Skin Cancers : Melanoma/ BCC/ SCC

Q. Describe lesion ?

10 mm Pearly papule with a central ulcer with granulation tissue on base and rolled in/ Inverted edges with surrounding telangiectasia

The description of the lesion suggests features consistent with a basal cell carcinoma (BCC):

1. 10 mm size: BCCs are typically >5mm in size by the time a patient notices them or seeks medical attention. They tend to grow slowly over weeks to months.

2. Pearly papule: BCCs often appear as raised pearly or waxy papules or nodules with a smooth, shiny surface. This is due to accumulation of abnormal basal cells in the dermis.

3. Central ulceration: As BCCs enlarge, the central area may ulcerate or develop granulation tissue due to breakdown of tumor cells. The border then appears rolled or sloped into the ulcer bed.

4. Rolled, invertd edges: BCC borders are typically raised, rounded and appear rolled inward towards the center of the lesion. This is described as a “pearly rolled edge”. The sloping and inverted profile is a key feature.

5. Telangiectasia: Abnormal blood vessels surrounding the BCC, visible as threadlike red lines on the skin surface, develop to supply the growing tumor. Their appearance, especially clustered around the lesion border, adds to the BCC picture.

6. Slow growing: Most BCCs enlarge over a period of 2-3 months up to years as was likely the case here based on the features described. Their indolent nature is why early detection is critical.

7. Locally invasive: While BCCs rarely metastasize, they are locally invasive and destroy surrounding tissues. The longer they are left, the more extensive the removal and reconstruction required.

In summary, the clinical features described – a 10mm pearly papule with central ulceration and rolled edges, surrounded by prominent blood vessels and having grown over months – are highly suggestive of a basal cell carcinoma. On the face, BCCs require urgent removal with particular tissue-sparing techniques like Mohs micrographic surgery to maximize preservation of function and cosmesis. Once excised, regular follow up and sun protection minimize risks of recurrence which are higher in the previously affected area.

Q. Why the surrounding skin is red?

The surrounding skin redness and presence of telangiectasia (dilated superficial blood vessels) around a basal cell carcinoma is primarily due to:

1. Angiogenesis: As a BCC grows, it recruits its own blood supply to provide oxygen and nutrients to the tumor cells. This results in the development of new abnormal blood vessels surrounding and within the lesion. These feeder vessels are visible through the skin, giving the characteristic appearance of telangiectasia.

2. Inflammation: The enlarging BCC causes local tissue damage, cell breakdown and minor bleeding which leads to an inflammatory response. Inflammation appears as erythema (redness) and minor swelling surrounding the lesion. This reaction contributes to the reddened, slightly raised appearance of skin adjacent to an established BCC.

3. Skin stretching: As a BCC expands over time within the dermis, it causes stretching of the overlying epidermis and minor separation from underlying tissues. This can enhance visibility of the superficial vascular structures in and around the lesion, accentuating the telangiectatic appearance and surrounding redness.

In summary, the key factors contributing to the appearance of dilated blood vessels and redness surrounding an enlarging BCC are:

1. Angiogenesis: Formation of abnormal new blood vessels to supply the growing tumor. These appear as telangiectasia around the lesion border.

2. Inflammation: Local inflammatory response to tissue damage and minor bleeding from the BCC. Results in erythema and minor swelling adjacent to the lesion.

3. Skin stretching: Expansion of the BCC within the dermis causes stretching and subtle separation of the overlying epidermis, enhancing visibility of underlying vasculature.

While concerning in appearance, the surrounding telangiectasia and redness pose no direct threat. However, their presence indicates an enlarging and long-established BCC which requires prompt removal and histologic assessment to determine adequate excision. Early detection of BCCs is critical to minimize destruction and optimize cosmetic outcomes with treatment.

Q. Most propable diagnosis?

Based on the description provided of a 10mm pearly papule with central ulceration, rolled borders, prominent surrounding telangiectasia and slow growth over months, the most probable diagnosis is basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Key features pointing to a BCC include:

1. Pearly, waxy papule: BCCs often present as raised pearly or waxy nodules with a smooth, shiny surface. They contain abnormal basal cells accumulating in the dermis.

2. Central ulceration: BCCs may ulcerate centrally as they enlarge, with granulation tissue visible in the ulcer bed. The raised, rolled borders remain intact.

3. Rolled, inverted edges: BCC borders are typically raised, rounded and appear rolled inward. They slope gently into the center of the lesion rather than having sharp margins. This sloping, pearly rolled edge is characteristic.

4. Prominent telangiectasia: BCCs recruit their own abnormal blood supply as they grow, visible through the skin as clustered threadlike blood vessels, especially around the lesion border.

5. Slow growing: BCCs tend to slowly expand over months to years. Their indolent nature means they may be present for a long time before becoming noticeable enough for a patient to seek assessment.

6. Rare metastasis: While BCCs are locally invasive and can cause significant destruction without treatment, they very rarely metastasize. This makes early detection and removal critical to optimize outcomes.

7. Common location: BCCs most frequently develop on sun-exposed areas of the head and neck, especially the central face, nose, cheeks and ears. They are associated with cumulative UV sun damage.

In summary, the clinical history and characteristics described are most consistent with a basal cell carcinoma. BCCs have a highly characteristic appearance but require biopsy and pathologic assessment to confirm the diagnosis and adequacy of margins with removal. When detected early and excised properly, BCCs have an excellent prognosis but may require long term monitoring for recurrence.

Q. D/D?

Other diagnoses to consider based on the description include:

1. Actinic keratosis (AK): AKs are rough, scaly pre-cancerous lesions caused by sun damage. They are usually multiple, often keratotic and may occasionally become squamous cell carcinomas. Differentiated from BCC by more irregular borders, scaliness and tendency towards spontaneous resolution.

2. Seborrheic keratosis (SK): Benign lesions of unknown etiology, often multiple. They appear as raised, warty lesions with a “pasted-on” appearance and waxy surface. Differentiated from BCC by more irregular shape, brown pigmentation and lack of telangiectasia or ulceration. SKs are very common, especially in middle age and older.

3. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC): Like BCCs, SCCs also arise from sun exposure but are more aggressive with higher metastatic potential. Differentiated by more rapid growth, a firm and friable texture, erythematous borders and a tendency to keratinize and crust. SCCs are often preceded by AKs.

4. Verruca vulgaris: Common warts caused by HPV, appearing as rough, hyperkeratotic papules. Mostly in younger individuals and on hands/feet. Differentiated from BCC by walk, orange tone, and spread on to adjacent skin. Spontaneous resolution sometimes occurs.

Features arguing against these alternative diagnoses and supportive of a BCC include:

•A pearly, waxy surface rather than rough, scaly or verrucous

•Telangiectasia, indicating the BCC’s own blood supply which other lesions lack

•Rolled, sloping borders that are smooth rather than irregular or jagged

•Central ulceration which would not occur with SKs or warts

•Lack of pigmentation as seen with SKs

•Older age of patient, as BCCs are uncommon in younger individuals

•Location on chronically sun-exposed skin, especially the head and neck

While clinical examination provides strong evidence, a biopsy and histological assessment are needed to confirm the diagnosis and determine appropriate management. Treatment approaches differ for each of these potential diagnoses.

Q.Biopsy shows BCC .What findings to see in Report ?

Key findings that would support a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma on histopathology include:

1. Palisading of basaloid cells: BCCs are comprised of basaloid cells that tend to arrange themselves in palisades – rows of cells that are all aligned in the same direction. This orderly patterning of tumor cells is characteristic.

2. Extension into the dermis: BCCs originate from basal cells residing in the epidermis but then extend downwards into the dermis. The depth of invasion or how deeply into the dermis the BCC extends provides information on its more aggressive or advanced nature.

3. Peripheral palisading: The outermost layer of basaloid cells often align themselves perpendicular to the epidermis, parallel to the adjacent stroma. This pattern of palisading around the borders of the BCC is typical.

4. Connection to the epidermis: Most BCCs maintain a connection to the overlying epidermis as they arise from epidermal basal cells. They expand downwards while still continuous with the epidermis. Some more advanced BCCs may lose this connection.

5. Retraction clefting: The stroma surrounding the BCC may space from the adjacent dermis, providing a retraction space. This is due to disruption of attachments between the dermis and epidermis by the expanding BCC.

6. Ulceration: Centrally located BCCs may ulcerate as they enlarge, breaking through the overlying epidermis. Both the ulcer bed and adjacent epidermis will show basaloid proliferation.

7. Lack of cytologic atypia: Despite locally invasive behavior, BCC cells tend to have minimal cytologic atypia – they appear uniform with scant cytoplasm, round and often mimicking normal basal cells. Mitoses are rare.

8. Absence of squamous pearls: BCCs do not keratinize and form “squamous pearls” as seen with squamous cell carcinomas. They remain non-keratinizing.

9. Perineural or lymphovascular invasion: Rarely seen but indicates more aggressive behavior with higher risks of recurrence or metastasis. Requires particularly close follow up.

The histopathologic findings, especially degree of invasion, marginal clearance and presence of aggressive features determines appropriate management and follow up. Confirmation of the diagnosis and BCC subtype helps guide specific treatment recommendations.

Q. Natural hx of BCC?

The natural history of basal cell carcinoma includes:

1. Indolent, slow growth: BCCs tend to grow slowly over months to years. Their gradual progression means they are often present for a long time before becoming noticeable enough for patients to seek medical attention. This indolent nature also means they only rarely become life-threatening if left completely untreated.

2. Locally destructive: Although slow growing, BCCs are locally invasive and destroy surrounding tissues over time. The longer they remain, the more extensive the removal and reconstruction required. Without treatment, they can cause significant damage, especially on the face.

3. Very limited metastasis: BCCs have an extremely low tendency to metastasize, with metastasis thought to occur in 0.0028-0.55% of lesions. Some histologic subtypes like micronodular or morpheaform BCCs may be slightly more prone to metastasis but the risk remains very small.

4. Origin from follicular germ cells: BCCs arise from damage incurred by a subset of basal cells thought to originate from follicular germ cells – those that would normally give rise to hair follicles and associated structures. Exposure to UV radiation is the primary cause of mutations that initiate BCC formation from these cells.

5. Originate in hair follicles: Specifically, BCCs are believed to derive from outer root sheath cells of the hair follicle. These pluripotent cells are able to differentiate into various follicular structures. With UV damage, they lose control mechanisms for proliferation and give rise to BCCs.

In summary, the natural history of BCCs is one of prolonged indolence with local tissue destruction over many years but an extremely limited tendency to metastasize, even when very advanced. Their origin from follicular germ cells, especially outer root sheath cells, has been established. The primary factor that triggers loss of normal control of proliferation in these cells is chronic UV sun exposure.

While BCCs rarely become life-threatening, their locally destructive potential, especially on cosmetically and functionally sensitive areas of the face, requires early detection and treatment to optimize preservation of healthy tissue and minimize risks of recurrence.

Q. Treatment of BCC ?

A comprehensive approach includes:

Surgical options:

1. Curettage and Electrodessication: Useful for low-risk BCCs. Cannot assess margins, higher recurrence risk.

2. Excision: Standard excision with 4mm margins. Can reconstruct with flaps/grafts for larger defects. Margin control is limited.

3. Mohs micrographic surgery: Tissue-sparing technique using frozen section margin analysis. Highest cure rate (up to 99%) with maximal tissue preservation. For high-risk facial BCCs.

4. Cryosurgery: Non-invasive but cannot assess margins or biopsy. Higher recurrence risk. Mostly for low-risk BCCs.

Non-surgical options:

1. Radiation therapy: For patients unable to undergo surgery. Slower cosmetic outcomes with higher costs. Not first-line for most BCCs.

2. Topical 5-fluorouracil: For superficial BCCs. Higher recurrence rates so reserved for patients where surgery contraindicated.

3. Imiquimod: Also for superficial BCCs. Use short-term. Incomplete response in ~30%, then requires surgical intervention.

4. PDT (Photodynamic therapy): Using a photosensitizing agent like ALA or MAL activated by light. Variable clearance for deeper BCCs so often needs repeat treatments. More optimal for minimal risk lesions.

Treatment selection depends on:

1. BCC characteristics: Size, location, margins, aggression, subtype, recurrence. High-risk BCCs require techniques providing highest control like Mohs.

2. Patient factors: Age, comorbidities, work/activities, anxiety, cosmetic concerns. In those where surgery not possible or refused, non-surgical options may be trialed.

3. Available expertise: Mohs surgery provides superior outcomes but requires highly specialized training and equipment. Not available in all centers.

4. Reconstruction needs: Larger defects especially on face may require plastic surgery for optimal cosmetic and functional repair. This influences BCC excision technique.

5. Risk tolerance: For BCCs with significant risks of recurrence or metastasis if incompletely removed, a definitive and margin-controlled approach is needed. Lesser options may be satisfactory for minimal-risk BCCs in some patients.

Treatment of BCCs requires full assessment of tumor characteristics along with patient factors, available surgical/non-surgical options and expertise to determine optimal, individually-tailored management. Close follow up afterwards minimizes risks of recurrence. Patient education on sun protection and self-examination promotes early detection of new lesions.

Q. How would you manage deep margin involvement?

For a basal cell carcinoma with deep margin involvement on histopathology, the appropriate management would include:

1. Re-excision to obtain clear deep margins: The involved deep margin needs to be re-excised to ensure complete removal of all tumor cells at the base. As BCCs grow downwards from the epidermis into the dermis, they must be removed fully including any extensions into the deep dermis, subcutis or other involved structures. Incomplete excision leads to higher risks of recurrence.

2. Wider margins for re-excision: For re-excision, it is recommended to take wider margins of at least 3 to 5 mm beyond the previously involved margin. As the BCC has demonstrated its ability to extend deeper than initially identified, more generous margins on re-excision help minimize the chances of remaining involved margins.

3. Select a different excision technique: For cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas of the face where tissue preservation is key, a different approach like Mohs micrographic surgery may be required for re-excision to tightly control margins while maximizing healthy tissue remaining. Mohs is also useful for poorly demarcated BCCs where surface dimensions do not accurately reflect deeper extensions.

4. Explore advanced reconstruction: If standard closure techniques will not adequately reconstruct the defect, various flap and graft procedures may need to be considered for best functional and cosmetic results following re-excision. Plastic surgery consultation is often required, especially for complex facial defects.

5. Consider adjuvant therapy: For particularly aggressive BCCs that recur despite best efforts at complete surgical removal or where further excisions carry significant morbidity, options like radiation therapy, topical 5-fluorouracil or immunomodulators may be recommended as adjuvant therapy to improve results. This helps eliminate remaining tumor cells when other approaches have maximal limits.

6. Close follow up: Patients with a BCC demonstrating deeper extension require close monitoring to ensure no recurrence develops. Follow up intervals depend on various factors but may need to be as frequent as every 3 months, especially for the first few years. Patients should be aware of the signs of potential recurrence and need to report them promptly.

Deep margin involvement indicates a more advanced BCC with a tendency to behave more aggressively, at least locally. A comprehensive approach to management including re-excision with wider margins, tissue-sparing technique like Mohs surgery where needed, advanced reconstruction options when required and judicious use of adjuvant modalities provides the best outcomes. Lifelong vigilance and sun protection minimize overall risks of new and recurrent BCCs.

Q. How to prevent recurrence of deep margin involvement during reoperation?

Several approaches can help prevent recurrence of a basal cell carcinoma with deep margin involvement during re-operation:

1. Mohs micrographic surgery: As you indicated, Mohs surgery is the ideal technique for re-excision in this setting. It provides precise margin control through frozen section analysis, allowing the surgeon to trace out the full extent of the BCC to ensure clear margins. Cure rates of up to 99% can be achieved even with aggressive, recurrent BCCs. Mohs should be considered the standard of care for recurrent BCCs, especially on cosmetically/functionally sensitive areas of the face.

2. Wider excision margins: For standard re-excision, margins of at least 3 to 5 mm beyond the previously involved margin are recommended. As the BCC has demonstrated the ability to extend deeper, more generous margins minimize the chances of unidentified outposts remaining. Wider margins may require reconstructive surgery for larger defects.

3. Different excision technique: An alternative approach like Mohs surgery may be needed when the initial technique proved unable to fully remove a deeper BCC. Mohs is highly effective for poorly demarcated tumors where clinical margins do not reflect true deeper extensions. Standard excision relies more on pre-excision margins which may be inadequate.

4. Explore underlying structures: Re-excision should explore any underlying fat, muscle, cartilage or bone to identify less obvious areas of BCC spread. Small extensions into these adjacent tissues can lead to recurrence if not addressed during re-operation. Removing underlying tissue until clear margins limits the ability of the BCC to persist.

5. Consider adjuvant treatment: For very aggressive BCCs where further excisions are not feasible or carry high morbidity, adjuvant radiation therapy, topical 5-fluorouracil or immunomodulators may be recommended. These modalities eliminate remaining tumor cells when surgery alone cannot fully achieve clearance. They improve results, especially in cosmetically sensitive areas where sacrificing additional tissue needs to be minimized.

6. Close follow up: Even with the most advanced techniques, recurrent BCCs require vigilant long term monitoring to detect any new recurrence early. Follow up at 3 to 6 month intervals, at least for the initial 1 to 2 years, is strongly advised. Prompt reporting of concerning lesions by educated patients also allows for treatment at the earliest stages.

A combination of wider and deeper re-excision using tissue-sparing Mohs surgery where possible, alternative reconstruction techniques for larger defects, judicious use of adjuvant modalities when needed and frequent long term follow up offers the most comprehensive approach to managing recurrent BCCs with deep margin involvement. Prevention of new primary BCCs through sun protection and self-examination remains ke

Q. Skin graft placed for pt and subsequently had graft failure,Cause ? Common organism?

Graft failure after skin graft placement can occur for several reasons:

1. Wound infection: As you indicated, infection is a common cause of graft failure. The most likely organisms are Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and beta-hemolytic Streptococcus. Infection disrupts the delicate inosculation and revascularization process, preventing the graft from adhering and receiving adequate blood flow. Antibiotics and repeat grafting are typically required once the infection has resolved.

2. Fluid collection (hematoma/seroma): Accumulation of blood, serum or lymph fluid between the graft and the wound bed creates a potential space, preventing adherence. Drains, pressure dressings and taping may help prevent fluid buildup. Any fluid collections must be evacuated to maximize graft take.

3. Poor graft bed: For the graft to survive, it must meet with a well-vascularized wound bed. Fat necrosis, foreign material, bone or tendon exposure will not support a split-thickness graft. Wound bed preparation or flap coverage may be needed before repeating a graft.

4. Immobility: Skin grafts require absolute immobility during the critical inosculation phase, typically the first 3 to 5 days. Any shearing forces or movement at this time will disrupt graft adherence and blood vessel connections. Strict immobilization of the affected area must be maintained with splints, casts or other devices.

5. Inadequate initial take: Partial or marginal graft failure may leave portions that never fully adhered, remaining at risk of complete failure even once past the initial critical period. Repeat grafting of non-adhered areas or other intervention may be required within the first 1 to 2 weeks.

6. Poor patient compliance: Patient factors like heavy smoking, poor nutrition, chronic edema or unreliable follow up care will negatively impact the delicate grafting process and related aftercare. Compliance with smoking cessation, limb elevation, compression and monitoring is essential to success.

7. Technical error: Imprecise graft sizing, uneven skin-graft thickness, excessively thick grafts, or improper tie-over bolstering may all contribute to technical failure of a graft. Meticulous surgical technique is important for optimal outcomes.

Addressing causative factors such as infection, fluid collections, wound bed issues, immobility and technical problems where possible, along with optimizing patient health and compliance, provide the best conditions for repeat graft success after initial failure. With appropriate intervention, the majority of graft losses can be successfully treated with a second procedure. Prevention of complications is always preferable to managing graft failure when possible.

Q. How to manage this pt with MRSA wound infection ?

Management of a patient with MRSA wound infection would include:

1. Incision and drainage of any abscesses: Drainage of pus collections is critical. Delay allows extension into deeper tissues and risks systemic spread. I&D provides material for repeat culture and sensitivity to guide antibiotic therapy.

2. Antibiotic therapy:

– For outpatients with limited infection:

•Oral options: Clindamycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, or a combination of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid.

Linezolid can also be used but is costlier.

*Daptomycin has been used for complicated MRSA but has limited oral availability and side effects.

– For hospitalized patients or severe/extensive infections:

•IV Vancomycin: Target trough levels 7-14mg/L. Usually 2-4 weeks duration.

•Linezolid 600mg IV BD. Often 10-14 day course. Useful if vanc contraindicated.

•Other IV options include telavancin, ceftaroline, ticropen/clavulonic acid. Limited data but may be alternatives.

– Decolonization:

•Nasal mupirocin BD x 5 days, OR chlorhexidine washes for full body.

•To decrease risk of auto-infection and environmental contamination.

3. Wound care:

•Debridement of necrotic tissue.

•Saline/antimicrobial washes.

•Consider VAC therapy for complex/chronic wounds.

•Repeat cultures to ensure resolution of MRSA.

4. Isolate patient:

•Contact and droplet precautions.

•Dedicated equipment.

•Cohorted staff.

•Environmental cleaning with sporicidal disinfectant.

5. Identify source:

•Obtain culture history and consider hospital screening.

•Treat any identified MRSA carriers to prevent re-infection.

The approach combines antibiotic therapy targeted to sensitivity results with drainage of infected fluid collections, meticulous wound care, infection control practices to limit spread and identification of potential sources. Eradication of carriage may also be needed. Close monitoring to ensure resolution of infection before ending precautions avoids flare-ups or spread to other patients. Recurrent MRSA infections may require repeat decolonization.

Q.After exicision , the patient developed regional LN . FNAC revealed (lymphocytes, PMNL, Histocytes, cells with an biloped nuclei) ?

The findings you describe are consistent with involvement of regional lymph nodes by Hodgkin lymphoma:

1. Reed-Sternberg cells: The cells with bilobed nuclei and “owl eye” appearance are characteristic Reed-Sternberg cells, the hallmark of Hodgkin lymphoma. Their presence confirms the diagnosis.

2. PMNLs and histiocytes: The inflammatory background in the lymph node aspiration consisting of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and histiocytes is typical for Hodgkin lymphoma. This inflammatory infiltrate surrounds the Reed-Sternberg cells.

3. Lymphocytes: Reactive lymphocytes are also commonly seen in Hodgkin lymphoma and reflect an immune response to the tumor cells. The lymph nodes often show progression from reactive lymphoid hyperplasia to effacement of nodal architecture by the tumor and inflammatory infiltrate.

4. Regional lymphadenopathy: Enlargement of regional lymph nodes is often the presenting finding in Hodgkin lymphoma. The nodes are usually non-tender but firm to hard in consistency. Hodgkin lymphoma frequently spreads in a orderly fashion from one nodal group to the next.

5. Age and gender: The age and gender of the patient also provide supportive evidence. Hodgkin lymphoma classically presents in teenagers and young adults, and also shows a slight male predominance overall in incidence.

The fine needle aspiration cytology showing Reed-Sternberg cells, surrounding inflammatory infiltrate including eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells, and the clinical finding of localized progressive lymphadenopathy in a young male patient are essentially pathognomonic of Hodgkin lymphoma, likely of the classical variety.

Staging workup including computed tomography scanning and bone marrow biopsy provide additional information on disease spread and the stage is assigned according to the Ann Arbor system. Treatment is then tailored to the disease stage and may include chemotherapy, radiation and immunotherapy for optimal outcomes.

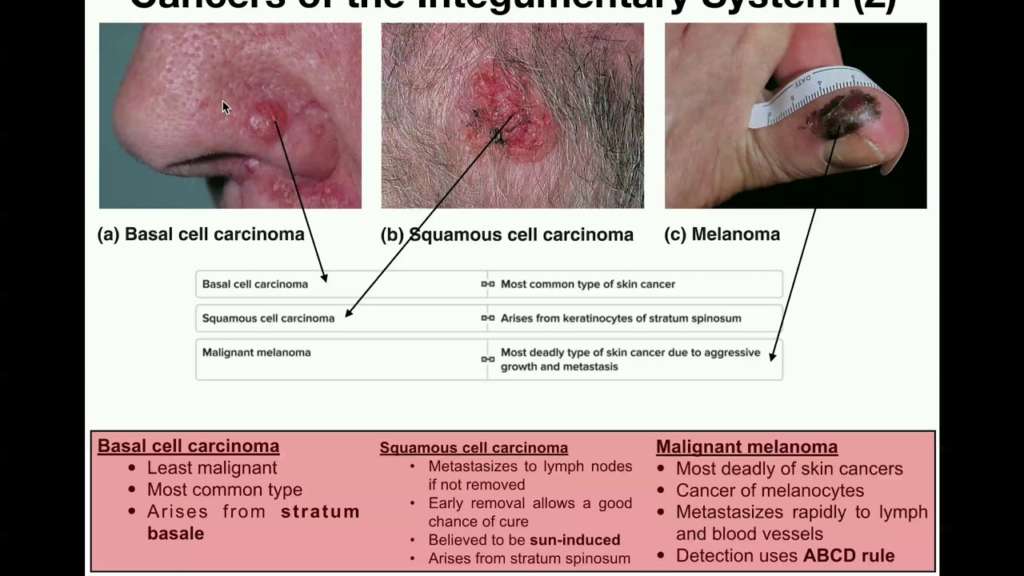

Q. What is a melanoma?

Melanoma is a malignant tumor of melanocytes, the cells that produce melanin pigment. Key features of melanoma include:

1. Origin from melanocytes: Melanocytes are found predominantly in the skin, but also in the nasal passages, eye (retina), and mucosal surfaces like the GI tract. Melanomas can arise in any of these areas, though cutaneous melanoma is by far the most common.

2. Malignant tumor: Melanomas are malignant cancers that grow in uncontrolled fashion and can metastasize if not detected early. While less common than basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas, melanoma accounts for the vast majority of skin cancer-related deaths due to its aggressive nature.

3. Association with sun/UV exposure: Excessive sun exposure and tanning bed use are major risk factors for most melanomas. Cumulative UV radiation causes DNA damage resulting in mutations that transform normal melanocytes into melanoma cells.

4. Varied clinical presentations: Melanomas can present as new or changing moles, but can also appear as non-pigmented red lesions, lumps under the skin, etc. The classic ABCDE criteria (Asymmetry, irregular Borders, multiple Colors, large Diameter, Evolution of the lesion) aid in identification.

5. Prognosis based on stage: The staging of melanoma at diagnosis is the most important factor determining prognosis. Thinner lesions limited to the epidermis (in situ) or early dermal invasion have cure rates over 95% with excision. Spread to lymph nodes or distant organs (Stage III/IV) carries higher mortality risks despite aggressive treatment.

6. Treatment options: Early stage melanomas are treated by wide local excision of the primary lesion. Sentinel node biopsy assesses nodal spread. Advanced disease requires lymphadenectomy, systemic therapies like immunotherapy or chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. Newer targeted and immunologic agents are improving outcomes, especially for metastatic melanoma.

In summary, melanoma is a potentially aggressive malignant tumor of melanocytes that arises most often from sun-damaged skin. Prevention through UV avoidance and protection along with early detection of concerning lesions offers the best outcomes. Multidisciplinary management is required, and treatment options range from surgery alone for early lesions to systemic therapy for advanced disease. Ongoing research continues to improve prognosis, especially for higher stage melanomas

Q. How is diff from SCC ?

The key differences include:

1. Cell of origin: Melanoma arises from melanocytes located in the stratum basale, the deepest layer of the epidermis. SCC arises from keratinocytes in more superficial layers, especially the stratum spinosum.

2. Etiology: Melanoma is linked to intermittent sun/UV exposure, especially sunburns. SCC is associated more with chronic long-term sun exposure.

3. Age and location: Melanoma can occur in younger individuals and on any skin surface. SCC primarily affects older individuals and sun-exposed sites.

4. Appearance: Melanoma presents as an asymmetric, irregular, multi-colored mole. SCC presents as a red, scaly patch or non-healing ulcer, often with keratin debris.

5. Incidence: Melanoma accounts for only about 4% of skin cancers but the vast majority of skin cancer deaths. SCC is over 4 times more common, accounting for about 16% of skin cancers.

6. Metastasis: Melanoma frequently spreads to distant sites like lymph nodes, lungs, brain, etc. SCC only rarely metastasizes, remaining confined to local and regional tissues.

7. Treatment: Melanoma often requires surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy and radiation. SCC is usually managed by surgical excision alone with good outcomes.

8. Prognosis: Melanoma has a poorer prognosis, especially for advanced stages. SCC has a very favorable prognosis when detected and removed early.

In summary, while SCC and melanoma are the two most common skin cancers, they differ in almost every aspect from cellular origin to treatment and prognosis. Understanding these differences is key to early detection and appropriate management. Both benefit most from prevention – limiting UV radiation exposure and sun protection from an early age.

Q. Biopsy report, what would you like to know, and what else do you need to know?

Key features I would want to know from a melanoma biopsy report include:

Essential features:

1. Breslow thickness: The thickness of the melanoma in mm. The most important prognostic factor determining risk of metastasis and survival. Thinner lesions have better outcomes.

2. Ulceration: Present or absent. Ulcerated melanomas have worse prognosis.

3. Mitotic rate: Number of mitoses per mm2. Higher mitotic rate indicates more aggressive tumor and poorer prognosis.

Other important features:

1. Histologic subtype: Superficial spreading, nodular, lentigo maligna, acral lentiginous, etc. Nodular and acral lentiginous subtypes tend to be more aggressive.

2. Vascular/lymphatic invasion: Present or absent. Indicates higher risk of metastasis if present.

3. Margins: Clear or involved. Clear margins (no tumor cells at peripheral and deep margin) are required for optimal excision and cure.

4. Anatomic level (Clark level): Indicates how deeply the melanoma extends into the layers of the skin. Higher levels (IV-V) have worse prognosis.

5. Regression: Indicates areas where melanoma cells have been destroyed by the immune system. Can make assessment of thickness and margins difficult.

6. Microsatellitosis: Small aggregates of melanoma cells in the dermis adjacent to the main tumor mass. An adverse feature indicating higher risk of metastasis.

7. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes: Brisk lymphocytic reaction surrounding the tumor. Can indicate a more favorable host response to the melanoma.

8. Vertical growth phase: When melanoma acquires ability to invade into deeper dermis and beyond. Required for metastasis to occur and sign of more advanced tumor.

Additional workup required would include:

– Full body skin exam to check for other suspicious moles

– Sentinel lymph node biopsy to stage nodal involvement

– CT/PET scans if indications of aggressive or advanced melanoma

– Genetic testing on tumor tissue especially for newer targeted therapies

The biopsy report provides crucial information to determine proper staging, prognosis and treatment for a melanoma. Wide local excision and possible lymph node surgery is required at a minimum, but additional interventions may be needed for high-risk and advanced melanomas. Lifelong follow up is essential even after successful initial treatment.

Q. 1mm MM, margins & < 1 MM during procedure, what would you do next?

For a melanoma with a Breslow thickness of 1 mm and margins less than 1 mm on initial excision, I would recommend:

1. Wider local excision: As you indicated, the most important next step is to re-excise the site of the initial excision to obtain clear margins of at least 1 cm of normal tissue circumferentially around the scar. For melanomas 1 mm or less in thickness, 1 cm margins are typically recommended. This helps ensure complete excision minimizing risk of local recurrence.

2. Consider sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB): For melanomas between 1 to 2 mm thickness, SLNB provides important staging information and may detect microscopic nodal involvement even when the nodes appear normal clinically. A positive SLNB would indicate the need for complete lymph node dissection. SLNB can be done at the time of re-excision or as a separate procedure.

3. Follow up and monitoring: Following re-excision, the patient should be followed closely with:

– Full body skin exams: To detect any new or concerning moles. Melanoma survivors are at higher risk of developing another primary melanoma.

– Lymph node exams: Even if SLNB negative, there is still a small risk of delayed nodal metastasis over time. Nodes should be checked at each visit.

– Imaging: For very thin melanomas, routine imaging like CT/PET scans are not indicated unless symptoms occur concerning for distant spread. They should remain part of follow up for life, however.

– Frequency: Visits every 3 to 6 months for the first 2-3 years, then 6 to 12 months for the next 2 years, and at a minimum annually lifelong. Early detection of any recurrence is critical.

4. Patient education: Educate the patient on prevention with regular self-exams, sun protection and avoidance of tanning beds. Also teach them the signs of possible recurrence to look out for between visits like new lumps, skin changes, or unexplained symptoms. Early reporting of concerning signs is important.

5. Consider adjuvant therapy trials: For very early but high-risk melanomas like yours, there are some clinical trials on interferon alfa or other immunologic agents to reduce risks of recurrence. Participation in an adjuvant therapy trial could be discussed.

With close monitoring and proper management following re-excision, the prognosis for melanomas around 1 mm thickness that have not ulcerated remains very good. However, lifelong care is required given the potential for late recurrence and new primary melanomas. Prevention and education offer the best outcomes with early detection of any new or concerning disease.

Q. Lesion excised Breslow thickness 1.5mm, margins 0.5cm what to do?

For a melanoma with a Breslow thickness of 1.5 mm and margins of 0.5 cm, the following steps would be recommended:

1. Re-excise to obtain 2 cm margins: As you noted, for melanomas between 1 to 4 mm in thickness, margins of 1 to 2 cm are recommended. Given the inadequate 0.5 cm margins on initial excision, re-excision to obtain clean 2 cm margins of normal tissue around the scar should be performed to minimize risk of local recurrence.

2. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB): For a melanoma of 1.5 mm thickness, SLNB is indicated to stage the nodal basin and check for any microscopic metastasis. If SLNB is positive, complete lymph node dissection would be required. Even with a negative SLNB, life long nodal monitoring will be needed.

3. Close follow up: After re-excision and any required nodal surgery, close follow up and monitoring would consist of:

– Skin exams every 3 months for 2 years, then every 4 to 6 months for 3 years. Lifelong annual skin checks recommended.

– Nodal exams at each visit even if SLNB is negative. Up to 10-15% risk of false negative SLNB, so delayed nodal recurrence is possible.

– Routine CT/PET imaging not usually needed initially but may be used for concerning signs/symptoms. Remain part of lifelong follow up.

– Educate patient on prevention, self-examination and signs of recurrence which warrant urgent evaluation. Early reporting critical.

4. Consider adjuvant therapy: For melanomas 1.5 mm or greater, especially if ulcerated, there is data to support use of 1 year of high-dose interferon alfa to reduce recurrence risks. This or other immunotherapy/targeted agents could be discussed, especially as part of a clinical trial.

5. Genetic testing: Tumor tissue may be tested for specific mutations like BRAF to guide follow up as well as potential use of targeted therapies if recurrence develops.

With appropriate re-excision, nodal staging, close monitoring and education, the prognosis for a 1.5 mm melanoma that has not ulcerated remains good, with over 90% long term survival. However, risks of recurrence or new primary melanomas remain life long, so ongoing care and self-examination are essential for optimal outcomes. Adjuvant therapy may further improve prognosis for some patients in this range, and should be considered where appropriate based on features like ulceration, high mitotic rate, etc.

Q. How to do this intraoperatively?

Intraoperative analysis of excision margins during melanoma surgery can be done using:

1. Frozen section evaluation: This involves taking representative tissue samples from the margins of excision and rapidly freezing and sectioning them to obtain slides for microscopic analysis by a pathologist. The pathologist can examine the slides and provide a preliminary report on margin status before closing the incision.

– Pros: Allows for immediate re-excision of positive margins. Ensures clear margins before ending procedure.

– Cons: Only samples some parts of margin, could miss a positive area. Adds time, complexity and cost to procedure.

2. Mohs surgery: The excised specimen is divided into sections that are mapped to their location. Sections from periphery and deep margin are processed and stained as frozen sections while patient waits. The surgeon uses the path report to guide excision of additional sections from any areas positive until all margins clear.

– Pros: Allows complete margin analysis and highest cure rate. Maximizes preservation of normal tissue.

– Cons: Most time-consuming, complex and expensive option. Requires Mohs-trained surgeons and pathologists.

3. Rush permanent sections: The specimen is sent for accelerated processing of margins using permanent sections, with a faster staining turnaround time. The path report on full margin status may return within 30 to 60 minutes to allow re-excision if needed.

– Pros: Evaluates 100% of margins with accuracy of permanent sections. Reasonably timed for intraoperative use.

– Cons: Still can require patient to wait under anesthesia for up to an hour. Not all centers may have capability for accelerated permanent section processing.

For any intraoperative technique used, the patient will be kept under anesthesia during the time required for pathologic processing and review of margin status. Re-excision of positive margins may require taking additional normal tissue around the entire previous excision site. The ideal option balances maximizing margin evaluation with feasibility, cost and patient safety.

In the end, close follow up and monitoring after any melanoma excision is still needed to detect recurrences without symptoms, even when the initial margins were deemed to be clear. However, intraoperative assessment of margins and re-excision to obtain clear margins where indicated provides the optimal starting point for any melanoma. Mohs or permanent section rush evaluation may be preferred when margins will be difficult to assess or on cosmetically sensitive areas of the head and neck. A multi-disciplinary approach will determine the ideal technique based on each individual patient and tumor.

Q. Gene responsible for familial MM?

You are correct, there are several genes that have been implicated in familial melanoma. The major genes include:

1. CDKN2A: This is the most commonly mutated gene in melanoma-prone families. It encodes two proteins, p16INK4A and p14ARF, that are tumor suppressors. Mutations in CDKN2A can be detected in 20-50% of melanoma families with 3 or more affected members.

2. CDK4: This is the second most commonly mutated gene, with mutations identified in about 5-20% of high-risk melanoma families. It encodes a cyclin-dependent kinase that regulates cell cycle progression. Mutations prevent normal regulation of CDK4, allowing uncontrolled cell growth.

3. MC1R: Variants of this gene are strongly associated with red hair, freckles and increased sun sensitivity. Certain inherited MC1R variants also increase melanoma risk 2 to 3 fold. However, MC1R variants alone do not seem to cause highly penetrant familial melanoma. Other genes like CDKN2A are often also mutated.

4. BRCA2: While best known as a breast cancer susceptibility gene, BRCA2 mutations have also been linked to increased melanoma risk. Rare families with BRCA2 mutations may exhibit occurrence of both breast cancer and melanoma.

5. Other genes: Additional genes found to be mutated in a small subset of melanoma families include MITF, POT1, TERF2IP, ACD, and CASP8. However, their role in familial melanoma risk seems to be less well-defined.

Gene mutation testing can be helpful for familial melanoma in several ways:

1. Diagnosis: Identifying a known pathogenic mutation in a gene like CDKN2A or CDK4 confirms a genetic predisposition to melanoma in the family.

2. Screening: Family members can be tested for the same mutation to identify those also at high risk who require intensive screening.

3. Risk assessment: The specific gene and type of mutation can help determine approximate lifetime melanoma risk for mutation carriers.

4. Prevention: Knowing mutation status helps guide counseling and prevention strategies for high-risk individuals like frequent skin checks, sun protection and avoiding tanning beds.

5. Treatment: In the future, gene status may guide eligibility for newer targeted therapy options and immunotherapy clinical trials.

Genetic testing for melanoma should be considered for any family with 3 or more affected members over multiple generations. Identifying the underlying mutation and which family members carry it empowers high-risk individuals and their doctors to take appropriate action for prevention and early detection of melanoma.

Q. Poor prognostic factors?

Poor prognostic factors for melanoma include:

1. Male gender: Melanoma tends to be more aggressive in men compared to women, after controlling for other factors. Men tend to have worse survival rates at each stage of melanoma.

2. Increasing age: As with most cancers, melanoma survival rates decrease with advancing age at diagnosis. Elderly patients tend to have worse outcomes partly due to more advanced stage at diagnosis and higher rates of comorbid conditions.

3. Ulceration: The presence of ulceration in the primary melanoma tumor is one of the most significant adverse prognostic factors. Ulcerated melanomas have much higher risks of metastasis and poorer survival.

4. Site: Melanomas arising on the lower leg (especially distal), scalp/neck, and trunk have a worse prognosis compared to upper extremity lesions. These sites are associated with higher Breslow thickness at diagnosis and more aggressive tumor biology.

5. Breslow thickness: Increasing thickness of the melanoma correlates strongly with higher stage, greater risk of metastasis and poorer outcomes. Thicker lesions are more advanced and difficult to treat.

6. Mitotic rate: A higher mitotic rate, indicating more rapid cell turnover and division, predicts worse prognosis. It is incorporated into the pathological staging system for melanoma.

7. Metastasis: The development of distant metastasis to organs like lungs, liver or brain significantly worsens prognosis. The location and number of metastasis also affect expected survival.

8. Recurrence: Patients experiencing a local, regional or distant recurrence of melanoma have a poorer prognosis compared to those with no recurrence after initial treatment. Recurrent disease is often more difficult to cure.

9. Immunosuppression: Individuals with impaired immunity, whether iatrogenic (organ transplant patients), inflammatory (lupus, IBD) or infectious (HIV), tend to develop thicker, higher stage melanomas with lower survival rates. Immunocompromise is considered an independent poor prognostic factor.

While factors like age, site and Breslow thickness at diagnosis cannot be altered, close surveillance of high-risk patients and early treatment offer the opportunity to diagnose melanoma at an initial stage when outcomes can still be excellent. Avoiding excessive sun exposure and tanning also helps preclude the development of melanoma in the first place. Advances in treatment offer hope even in those with poor prognostic factors. A multi-disciplinary team approach is critical for optimum management of these patients.

Q.What skin condition is associated with melanoma?

several conditions associated with an increased risk of melanoma:

1. Xeroderma pigmentosum: This rare inherited disorder results in a deficiency of DNA repair from ultraviolet radiation damage. It causes severe sun sensitivity and a greatly increased risk of skin cancers, including melanoma. Regular skin surveillance is required from an early age.

2. Albinism: Lack of skin pigmentation causes increased transparency to UV light and melanoma risk. Melanin helps protect skin cells from sun damage, so its absence provides less inherent protection. Diligent sun protection and monitoring are essential for these patients.

3. Congenital giant pigmented nevi: Large congenital moles, especially if greater than 20 cm, carry a higher risk of becoming malignant or being associated with melanoma. Complete surgical excision is often recommended, when feasible, to remove melanoma risk. Close monitoring of any remnants or incompletely excised nevi is required.

4. Fair skin (Fitzpatrick type 1): Very fair skin that never tans and always burns in moderate sun exposure (FST 1) lacks protective pigmentation. This skin type faces the highest risk of sun damage and melanoma, demanding conscientious photoprotection and sun avoidance.

5. Dysplastic nevi and high nevus count: The presence of dysplastic or atypical moles, and a large total number of moles or nevi, are markers of increased genetic predisposition to melanoma. These individuals warrant regular full body skin exams, self-monitoring for new or changing moles, and photography to detect troublesome lesions early.

6. Previous non-melanoma skin cancer: A patient with a past history of basal or squamous cell carcinoma is at higher risk of also developing melanoma. Ongoing surveillance by a dermatologist is recommended even after treatment of non-melanoma skin cancers.

7. Certain HPV/HIV infections: Infections like certain high-risk HPV strains and untreated HIV can promote skin carcinogenesis including melanoma. Managing infections when present and regular skin checks are important for early diagnosis.

The conditions you noted, especially in combination, identify individuals who would benefit most from targeted melanoma prevention, education and close monitoring. Early detection of cancerous changes offers the best prognosis. Photoprotection, mole mapping, and self-examination should start at an early age in high-risk groups. A proactive multidisciplinary approach to management can optimize outcomes even among those facing the highest risks of disease.

Q. General principles of melanoma excision surgery?

The general principles for surgical excision of melanoma include:

1. Obtain clear margins: The most important goal is to remove the entire melanoma tumor along with a margin of normal surrounding tissue. For in situ melanoma, 0.5 cm margins are typically recommended. For invasive melanoma, 1 cm margins for Breslow depth under 1 mm, 1-2 cm for 1-4 mm, and 2 cm for over 4 mm are common guidelines based on thickness. Wider excision may be required if lines of excision are difficult to determine histologically.

2. Depth of excision: The excision should extend through the subcutaneous fat layer beneath the dermis and melanoma. Fascia and muscle typically do not need to be removed. The goal is to remove any potential microscopic extensions of melanoma cells beyond what is visible clinically.

3. Orientation: The excised specimen should be oriented for pathologic analysis by marking with sutures or clips so if closer margins are needed, the pathologist and surgeon know the location of any positive margins for re-excision. Photographs before excision can also aid orientation.

4. Closure: The wound after wide local excision of melanoma will require layered closure for adequate healing and cosmesis. Options include primary closure, skin grafts, or skin flaps based on the size of excision. Healing by secondary intention is avoided.

5. Lymph node evaluation: For higher risk melanomas, especially over 1 mm thickness, sentinel lymph node biopsy is often recommended to evaluate the regional nodal basin for any microscopic spread. Positive sentinel nodes may require complete lymph node dissection. Node dissection can be done at the same time as wide excision or as a separate subsequent procedure.

6. Follow up: Close follow up with both the dermatologist and surgical oncologist is needed after melanoma excision to monitor for recurrence. Skin exams, nodal assessments, imaging and testing for systemic spread may be part of follow up, especially for higher stage lesions. Patient education on prevention and self-examination is also critical.

7. Consider reconstruction: For melanomas excised from cosmetically sensitive areas like the face, reconstruction done by a plastic surgeon may be needed to optimize both function and appearance. Timing of any reconstruction depends on need for adjuvant radiation or nodal surgeries.

With proper surgical management, the majority of melanoma tumors can be successfully eradicated. However, lifelong monitoring for local or distant recurrence, new primary lesions, and encouraging strong prevention behaviors among patients remain equally as important for overall outcomes. A coordinated multidisciplinary approach among surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, dermatologists and pathologists offers the highest quality patient care.

Q. If go for re-excision, what to do to ensure adequate margins this time round?

To ensure adequate clear margins when re-excising a melanoma, several techniques can be used:

1. Mohs micrographic surgery: This specialized technique uses total circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment with frozen section analysis to guide sequential excision until clear margins are obtained. It provides the highest rate of complete excision but requires a trained Mohs surgeon and pathologist, and can be time consuming. It is often used for melanomas in cosmetically sensitive areas like the face.

2. Permanent section rush evaluation: Excising wider margins, the excised specimen is evaluated with accelerated processing of permanent pathology sections, with results in 30 to 60 minutes. The pathologist assesses the full circumferential and deep margins, and if any are still positive, indicates areas for re-excision. This also provides complete margin evaluation with high accuracy but may require longer time under anesthesia awaiting final path results.

3. Frozen section margin assessment: Representative sections from the peripheral and deep margins are evaluated by frozen section. If any margins are positive, wider re-excision is performed. However, frozen sections only sample certain portions of the margins, so could potentially miss some areas of residual tumor. Often used when permanent section rush evaluation is not available.

4. Wider re-excision without intraoperative margin analysis: Simply re-excising a wider area around the entire previous scar, for example >2 cm margins, and then relying on assessment of the re-excised permanent pathology sections to determine if margins are clear. No analysis of margins is done during surgery. This wider “blind” re-excision aims to increase chances of obtaining clear margins but risks removing more normal tissue than needed. Permanent margin status not known until final path results return in several days.

5. Consider radiation therapy: For some melanomas, especially on cosmetically sensitive areas where extensive surgery risks significant deformity or loss of function, radiation therapy may be used when margins remain persistently positive. Radiation is often used as an adjunct to surgery when re-excision is not possible. Strict radiation protocols for melanoma must be followed.

For any re-excision, careful orientation of the specimen during surgery and measurements of all margins and dimensions are critical to allow accurate assessment and localization of any residual positive margins by pathology. Photography and mapping prior to initial excision also aid proper orientation for the pathologist. Complete circumferential and deep margin evaluation using Mohs, permanent section rush analysis or frozen sections provides the highest chance of achieving clear margins during a single re-excision. However, when margins will be difficult to assess or in cosmetically sensitive areas, Mohs micrographic surgery is considered the gold standard management technique.

Q.Post axillary clearance complained of arm pain and swelling (axillary vein thrombosis)…Risk factors for thrombosis? (Virchow’s triad)?

This patient’s arm pain and swelling after axillary lymph node dissection suggests the possibility of axillary vein thrombosis, which can be a complication of this procedure. The major risk factors for thrombosis are summarized by Virchow’s triad:

1. Hypercoagulability: Cancer and its treatments can increase clotting factors and platelets, promoting a pro-thrombotic state. This patient’s melanoma and axillary surgery would increase risk.

2. Stasis of blood flow: Disruption of normal blood flow patterns and venous return from the arm after lymph node surgery may lead to localized stasis, slowing flow through vessels like the axillary vein.

3. Vessel wall injury: Any damage to the inner lining of the axillary vein during surgery provides a surface for clots to form. Clotting factors interact with the exposed subendothelial collagens of the vein wall.

Additional risk factors for this patient include:

– Postoperative immobilization: Lack of movement following surgery further slows venous return and blood flow from the arm, promoting stasis. Early ambulation and arm mobility are encouraged but may still be limited after axillary dissection.

– Indwelling catheters: IVs and drains placed during and after the procedure can also trigger clot formation or vessel wall damage. Proper line/drain care and timely removal reduces risks.

– Smoking: Tobacco use increases risks of hypercoagulability and poor wound healing, and is considered an independent risk factor for thrombosis. Patients should avoid smoking, especially around the time of surgery.

To diagnose axillary vein thrombosis, tests like duplex ultrasonography, CT or MRI venography may be used. Treatment typically involves anticoagulation with heparin followed by 3 to 6 months of warfarin therapy. For persistent symptoms, thrombolysis or thrombectomy may be required to break up or remove the clot.

Modalities to potentially prevent axillary vein thrombosis include:

-early ambulation and arm range-of-motion: when possible after surgery

-compression sleeves/bandages: to reduce swelling and improve flow

-anticoagulation: prophylactic low molecular weight heparin and/or aspirin may be used

-minimize vein damage: Careful and limited dissection around the axillary vein during lymph node surgery

-IV placement: Avoid multiple IV attempts and promptly remove any lines no longer in use

-Preoperative smoking cessation: Avoiding smoking for at least 4 weeks before and after surgery

Skin bruising, pain, swelling or redness in the arm, or new upper extremity dysfunction up to several weeks after axillary dissection warrant evaluation to exclude axillary vein thrombosis or other procedure-related complication which would require prompt management to prevent long term sequelae. Early recognition and treatment of post-surgical clots is critical for optimum outcomes.

Q. How to differentially diagnose?

1. Clinical assessment: Carefully evaluate the location, size, temperature, tenderness of the axillary swelling. A DVT may be warm, painful, lumpy along the course of veins. Lymphedema tends to be spongy, non-tender, involves the subcutaneous tissues. Hematoma is often tense, tender, and bruised overlying the surgical site. Correlate with time since surgery and other symptoms.

2. Ultrasound guided FNAC: Perform FNAC under ultrasound guidance to ensure correct placement of needle in the area of concern. Blind aspiration risks injury and non-diagnostic samples.

3. Check for blood flow: Gently pull back on the syringe plunger with needle in place to check for any blood flow or the presence of clotted blood. Free flow or minimal clotting makes DVT very unlikely. No blood aspiration suggests lymphedema or other fluid.

4. Analyze fluid color and consistency: Blood from a patent vein or hematoma will be bright red and flow freely. Older clotted blood has a darker, maroon color with cheeze-like or jelly-like consistency. Lymphedema yields clear or yellow tinged watery or slightly viscous fluid. Purulent fluid suggests infection.

5. Look for venous endothelial cells: Spin down any fluid or blood obtained and analyze under the microscope. Intact venous endothelial cells are seen with axillary vein FNAC, but will not appear in lymphedema fluid. Endothelial cells may also appear distorted or damaged if there is thrombosis present.

6. Additional stains if needed: Deeper analysis of any tissue fragments or cells obtained can be done with stains like Gram stain (to detect bacteria), fluid chemistry (to assess lactate dehydrogenase, albumin, protein), cell block or core biopsy. These provide more detailed analysis to determine an accurate diagnosis.

Q. Had extensive surgery for axillary lump, presented with red swollen upper extremity, what are possibilities?

After extensive axillary surgery, several possibilities could cause redness, swelling and pain of the upper extremity:

1. Hematoma: Blood collecting under the skin from damage to small blood vessels during surgery. Usually appears soon after surgery, tense, and painful. Resorbs over time but may require drainage if large.

2. Seroma: Clear fluid collecting in the space left after lymph node removal. Also from surgical disruption and inflammation. Feels like a water balloon. Often drains on its own but multiple needle aspirations or drain placement may be needed.

3. Superficial thrombophlebitis: Inflammation of superficial veins causing pain, redness and tenderness along the vein track. From venous stasis or damage. Rarely dangerous but painful. Compression, elevation, warm compresses and NSAIDs provide relief as it resolves over weeks.

4. Deep vein thrombosis: Clot forming in deeper veins, like the axillary vein. Swelling is hard, painful and unilateral. Risks include pulmonary embolism so anticoagulation is needed. Diagnosis by ultrasound or CT and bloodwork.

5. Lymphedema: Swelling from impaired lymphatic drainage. Develops slowly over weeks and months. Non-tender, spongy and involves the subcutaneous tissues with pitting edema. Requires lymphatic massage, compression and exercise. Chronic condition managed long term.

6. Surgical site infection: Uncommon but serious possibility presenting with increasing pain, redness, swelling and pus at the incision site. Needs prompt diagnosis by culture and treatment with antibiotics, possible incision and drainage.

Diagnosis is made through clinical assessment of characteristics like rapidity of onset, location, consistency and temperature of swelling, associated symptoms, as well as any recent radiation or trauma. Doppler ultrasound, CT, bloodwork and possible needle aspiration or culture may be required in some cases. Time since surgery, operative procedure details, current medications and co-morbid conditions also provide important clues to the correct diagnosis.

Prompt management of hematoma, seroma or infection is needed to prevent complications and aid recovery. DVT requires urgent treatment to minimize risks like pulmonary embolism. Thrombophlebitis and lymphedema develop slowly with treatment aimed at symptom relief and preventing recurrence. Close follow up after any extensive axillary surgery is mandatory to monitor for changes that could indicate problems and allow early diagnosis and intervention.

Q.How to treat DVT ?

Key treatments for deep vein thrombosis well:

1. Anticoagulation: This is the mainstay of DVT treatment. Initial acute anticoagulation starts with parenteral agents like low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), fondaparinux or intravenous unfractionated heparin to inhibit further clot propagation. Longer term anticoagulation for at least 3-6 months is with warfarin to a target INR of 2-3. Rivaroxaban and apixaban are direct oral anticoagulants also used for longer term treatment.

2. Catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT): For extensive clots causing phlegmasia or threatening venous outflow, CDT uses a catheter to deliver clot-busting drugs directly into the thrombus. Drugs like alteplase are infused over hours to days. This works best within 14 days of symptom onset before clots become organized. Fibrinogen levels must be monitored to avoid hemorrhage. CDT patients also continue anticoagulation long term.

3. Vena cava filter: For patients who cannot be anticoagulated or at high risk of pulmonary embolism, an inferior vena cava filter can be placed to prevent large clots from reaching the lungs. Filters do not treat existing DVT but prevent life-threatening PE. Retrievable filters should be removed once anticoagulation is safe and to avoid long term filter complications.

4. Compression stockings and elevation: These provide symptomatic relief from edema and pain in the affected limb. Knee-high stockings with 30-40 mmHg pressure are typically used, especially in those with limited mobility and during long term air travel where DVT risk is increased.

5. Ambulation and physical therapy: Early walking and range-of-motion exercises also help prevent complications like pulmonary embolism and the post-thrombotic syndrome. Movement prevents stasis of blood flow which contributes to clot formation. Therapy may be needed for weakness from prolonged immobility during initial DVT treatment.

You’re right that treatment beyond 6 months provides little added benefit for most DVT patients in preventing recurrence. However, some cases like those with certain clotting disorders, recurrent DVT or proximal DVT may require lifelong anticoagulation therapy to manage risks. Follow up to monitor for post-thrombotic syndrome and screen for clot recurrence or extension is also needed.

In summary, prompt diagnosis and initiation of parenteral anticoagulation remain key to management of DVT. Clotting therapy, compression, mobilization and risk factor reduction can prevent both short and long term complications when applied appropriately according to each patient’s risks and needs. Aggressive CDT and filter placement are reserved for more severe and complicated thrombotic disease not amenable to standard medical management. With treatment, the majority of DVT patients recover well but require ongoing monitoring and education for this chronic condition.

Q. How to manage thromboembolism?

Management of thromboembolism includes:

1. Anticoagulation: This is the cornerstone of treatment for thromboembolism like deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE). Initial acute anticoagulation is with parental agents like heparin, low molecular weight heparin or fondaparinux. Longer term treatment is usually with warfarin. Direct oral anticoagulants like rivaroxaban or apixaban are also used.

2. Thrombolysis: For extensive, life-threatening clots causing circulatory compromise, thrombolytics like alteplase can be infused through a catheter to help break up clots. This is especially used for PE causing hemodynamic instability. Close monitoring is needed due to bleeding risks.

3. Embolectomy: Surgical removal of emboli may be used for those unable to undergo thrombolysis. A catheter is inserted to extract clots and restore blood flow. Often a last resort due to its invasiveness.

4. Vena cava filter: For those unable to be anticoagulated who are at high risk of further embolism. A filter is placed in the inferior vena cava to catch clots before they reach the lungs or heart. Not meant as definitive treatment but to prevent a potentially fatal first episode of PE in select patients.

5. Compression stockings: Help reduce swelling and prevent post-thrombotic syndrome. Graduated compression stockings also aid flow of deoxygenated blood back to the heart.

6. Lifestyle changes: Losing excess weight, staying mobile and adequately hydrated, avoiding prolonged inactivity or immobilization and eliminating smoking all help lower risk of recurrence.

Risk factors for thromboembolism include:

1. Hypercoagulability: Inherited or acquired clotting disorders; cancer; antiphospholipid syndrome; etc.

2. Stasis: Prolonged immobilization; paralysis; leg fractures; air travel; etc. Impaired flow allows clots to form.

3. Endothelial injury: Surgery; trauma; IV catheter; etc. Damage to vein walls triggers clotting.

4. Age over 60 years: Increased clotting risk with aging.

5. Obesity and smoking: They both promote inflammation, clotting and health risks.

6. Hormone use: Oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy increase estrogen which elevates clotting factors.

7. Previous DVT or PE: The highest predictor of recurrence. Up to 10% of PE survivors have another episode within 10 years without treatment.

8. Certain medical conditions: Heart failure; COPD; nephrotic syndrome; IBD; etc. They create a pro-thrombotic state through various mechanisms.

9. Hospitalization and long distance travel: Prolonged immobility associated with increased DVT risk. Travelers thrombosis occurs due to cramped positions over several hours. Anticoagulants or compression socks may help prevent.

Close follow up, anticoagulation and risk factor management are key to reducing recurrence and complications of thromboembolism. Patient education on signs and symptoms to report is also very important for early diagnosis and treatment of any new clots.

Q.What macroscopic/microscopic features of malignant melanoma lesion?

Macroscopic and microscopic features that suggest a malignant lesion include:

Macroscopic:

1. Asymmetric shape: Benign lesions are usually symmetric, round or oval. Malignant lesions have irregular, asymmetric borders.

2. Irregular borders: Jagged, raised or blurred borders suggest malignancy vs the smooth, well-defined borders of a benign lesion.

3. Varied pigmentation: Multiple shades of brown, black, red or white within the lesion are suspicious. Benign lesions tend to have uniform coloration.

4. Diameter >6mm: Though not definitive, malignant lesions often start larger or grow more rapidly than benign lesions. However, some malignant melanomas arise from smaller pre-existing nevi.

5. Ulceration or bleeding: Exposed red base, bleeding, crusting or non-healing ulcer indicate malignant potential for skin-based lesions.

6. Rapid change: Any lesion showing changes in size, shape, color, elevation or symptoms over weeks to months needs prompt biopsy to rule out cancerous changes.

Microscopic:

1. Atypical cells: Varied cell size and shape, enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and sparse cytoplasm are features of malignant cells. They show disordered, uncontrolled growth.

2. Pagetoid spread: Malignant cells spreading superficially within the epidermis, above the basal layer. This pattern of upward growth is characteristic of melanoma.

3. Lack of maturation: Malignant tumor cells do not mature and differentiate as they move deeper into the dermis like benign tumor cells or normal melanocytes. They retain undifferentiated features throughout the lesion.

4. Mitotic figures: The presence of cells actively dividing and undergoing mitosis within the dermis indicates aggressive behavior. Benign tumors show few to no mitoses, especially deeper in the dermis.

5. Sheets and nests: Diffuse masses or tightly packed aggregates of tumor cells invading the dermis signal malignancy. Benign lesions have a more orderly, structured appearance.

6. Destruction of stroma: Malignant tumors invade and destroy the collagen and stroma of the dermis as they expand. The stroma remains intact around benign lesions.

7. Lymphovascular invasion: Tumor cells penetrating into lymphatic vessels or small capillaries within the dermis strongly suggest metastatic potential, a hallmark of malignancy.

These features help determine if a lesion may be low or high risk, guiding the extent of initial biopsy and surgery required. They also provide important prognostic information to determine appropriate post-excision follow up and monitoring for both patient and physician.

Q.Histology vs. Cytology?

Histology and cytology are both techniques used to study cells and tissues, but differ in their methodology and applications:

Histology:

• Involves preparing thin tissue sections from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks that can be stained and examined under a microscope.

• Provides architectural context, allowing analysis of the relationship between cells and their surrounding stroma. Individual cell morphology can also be assessed.

• Used for initial diagnosis of tumors and other diseases as the gold standard, as well as grading and staging to determine prognosis and guide treatment.

• Requires viable cells and tissue architecture, so only possible in living or freshly dead specimens. Cannot be done on isolated cell samples or fluids.

• More technical expertise and time required to prepare slides and review, especially for complex specimens.

• Examples: Assessing margins and lymphovascular invasion from melanoma specimens, distinguishing benign from malignant skin lesions, grading and staging cancers, etc.

Cytology:

• Involves preparing and staining isolated cell samples from fluids (ascites, pleural), washings (bronchoalveolar), scrapings (Pap smear), or fine needle aspiration to analyze cell morphology and features.

• Limited to analysis of individual cell characteristics. Lacks architectural context but can provide rapid on-site evaluation and is useful where histology is not possible.

• Often used as an initial screen for malignancy or where biopsy is challenging, with subsequent histology performed for definitive diagnosis and full pathological assessment.

• Can be done on isolated cells, making it useful where only fluids, washings or limited cells can be obtained. Rapid on-site evaluation allows for re-sampling if needed.

• Usually quicker and less technically challenging to prepare and review slides compared to most histology specimens.

• Examples: Analyzing Pap smear, pleural fluid or ascites specimens for cancer cells, thyroid or lymph node FNA interpretation, etc.

In summary, while histology and cytology share some similarities in the preparation and staining of cells and tissues for microscopic examination, they differ primarily in the type of sample they analyze and the kind of information they provide. Histology examines intact tissue sections, allowing evaluation of both cell morphology as well as tissue architecture. Cytology looks at isolated cells removed from their architectural context. Both play an important role in diagnosis and management of patients.