplies ready for immediate use in case the patient shows signs of a crisis. Emergency management includes prompt IV hydrocortisone and aggressive rehydration and correction of electrolyte imbalance and/or hypotension.

6. Patient education about steroid management: Educate the patient to never abruptly stop steroids for any reason, including prior to procedures. Reinforce that daily steroids are life-sustaining and must be taken as prescribed to prevent adrenal crisis, especially when having medical or dental treatment.

7. Consider pre-op ACTH stimulation testing: Where adrenal function is uncertain or depleted, preoperative ACTH testing may help in risk stratification and steroid dose planning, where possible, for the safest perioperative management.

Prevention of crisis involves comprehensive preparation based on knowledge of the patient’s adrenal status and usual steroid replacement needs. Anticipating increased requirements ahead of surgery and providing supplemental IV steroids, clinical monitoring and emergency management resources minimize the risks. Thorough communication and patient understanding about lifelong maintenance of daily steroid therapy are also essential for safety.

Q. How will you manage her hip fracture? Do you have to do anything about GCA before Hip fracture surgery?

1. Preoperative assessment: This should include:

• History of steroid use including current regimen, duration and compliance.

• Physical exam: Look for signs of adrenal insufficiency like hypotension, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia or hypoglycemia.

• Laboratory tests: CBC, electrolytes, renal and liver function, glucose, cortisol (AM and possibly ACTH stim test or ITT if adrenal function uncertain).

• Short Synacthen test may be done to assess adrenal responsiveness and need for perioperative steroids, if feasible in the preoperative setting.

2. Perioperative steroid management based on surgery severity:

• Minor surgery: Continue usual steroids. May give 25 mg IV hydrocortisone at induction.

• Moderate surgery: Usual preop steroids plus 25 mg IV hydrocortisone at induction and q8h for 24 hrs.

• Major surgery: Usual preop steroids plus 50 mg IV hydrocortisone at induction and q8h for 48-72 hrs postop or until eating, then restart normal steroid schedule.

3. Intraoperative precautions: Have IV hydrocortisone, fluids and supplies on hand in case of crisis. Carefully monitor clinical status, blood pressure, fluids. Communicate steroid needs with anesthesiologist and surgical team.

4. Postoperative care: Continue scheduled IV or switched back to oral steroids as per protocol for surgery severity. Frequent clinical review and monitoring for 2-3 days in higher care unit for major surgeries or in complex patients at high risk of crisis.

5. Hip fracture management: In addition to steroid management, timely surgical fixation of the hip fracture is needed to allow early postoperative mobilization and weight bearing as tolerated based on procedure. Physiotherapy review and bone health management will also be part of rehabilitation and discharge planning.

6. Osteoporosis management: Perioperative IV bisphosphonate, calcium, Vit D should continue. Oral osteoporosis agents may need to be temporarily held in the post-operative period if unable to take medications orally. Lifestyle factors like smoking cessation, limited alcohol and weight bearing exercise remain part of the long term strategy once recovered from surgery.

With comprehensive preoperative preparation, careful intraoperative and postoperative monitoring in the acute setting, properly managed steroids based on severity of surgery and treatment of the underlying hip fracture, risks of Addisonian crisis can be minimized and recovery optimized in this complex patient. Long term strategies for preventing future fractures are also essential for improved mobility and quality of life.

Q. SOB and petechae after THR/ patient died POD-1, diagnosis?

1. Shortness of breath (SOB) and petechiae (small red/purple spots on skin) are characteristic signs of fat embolism syndrome.

2. Fat embolism occurs when fat droplets are released into the bloodstream, usually from broken long bone fractures or orthopedic procedures like joint replacement involving significant manipulation of long bones like the femur.

3. In the case of THR, reaming of the femoral canal, impaction of acetabular and femoral components and manipulation/repair of fractures during the procedure can all introduce fat into circulation.

4. The fat emboli then travel to the small vessels of the lungs, causing inflammation and impaired oxygen exchange resulting in hypoxemia, and can distribute to other organs as well.

5. Symptoms of respiratory distress, petechiae, confusion/altered consciousness along with drop in oxyhemoglobin saturation and bilateral infiltrates on CXR confirm the diagnosis.

6. While most cases of fat embolism are subclinical or cause relatively mild symptoms, severe cases can culminate in ARDS, multiorgan failure and even death, as potentially occurred in this patient.

7. management is supportive, focusing on maintaining oxygenation and perfusion. This includes mechanical ventilation, fluid management vasopressor support, and supplemental oxygen. Steroids may reduce inflammation.

8. Usually symptoms appear 12-36 hours following injury or surgery, so early postoperative period monitoring for signs of fat embolism in high risk patients is critical.

9. Early fixation of long bone fractures and careful surgical technique may help limit fat embolus burden, but some degree of fat embolism is unavoidable with major orthopedic procedures involving significant bone manipulation.

In summary, while rare, fat embolism syndrome is a potentially serious post-operative complication, especially following procedures involving long bone trauma or surgery such as this THR procedure. Respiratory manifestations predominate and anticipation of symptoms within 1-2 days permits early detection and management in most cases. Unfortunately, in some patients the fat embolus may be massive enough to overwhelm attempts at support, leading to rapid deterioration and even death, as you have described in this case.

Q .Causes of fat embolism ?

sSeveral major causes of fat embolism:

1. Long bone fractures: Closed fractures of the long bones (femur, tibia, humerus) release fat droplets from the marrow into circulation. This is one of the most common causes of clinically significant fat embolism.

2. Orthopedic procedures: Any surgery involving manipulation of long bone marrow content like reaming, nailing or joint reconstruction/replacement can introduce fat into the bloodstream. Total hip arthroplasty, as in the case discussed, is a prime example.

3. Severe burns: Extensive burns, especially those over areas covering long bones, release fat from the bone marrow. Fatty acids may also enter circulation from damaged adipose tissue.

4. Pancreatitis: Inflammation and damage to fatty tissues in acute pancreatitis leads to release of free fatty acids into the blood. These fatty emboli can contribute to respiratory failure and multisystem organ dysfunction in severe cases.

5. Diabetes mellitus: Poorly controlled diabetes with ketoacidosis causes lipolysis and release of free fatty acids into the circulation which can coalesce into fat emboli, especially when another inciting factor like trauma or surgery is present.

6. Decompression sickness: Rapid decompression of a hyperbaric environment leads to bubble formation, including fat emboli, which can occlude blood vessels and cause a distinct symptom complex known as ‘the bends.’ Recompression reverses the process.

7. Cardiopulmonary bypass: The trauma of establishing bypass during open heart surgery is hypothesized to trigger fat embolism in some cases, likely from instrumentation of long bone marrow depots like the iliac crest used for femorofemoral bypass cannulation.

8. Miscellaneous: Additional rare causes include hepatic/biliary disease, sickle cell crisis, liposuction and bone tumor emboli (from primary bone tumors or bony mets).

Q.How to manage fat embolism?

Key principles in managing fat embolism syndrome:

1. Supportive respiratory care: This includes supplemental oxygen, close monitoring of respiratory status and oxyhemoglobin saturation and early institution of mechanical ventilation for significant hypoxemia or respiratory failure. PEEP and lung protective ventilation strategies may be needed in case of ARDS.

2. Fluid and electrolyte management: Careful fluid balance is important to manage acute lung injury without overloading the lungs. Kare should be taken to correct any electrolyte imbalance, particularly maintaining normal serum calcium which can drop in fat embolism.

3. Prevention of complications: Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis with heparin or compression stockings and treatment of sepsis if develops decreases secondary complications. Early nutritional support via enteral or parenteral feedings also aids in recovery.

4. Specific unproven treatments: Some advocated but unproven therapies for fat embolism include:

• Ethanol infusion: Aiming to dissolve fat droplets, but no strong evidence for benefit and risk of toxicity. Not recommended currently.

• Dextran 40: Previously thought to bind fat droplets and facilitate clearance, but studies show no benefit and significant risk of anaphylaxis or bleeding with use. Not substantiated.

• Heparin: While heparin prophylaxis to prevent DVT may be used, there is little evidence that therapeutic doses of heparin help in clearing fat emboli or reducing sequelae. Risks may outweigh benefits.

• Steroids: Corticosteroids may reduce inflammatory damage from fat emboli but also remain controversial with no clear evidence for or against their use. Some clinicians use short moderate dose taper, but routine use not validated.

In summary, management of fat embolism syndrome remains primarily supportive. Supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation as needed based on clinical severity, fluid management to support circulating volume without overloading and early nutritional repletion should be initiated in all cases. Monitoring for common complications allows prompt intervention. Other treatments remain controversial without solid evidence to justify risks. Key is early detection when symptoms first arise after a precipitating event.

Q .criteria of fat embolism ?

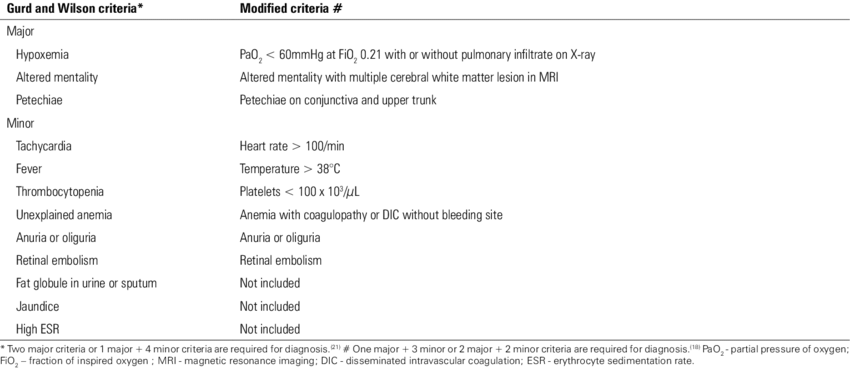

Gurd’s Criteria: Most widely used, requires at least one major clinical feature along with an inciting event.

Q.Describe about Multiple Myeloma and Bence Johns Protein?

1. Multiple myeloma is a plasma cell malignancy. Plasma cells are a type of white blood cell responsible for antibody production. In myeloma, malignant plasma cells accumulate in the bone marrow.

2. Clinical features result from displacement of normal bone marrow by plasma cells and secretion of M proteins:

• Bone pain, fractures: Lytic lesions, osteoporosis and compression fractures.

• Anemia: From bone marrow failure and hemolysis. Normocytic normochromic.

• Renal failure: From light chain cast nephropathy, dehydration and hypercalcemia.

• Recurrent infections: Due to immune deficiency from abnormal antibody production.

• Hypercalcemia: From lytic bone lesions and excess PTHrP production.

• Amyloidosis: Deposition of abnormal proteins in tissues. Affects heart, kidneys, liver, GI tract.

3. Diagnosis is based on:

• Serum and urine electrophoresis: Detect M spike (IgG 55%, IgA 25%) and light chains.

• Bone marrow biopsy: Shows >10% clonal plasma cells.

• Lytic lesions on x-ray: Punched out lesions, especially skull.

• High serum calcium, creatinine and low Hb as per the CRAB criteria.

4. Staging uses serum beta-2 microglobulin, albumin and number/severity of lytic bone lesions. Durie-Salmon and International Staging System (ISS) are commonly used.

5. Treatment options include:

• Chemotherapy: Melphalan and prednisone for early stage, bortezomib, lenalidomide and steroids for relapsed/refractory disease.

• Stem cell transplant: For eligible patients, high dose melphalan chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell rescue.

• Radiation therapy: For localized bone pain or imminent fracture.

• Bisphosphonates: Help reduce bone loss and risk of fractures.

• Supportive care: Includes IV fluids, antibiotics, transfusion support as needed.

The outlook for myeloma depends on disease stage and age. While incurable, modern therapies have significantly improved survival from a few months to over 5-10 years with good quality of life for many patients. Ongoing research continues to lead to new promising options for management of this complex plasma cell cancer.

The CRAB criteria are used to define symptomatic multiple myeloma requiring treatment. CRAB stands for:

C – Calcium elevation: Serum calcium > 0.25 mmol/L (> 1 mg/dL) above the upper limit of normal or > 2.75 mmol/L (> 11 mg/dL)

R – Renal insufficiency: Creatinine clearance < 40 mL/min or serum creatinine > 177 μmol/L (> 2 mg/dL)

A – Anemia: Hemoglobin < 10 g/dL or 2 g/dL below the lower limit of normal

B – Bone lesions: Lytic bone lesions, severe osteopenia or pathologic fractures on skeletal radiography, CT or PET-CT

Any one or more of these findings in the presence of clonal bone marrow plasma cells or a plasmacytoma confirms the diagnosis of symptomatic or active multiple myeloma requiring treatment.

The specifics of the CRAB criteria are:

Calcium: Hypercalcemia results from excess bone destruction and PTHrP release. Corrected calcium is calculated based on albumin level.

Renal: Due to light chain cast nephropathy, dehydration or hypercalcemia. Creatinine clearance reflects GFR more accurately than serum creatinine alone.

Anemia: Normocytic, normochromic anemia results from marrow displacement by plasma cells and cytokine-related bone marrow suppression.

Bone: Lytic lesions, osteoporosis or fractures detected by skeletal survey (plain x-rays), CT, MRI or PET-CT. Osteopenia alone without fractures can qualify.

These criteria capture the essence of symptomatic, active myeloma which requires treatment to prevent end organ damage and disease complications. Not all criteria need be met simultaneously, and the specific parameter values may vary in different staging systems. But they provide a framework for determining when myeloma has become clinically significant enough to warrant anti-myeloma therapy.

Staging systems like Durie-Salmon and ISS further incorporate factors like plasma cell labeling index, serum beta-2-microglobulin and albumin to provide prognostic information and guide management approach. But the CRAB criteria remain a simple, memorable tool for initial assessment of myeloma symptomatology and need for treatment.

1. Bence Jones proteins are monoclonal free light chains found in the urine. They are produced by neoplastic plasma cells in the bone marrow, most commonly due to multiple myeloma.

2. The light chains (kappa or lambda) are normally bound to heavy chains as part of intact immunoglobulins (antibodies). In myeloma, excess production of light chains by malignant plasma cells and impaired kidney function leads to spillover into the urine.

3. Patients typically excrete only kappa or lambda light chains. This reflects that all plasma cells in a given patient’s myeloma clone produce either kappa or lambda light chains, but not both.

4. Light chains in the urine may cause:

• Renal failure: Light chain cast nephropathy from precipitation of Tamm-Horsfall protein. This impairs kidney function further, perpetuating more light chain excretion.

• Dehydration: Significant volumes of urine may be produced leading to hypovolemia and electrolyte imbalance if not adequately hydrated.

• Amyloidosis: Light chains can deposit in tissues as amyloid fibrils, damaging organs like the heart, liver, nerves and GI tract.

5. Diagnosis of Bence Jones proteinuria involves:

• Urine electrophoresis: Shows a monoclonal M spike in the kappa or lambda region.

• Urine immunofixation: Confirms the kappa or lambda nature of the protein.

• 24 hour urine quantitation: Measures total light chain excretion which aids prognosis and treatment monitoring. Levels >500 mg/day indicate higher disease activity.

• Urine protein electrophoresis index (UPE index): Ratio of kappa to lambda in the urine. In myeloma, ratio is very high or low due to excretion of a single light chain type.

• Urine light chain ratio: As above, normal ratio is 0.26-1.65. Deviations indicate excess production of either kappa or lambda light chains.